The Early Middle Ages

advertisement

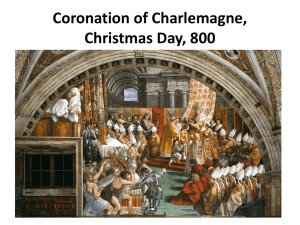

The Early Middle Ages The Middle Ages is so named because it fell between two great periods and two significant events: the Roman Empire marked by the fall of Rome and the Early Modern Period marked by Columbus’s discovery of America. By the 7th century, the world of Pax Romana had split into three separate areas: Western Europe (Britain, Gaul, Germany, and Italy), Byzantium (Greece and Asia Minor), and Islam (the Middle East, the southern rim of the Mediterranean, and Spain). During the period from 500-800 there was little cultural or scientific advancement in Western Europe, and it has come to be known as the Dark Ages. Slowly, social institutions matured as conflict dissipated. The High Middle Ages from 1050-1350 brought an era of creativity that concluded with the Renaissance. The culture of Western Europe was a merging of classical (Greco-Roman), Christian, and Germanic elements. The Germanic people – whose invasions were a factor in bringing down the Roman Empire – were less educated and cultured than the Romans. They brought a switch from urban to rural culture, and education, literature, and the arts declined. The Germanic tribes spoke closely related languages and shared similar physical features including tall stature, fair skin, blond hair, and blue eyes. Before historic times they lived in areas of Scandinavia and northern Germany. Their society was based on hunting, herding, farming, and pillaging. The Germanic religion was polytheistic. They had a reverence for nature spirits living in trees, rivers, mountains, and animals. Deities included Tiu (Tuesday), Woden (Wednesday), Thor (Thursday), Frig (Friday), and Eastre (the goddess of Spring). Their pagan religion had a weak hold on them, and the Germanic people easily converted to Christianity. Of the numerous Germanic tribes, most assimilated into the cultures they conquered. They respected the ways of civilization and sought to imitate them. Two tribes succeeded in building permanent states: the Anglo-Saxons and the Franks. The Anglo-Saxons came from the area that is now Denmark. They crossed the North Sea and invaded Britain during the 5th century after the Romans had withdrawn. They established several kingdoms, but Scotland and Wales retained their independence. In the 10th century, the separate Anglo-Saxon states combined into a single kingdom – Angleland. Teutonic (German) language and customs had taken over. The Franks originally came from the areas of modern-day Germany and Belgium. They came to power under the brilliant, but ruthless, leadership of Clovis. Clovis eventually conquered the lands from the Pyrenees Mountains to the Rhine River in Central Europe. Upon the urging of his wife, Clovis became a Christian. This brought the support of the church in Rome. Instead of overthrowing the existing Roman political institutions, Clovis put them under the control of the Franks. When Clovis died in 511, his lands were divided among his four sons, according to Germanic custom. Clovis’s family ruled until 751, but their power was in decline by the mid-600s. The Mayor of the Palace (the chief court official) became the main ruler of the Frankish kingdom. By 700, the king was merely a figurehead. The nobility were in control, and the main elements of the feudal state were established. For over a century, the Carolingian family was responsible for the defense and administration of the Frankish kingdom. Although only figureheads, the descendants of Clovis would not relinquish the crown. Charles Martel was the Frankish Mayor of the Palace when the Battle of Tours broke out in 732. Martel rallied Christians against the invading Muslims. His victory was a turning point in history that earned him the nickname “the Hammer” and set the stage for his family’s ascension to power. Martel’s son Pepin approached local bishops who refused to help him depose the reigning monarch, so he went to the pope who approved the deposition. In 751, Pepin was crowned king of the Franks, but he owed the pope a favor. Pope Stephen II visited Pepin in 754, anointed him as king, and received promises of military assistance. In 756, Pepin and his military crossed the Alps and defeated the Lombards who were threatening the power and territories of the papacy. Pepin went on to transfer a strip of territory across central Italy to the governing authority of the pope, which became know as the Donation of Pepin. The States of the Church became a sovereign political entity and remained one for a thousand years, until the unification of Italy in 1870. The action of Pope Stephan II anointing Pepin as king symbolized the strong ties between the king and the church, and later popes used this incident to justify their claims over political rulers. The most famous of all Carolingian rulers is Charlemagne – Charles the Great. The term Charlemagne was not used until a hundred years after the death of the son of Pepin, whose given name was actually Karl. Nevertheless, during his