Research Study on International Recycling Experience

Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs

Research Study on

International Recycling Experience

Annex A

A5 NETHERLANDS - ARNHEM

A5.1 OVERVIEW

A summary description of Arnhem and key recycling data are presented in Table A5.1.

Table A5.1 Overview of Arnhem

City

Background

Population

Density

Details

137 295

1350/km2

Type of Area Urban

Type of

Housing

Approximately 33% apartments and 66% semidetached houses.

Definition of

MSW

Target

Hazardous and non-hazardous household waste and similar commercial and industrial waste, including construction and demolition waste and parks and gardens.

The national goal for the household sector is 60% reuse and recycling by 2000 which comprises:

non-returnable glass packaging: 90%;

paper and board: 85%; textiles: 50%.

Achievement 37% of household waste (1998).

Principal recycling drivers

landfill ban on household waste; regulatory requirement for separate collection of different waste components of household waste; producer responsibility;

level of environmental awareness.

Arnhem is reasonably representative of recycling rates in the

Netherlands. The type of housing and income distribution is also representative.

A5.2 RECYCLING TRENDS

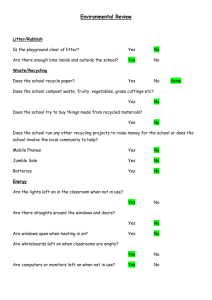

Figure A5.1 shows the amounts of materials re-used and recovered in the household sector in Arnhem in 1998. These figures reflect the majority of domestic recycled material, collected from the kerbside and from bottle banks.

Figure A5.1 Quantities of materials reused and recycled in the household sector, 1998

No data on trends in the recycling of materials were available for Arnhem. Disaggregation of data on re-use and recycling levels was also not available from the municipality.

A5.3 MSW MANAGEMENT STRUCTURE

The municipality of Arnhem has devolved collection duties to a privatised company called ARA. This company has a 75 per cent shareholding by the municipality and a 25 per cent shareholding by private companies. MSW management was privatised with the objective of lowering costs and up-

grading facilities. Commercial targets are set for the company and its contract comes up for renewal every 10 years.

A5.4 COLLECTION MECHANISMS AND

ACCESSIBILITY OF RECYCLING FACILITIES

Table A5.2 Collection Mechanisms

Material Collection method

Organic

Houses: kerbside;

Apartments: containers.

Density/coverage

100%

Glass

Paper

Collection is every two weeks.

Bottle banks. One bottle bank for

1373 people.

Voluntary collection by 'paper clubs' organised by schools and sports clubs. The clubs get paid 3.5 ct/kg.

100%

Plastics None.

Bulky waste ARA come to collect within two weeks.

-

General Retourette , or collection point within the supermarket.

One n/a

Household hazardous

Waste pickups by bus.The waste calendar advises households of the schedule. n/a

For apartment blocks, separate containers are provided for organic and other waste. The distribution density of containers is such as that people do not have to walk more than 100 metres to a set of containers. The vast majority of residents of Arnhem are covered by this two-container system. Around 150 households, concentrated primarily in deprived city areas, are not covered.

It is not considered cost effective to recycle plastics.

The supermarket collection point (retourette) is a new initiative. All kinds of waste can be delivered to the retourette, including paper, medicine, textiles and glass, which is collected by ARA. There is currently one retourette in

Arnhem. The supermarket pays for the retourette and it is often used as a marketing instrument. This pilot shows that the uptake of separated waste was 600 per cent higher than

the other collection points in the area. The supermarket increased its turnover by 10 per cent (500 customers per week). In 1999, 35 tonnes of waste, excluding glass, was collected.

Arnhem has two recycling centres. Residents can take larger waste items to these centres. Costs are applied on the following basis:

Table A5.3 Charges Levied at Recycling Sites

Type of waste Charge

Garden waste Anything over 1 m3 is charged at fl 40 (£ 11) per m3.

Rubble/soil Any more than 30 litres is charged at fl 40 per litre

(clean) and fl. 80 (contaminated).

Any more than 1.5 m3 is charged at fl 40 per m3. Large household waste

Asbestos

Car tyres

If used as a floor cover, quantities over 1.5 m3 is charged at fl 40 per m3. If used as a building material quantities over 2 m3 is charged at fl 40 per tonne.

Each is charged at fl 7.5 (£ 2).

Material

Organic

Paper

ARA is working towards a better system of control over the users of the recycling centres. Currently, unauthorised people, such as those from other municipalities, and the commercial sector, use these facilities.

A5.5 COSTS AND REVENUES

ARA receives income from the services it provides to the municipality for collection and recycling, and from sales of recyclate. ARA is self sufficient in funds.

Table A5.4 Costs of Recycling in Arnhem, 1998

Costs of re-use/recycling (£/tonne)

Collection Treatment Total

82 (788 825) 37 (352 780)

118.44 (1.14 m)

31.64 (173

442)

12.60 (68

419)

44.20 (241

862)

Glass

Household hazardous waste

27.44 (69 827) 7.84 (19 811) 19.60 (50 017)

4 (96 010) 0.39 (9466) 4.39 (105 476)

Note: Using an exchange rate of fl 1 = £ 0.280 (FT 14/02/00)

A5.6 CRITICAL SUCCESS FACTORS

Currently the most significant factor in encouraging high recycling rates nationally is the landfill ban for organic waste, see Section A5.7.