forty-six-year reign, Charlemagne restored a measure of unity to Western Christendom and expanded its frontiers. Charlemagne personified the merging of Greco-Roman, Christian, and Germanic elements with “the Roman idea of universality and order, the Christian religion, and Frankish military power” (Greer 182). Charlemagne brought on what was later known as the Carolingian Renaissance. His court at Aachen was the most important stone building erected north of the Alps after the fall of Rome; the chapel was modeled after the Byzantine church of St. Vitale. Artisans and artists were imported from Italy, thus stimulating the development of the arts in Northern Europe. Concerned about the low level of education and scholarship in his realm, Charlemagne set up a palace school in 780, which became a center of intellectual activity. He recruited a monk named Alcuin – the leading scholar of his day – from the cathedral school at York, (the finest academic institute in England), to head a faculty of distinguished scholars from all over Europe. Alcuin trained a staff of expert scribes to reproduce ancient manuscripts. He issued a decree instructing bishops and abbots to improve the training of the clergy. In monastery schools, students learned Latin, the language of the church, and monks made copies of the Bible and the few surviving Greek and Roman texts. Monks developed the art of illumination wherein the first letter of a paragraph and the margins of a page were decorated. Lower case letters, called Carolingian miniscule, were also invented at this time. Charlemagne was almost constantly at war, fighting for the higher goals of Christianity and universal order. Like his father, he defeated the Lombards in 774. Afterwards, he called himself king of the Lombards as well as king of the Franks. He fought against the Saxons for 30 years. They were the only heathen Germans left, and Charlemagne was determined to turn them into loyal Christian subjects. They were finally defeated after their homeland to the north and east of the Franks was laid to waste, many people were massacred, and the rest were relocated to other parts of the empire. Charlemagne created military zones to separate the Christians from the remaining heathen. Danemark separated the Danes for over a century, until the Danish king converted to Christianity. Nordmark on the eastern front separated the Slavs; it later became the Duchy of Brandenburg, which later became the state of Prussia. Ostmark or East Mark held back the Mongolian Avars; this eventually became the Duchy of Austria. Finally, Spanish Mark held back the Muslims south of the Pyrenees and later allowed Christianity to spread to the kingdoms of Aragon and Castille. Regarding domestic policy, Charlemagne allowed the various territories to govern themselves according to their own laws. However, royal inspectors called missi dominici, that consisted of a nobleman and a clergyman, visited each territory once a year to check up on the performance of local nobility. Charlemagne’s territory was organized into regions in a system inherited from earlier kings and Roman rulers. Counts represented the crown in an area called a county. They presided over a court that met monthly, collected fines, and in times of war assembled knights for military action. Dukes represented several counties. Both dukes and counts were chosen from the local landed nobility. What was termed as the “Restoration of the Roman Empire” occurred on Christmas Day 800 when Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne as Charles Augustus, Emperor of the Romans, in St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. The pope did this to obtain a strong protector from what could be a dangerous adversary and so he could further separate himself from the Byzantine government. Although Charlemagne was happy to receive the honor, technically there was already an “Emperor of the Romans” in Constantinople – a woman named Irene. However, according to Roman tradition, women were considered ineligible to rule, and thus the pope had elevated Charlemagne to what he considered a “vacant” throne. By his action as donor of this honor, the pope had secured a position of superiority over the emperor, who would be under obligation to the papacy. Later popes would claim that they had the right to withdraw what had been given to unseat emperors. Despite his impressive accomplishments, there were some significant differences between the Roman Empire and Charlemagne’s empire. Charlemagne’s territories had no single citizenship, no unified law, and no professional civil service. Few cities had survived, and roads were in a state of disrepair. Although Christianity was the main unifying force, the agencies of the church did not compare to the firm political institutions of Rome. And finally, Charlemagne’s empire was held together on the basis of his personality, and after his death in 814, it basically fell apart. For 30 years, his heirs battled for power, until his grandsons drew up the Treaty of Verdun in 843, which divided the empire into three regions. Feudalism and the Manor System As Roman civilization declined, Europe became an isolated land of disunity, conflict, and poverty. After the death of Charlemagne, internal divisions and invasions once again disrupted European life. Feudalism evolved from the loosely organized system of government in which local lords governed their own lands but owed military service and other support to a greater lord. Diocletian began the process when he tied the peasants to the land, and it progressed when Charlemagne consolidated the structural organization of this political system. The king was at the top of the feudal pyramid with barons, dukes, and counts progressively below him. Through interdependence and mutual responsibilities, feudalism provided people with protection and other benefits. While feudalism brought political structure to the early Middle Ages, the manor system was responsible for providing economic and social structure. Fiefs were miniature governments based on self-interest and mutual defense, where there was an exchange of property for personal service. A fief was the land granted to a noble by his lord. It included one or more villages and all surrounding lands. A great fief was subdivided into hundreds of smaller estates called manors that ranged in size from 300 to 3000 acres. However most were about 1000 acres and supported 200 to 300 people. Vassals protected the inhabitants of his fief, collected revenue (taxes), and dispensed justice. Serfs were tied to the land. They were not allowed to leave the manor, other than to go to fairs, nearby towns, or on a yearly pilgrimage to a Christian shrine. Even when permitted to travel, few chose to because the roads were poor, there were few hostels, and there was widespread banditry. The lord of the manor traditionally took half the produce of the estate to feed his family and personal aides, to give to his overlord, and to put in storage to reserve for years of crop failure so that the peasants could be fed. Peasants were either serfs or freemen. As noted, serfs were bound to the land, and members of their family could not leave the land or even marry without the lord’s permission. However, they could not be evicted from the land. Serfs were required to do any labor the lord demanded, such as clearing forests, building roads, etc. They also had to work a plot of land for the church, God’s acre. Freemen had ancestors who had avoided the commitment of perpetual servitude. They were merely tenets on the land, who paid rent to the lord in the form of a share of the crops. They could be evicted at any time and had no guarantee of protection from the lord. Village life was not pleasant. Homes were tiny, usually only one room. There was a lack of privacy, and usually the whole family along with their animals slept together. Illiterate and uneducated, peasants lived a very simple life. Husbands and fathers had full control, but the whole family toiled together in the fields. Agriculture was the primary economic activity on the medieval manor. There were many improvements during this period thanks to a variety of innovations. The threefield system of crop rotation brought greater yields. In this system, one field was planted with grain, another was planted with beans, and the third was left fallow – not planted with crops – but enriched with night-soil. Each year the fields were rotated, thereby renewing the soil. Other improvements included iron plows replacing wooden plows and horses replacing slower oxen after the horse collar was adopted as a new kind of harness and iron horseshoes were utilized. Finally, windmills were introduced to grind grain into flour in areas where a watermill could not be used. While the life of a peasant was monotonously simple, the life of a noble was considerably more complicated. In an act of homage, each vassal had to swear a pledge of loyalty to his lord. Vassals owed their lord military service by furnishing himself and a body of armed men. In the beginning, there was unlimited service, but later service was limited to 40 days a year. Vassals also had to serve on the lord’s court which met once a month to hear disputes of vassals over land, interpretations of feudal rights, and criminal charges. The lord would preside at court, and the vassals acted as judges. Armed conflict could result if the losing party refused to accept the decision. “When evidence was lacking, the court might require individuals to walk barefoot over hot coals, or thrust their arms into boiling water, or risk personal injury in some other way. It was believed that God would save them from harm if they were innocent and telling the truth. But bodily damage from such a test was seen as proof of guilt, and the court imposed the customary penalty for the alleged crime” (Greer 186). This custom was called trial by ordeal and went on until the 13th century. Vassals were also required to provide their lord with certain payments called relief. This usually consisted of giving the first year’s income to