Producer responsibility for various waste streams was introduced in 1995.

In the first half of the decade, information campaigns, the requirement to collect organic waste and other waste components from household waste separately and extensive monitoring of waste collection and waste treatment data were the principal drivers.

A5.7 LEGAL/REGULATORY REQUIREMENTS

The Waste Management Council (AOO) was established in

1990 to co-ordinate waste policy implementation at national, provincial and local level. The central task of the AOO is to reach agreement on the processing and disposal capacity necessary for waste disposal. The Ten Year Waste

Management Programme (1995-2005), developed by AOO, shows that the processing capacity available in the

Netherlands will be sufficient for several years as long as waste prevention and recycling proceed according to the national target of 60 per cent recycling of household waste by

2000. The model held up by this programme is as follows:

glass collection by means of bottle banks with a distribution density of one container for every 650 residents;

kerbside collection of paper and cardboard at least once a month.

The Waste Chapter of the Environmental Management Act

(1994) makes local authorities responsible for collecting organic and other household waste from the kerbside once a week. Local authorities can deviate from this regime to

increase the efficiency of recycling. The Act also rules that, by 1997, provinces need to have organised separate collection of dry components of the household waste stream such as glass, paper, textile and hazardous waste. An increasing number of municipalities have replaced kerbside collection by recycling containers. This practise is allowed, providing that the maximum distance from a container to a premises is no more than 75 metres.

Under the Waste Decree of 1995, household waste can no longer be sent to landfill. Exemption is granted where there are shortages of incineration capacity, as is the case in

Arnhem.

Producer responsibility has been introduced for several waste streams, making importers/producers responsible for the treatment of their products once they reach the end of their life. Around 80 per cent of household waste is covered by some form of producer responsibility system.

The landfill ban on household waste is currently the strongest driver of recycling activity in the Netherlands. However, recycling activity had started previous to this, driven by the following factors:

in 1993 an Action Programme in the Separation of

Dry components required the Waste Management

Council to develop a strategy of separate collection of

the dry of components of the household waste

in 1993, the Waste Monitoring Platform was set up to co-ordinate various waste monitoring activities in the

Netherlands;

in 1993, guidelines of the construction and operation of landfills became law, thus raising the cost of landfill;

the first 'Ten Year Waste Management Plan' (1992) set out a tightening of incineration capacity;

public information campaigns have always been an important policy instrument in the Netherlands.

Landfill costs rose dramatically in a short time and this can, at least in part, be attributed to the raising of standards for landfill construction and operation in 1993.

A5.8 FISCAL INCENTIVES

A5.8.1 Waste Disposal Costs

The municipality of Arnhem incinerates around 61 per cent of household waste arisings. The municipality of Arnhem does not own incineration facilities. Each tonne of waste incinerated is charged at fl 229 (£ 64.12) per tonne.

The average cost of landfill for non-hazardous waste was fl

145 in 1996 (£40.60). The landfill tax stood at fl 30 (£8.40)

for non-incinerable waste and fl 70 (£20)

waste in 1998.

A5.8.2 Charging Systems for Waste Management

Waste charges are covered by a monthly flat-rate tax. The average per capita waste levy has doubled since 1991 to 1997 and stood at fl 377 (£105 ) in 1997.

A5.9 PUBLIC AWARENESS

The waste calendar is the most important piece of communication. This makes it clear to households when they should put out waste or to where they can deliver it. The population of Netherlands generally possesses a high level of environmental awareness.

A5.10 MARKETS FOR END PRODUCTS

Generally, there are stable markets for recovered paper and glass, but the price of recycled paper is volatile. In situations of low prices, local authorities may give collected paper to the processing industry for free.

Compost has been heavily promoted and the market has grown considerably. The Decree governing the quality and the use of organic fertilisers sets standards for the use of compost. In addition, industry has developed a quality certificate of their own for compost. The first certificate was issued in 1997. In 1998, 1.5 million tonnes of organic household waste was collected nationally and more than 500

000 tonnes of compost was produced by the 24 Dutch composting facilities. Much of the compost is priced modestly, suggesting that the production of compost is supported by revenues from other areas of the waste management system.

Table A5.5 indicates how compost is used:

Table A5.5 Compost Markets (in kilotonnes)

Sector farms

Agriculture, horticulture, arboriculture, flower bulb

Green areas

1997 1998

281

(52%)

230

(49%)

18 (3%) 30 (6%)

Private sector

178

(33%)

122

(26%)

Municipality

Export, landfill construction

12 (2%) 19 (4%)

51 (9%) 69 (15%)

Note: the percentage figures in brackets indicates the proportion of compost used in that category from the total amount produced.

[1] The targets set for 2000 under the Programme for the Separate

Collection of Waste are paper and cardboard: 85 per cent (72 kg per capita per annum); glass packaging: (25 kg per capita per annum) and textiles: 50 per cent (5 kg per capita per annum).

[2] The costs for 1996, 1997 and 1998 have been converted to Sterling using an exchange rate for the 14/02/00.

[ Previous ] [ Contents ] [ Next ]

Published 26 April 2001

Waste Index

Environmental Protection Index

Defra Home Page

![School [recycling, compost, or waste reduction] case study](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/005898792_1-08f8f34cac7a57869e865e0c3646f10a-300x300.png)