the lord after receiving a fief. Hospitality to the lord, his family, and attendants involved providing food, lodging, and entertainment for a given amount of days each year. Payments were also made to the lord on special days, such as the knighting of his eldest son and the marriage of his eldest daughter. And if the Lord was captured in battle, his vassals were required to pay his ransom. Vassals could hold fiefs from more than one lord; however, the liege lord received primary loyalty in cases of conflict between overlords. It was common to be both a lord and a vassal. Everyone in medieval society had a clearly defined role. The nobility was a military aristocracy that held political and economic control. Land equaled power. Knights were mounted warriors. Chivalry was the code of conduct which required knights to be brave, loyal, and true to their word. Women’s rights were generally restricted, but noblewomen played significant roles. The property of a monastery was a fief that had the usual military, financial, and political responsibilities as a vassal. Medieval society was divided into three estates. The clergy (guardians of peoples’ souls) were the first estate, the nobility (protectors of life and property) were the second estate, and the commoners (peasant farmers - 90% of the population) were the third estate. The Roman Catholic Church The Roman Catholic Church was the primary institution of medieval society. With both spiritual and secular power, the church dominated life. Since it was believed to be the only way to salvation (eternal life in heaven) and the prospect of heavenly rewards held strong appeal, the church possessed immense influence. Given that people did not want to burn in hell for their sins, they obeyed canon (church) laws and participated in the sacraments (sacred rituals of the church). Failure to obey could result in excommunication, wherein you could not receive the sacraments, which were considered to be the only way to avoid the tortures of hell. In addition, good Christians were required to shun you. A noble who violated church laws could face an interdict, which meant that his entire fief was excluded from receiving the sacraments. Popular pressure would soon force the noble into obedience. The saints were the heroes of the Middle Ages, (as the epic warriors had been the heroes of classical Greece). This included the 12 apostles, the early martyrs, and the Virgin Mary. The saints were called upon frequently. Oaths and treaties were sworn on saintly remains. These relics were carried in religious parades. The skulls, bones, and hairs of saints were very popular. Stranger relics included sweat, tears, the umbilical cord of Jesus, St. Joseph’s breath, and the Virgin’s milk. Fragments of the “true cross” were everywhere. And there were several heads which were claimed to be of John the Baptist. The genuineness of these relics was not questioned by the faithful. However, by the end of the Middle Ages, even some devout Christians began to express doubts of their authenticity. The clergy was divided into two groups. The secular clergy were the parish priests, and the regular clergy lived in monasteries. It was the monks in the monasteries that kept literacy and learning alive. They provided elementary education for youths planning to enter the clergy, and they preserved and copied manuscripts. These manuscripts became known as illuminated manuscripts because the monks illuminated or illustrated each page by decorating the letters and framing the text with intricate designs, biblical scenes, or portrayals of daily life. Copying the Bible was considered to be a form of worship, and thus the beauty of the illuminations had to match the importance of the content. At first, there was some hesitation to render images of Christ and other holy persons, but in the 6th century, Pope Gregory the Great proclaimed that “painting can do for the illiterate what writing does for those who can read” (Prentice Hall: TE 193). Copyists labored in workshops called scriptoria. They became specialists at their work. Antiquarii created the calligraphy. Rubricaores illuminated the initial letters. And miniatores illustrated the margins. The work of writing and illuminating manuscripts was a way of “fighting the Devil by pen and ink” (Prentice Hall: TE 193). Church Corruption was a major issue in the Middle Ages. Monks swore vows of poverty, but monasteries got rich and many abbots lived elegant lives. In addition, obedience to monastic rules weakened, such as vows of chastity, physical labor, and the arts of reading and writing. Powerful nobles had control over the appointment of Bishops and Archbishops and began selling these offices, this practice was known as simony. Some parish priests were illiterate, and some had wives and children. Distressed by widespread corruption, the Monastery of Cluny in France began a reform movement in the early 900s that helped restore discipline among the clergy. Pope Gregory VII extended the Cluniac reforms throughout the entire church in 1073.