600syll - Bryn Mawr College

advertisement

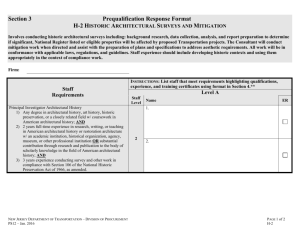

HSPV 600: Documentation and Archival Research Mondays, 9-12, Meyerson Hall B6 J. Cohen [jcohen@brynmawr.edu] Goals and Rationale: The goal of this class is to help students build on their understanding of materials that record and contextualize the history of places. Historic preservation is based ultimately on our appreciation for the buildings and landscapes of the past. A key part of our attraction to them lies in the authenticity of their testimony about the lives and ambitions they physically represent. It is easy to be glib about that, and one commonly encounters facile story-telling attached to historic places, but the power of the built artifact lies in its membership in a realm that transcends those narratives we attach to them. In their material form they embody some degree of historical reality, a connection to a whole range of contexts from their world that trumps our reinventions and stories. That reality has a capacity to draw many of us to these timetravelers. They enlist our deference and our service to help them persist in their material form and in their power to connect with others. Our role, as preservationists, is to help such an artifact speak its reality, to convey to modern audiences the meanings of its genesis and life, and to frame it amid the forces and the contexts that shaped it. We must be humble about our ability to know these things from our present-day perch, often distant in fundamental ways from the circumstances and intentions that produced a place. We are left only imperfect means to cobble together their stories and meanings, but it is incumbent on us to try to understand these buildings or settings as best we can, whether that informs a short brochure, broad policy arguments about what merits society's protections, or specific decisions on which aspects of a historic building deserve conservation. Our tasks are bedded in an effort to understand the complex objects and places under our consideration, to understand the sources and limits of our historic knowledge, and -whether our immediate task is one of conserving materials, administering historic certification processes, devising programs for a house museum, or any of a dozen related roles -- of keeping in mind the bigger picture, of how the future benefits from our efforts in these cases to help the past persist. Even where we are only asked to fill in the boxes on a form, we should keep an eye on the farther horizon, whether that helps us perform our immediate task more effectively or leads us to question and shape processes that are the instruments of our intentions. The historical reality we seek to understand is usually elusive and multivalent. It may lie at the intersection of many narratives: of the trajectory of its owners' ambitions, the evolution of its locale, the changing building technology of its time, the class structure it inhabited, the cultural referents of its users, the reigning architectural dialogue of its day, or the economic marketplaces it inhabited. The evidence for most of these narratives is incomplete, potentially skewed, or embodied in analogous objects rather than anything specific to this one. It may be coded in patterns of land use, contractual language, financial transactions, and tides of stylistic change. It is often dispersed among many places, sometimes with little trail by which to track it. The results of our research, of our effort to understand, may be at best a patchwork, riddled with conditional judgments, argument by comparanda, and qualified assertions rather than the clear and often-inflated superlatives -- "the finest example . . .," "the earliest . . .," "among the most significant . . ." -- that have become all too common, if not required by our procedures. But what is lost in simplicity may be gained in credible textures of nuance and evidence. The best historical work will integrate a sense of how we know, and will share with the reader the sense of process in this rediscovery of a world now passed. "How we know" can be an engaging part of the story, and the potential to engage, rather than pieties or superlatives, is the strongest argument for the physical preservation of historical places. It is the currency that returns the present's investment in the past, that justifies our society's efforts in maintaining the historical object into the future. And that is all predicated on our knowing the place as best we can in all its richness and complexity, and conveying that knowledge in ways that will honestly and engagingly connect with sustaining audiences of interest. The Course: If that was an overlong way to assert that history and a developed understanding of its sources are critical to all of those involved in historic preservation, it remains to us, in defining our activities in this class, to undertake exercises that will serve these goals. As in past iterations of the course, under Dr. Moss, a centerpiece of the class will be firsthand exposure to the actual materials of building histories. We will visit a half-dozen key archival repositories, and students will work directly with historical evidence, both textual and graphic, exercising their facility through projects. We will explore various forms of documentation, discussing each in terms of its nature, especially the motives for its creation and some ways it might find effective use. Philadelphia is more our laboratory than a primary focus in terms of content, as the city is extremely rich in such institutions that hold over three centuries worth of such materials, and students will find here both an exposure to primary documents of most of the species they might find elsewhere, as well as a sense of the culture of such institutions and the kinds of research strategies that can be most effective. Architectural research almost always involves a measure of triangulation between documents and survivals at different locations, along with connections to larger contextualizing narratives. As will be the case for any location, knowledge of the local architectural history will serve in important ways. A strong knowledge of Philadelphia's evolution, her key landmarks, building patterns, and architects will help greatly, providing a more meaningful setting for our sharply focused class projects and erecting a richly inhabited chronological framework to call upon for comparative purposes in other historical inquiries. The projects this year will be a bit different than in the past. Rather than focusing on the oldest kinds of manuscript documentation, on deeds and wills, we will turn more toward historical documentation of the later 19th and 20th centuries. And rather than focusing individually on a single property "from soup to nuts," we will work mainly on group projects that are organized topically in different ways, around a potential research resource or an architect's work, for example. A collateral goal that we will take seriously as part of our exercise will be to build resources for others to use, taking pains to make them reliable and useful, combining issues of research with those of presentation. In most cases, it will be expected that the final result will be able to take an electronic form and be placed on the Web for the benefit of future researchers. We will do two sequential sets of group projects. The first set, earlier in the semester, will address more discrete kinds of documentation that will tend toward a more elite aspect of the built landscape, while the second will look toward the more anonymous, the typical, the work of builders and developers rather than professional architects, and toward the dominant textures of urban life more than the extraordinary design. (If there will be somewhat less emphasis on deeds and wills in this year's course, we will go over the processes and purposes involved in such research, but rather than carrying these out, we will reserve the measure of tedium in that for some other purposes. As for the National Register form exercise that was once part of the class, we will again look at the result and discuss the process. But in either case, if students would like to substitute these tasks for participation in the group project, or would prefer top work alone rather than in a small group, that may be arranged with the instructor.) The first project will deal more with the kind of buildings that architects may have designed individually, or documents about that sort, more about the extraordinary than the typical. Some initial first project ideas: • a. Webbing, mapping a photograph collection. • b. Nailing down an architect's work. • c. Tracing the evolution of downtown blocks. • d. Surveying a document type. • e. Annotating and illustrating period writings. • f. Collecting images and data from a rare architectural journal. These are some suggested topical frames, and will be fleshed out with particulars. Ideas for analogous ones should be brought to the instructor, keeping in mind that they should be achievable with about three weeks of work. The second set of projects will be more aimed at older sets of buildings, typically not involving professional architects, at resources for studying urban vernaculars, buildings that define common types, at settings that are the work of speculative developers, and at patterns in urban development. This may involve projects that treat some antebellum graphics collections, or look for patterns from tax records, club registers, business directories, and fire insurance surveys. Reading: on local resources J. Cohen, "Evidence of Place" Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 124, nos. 1/2 (Jan./Apr. 2000): 145-201. Jefferson Moak, Architectural Research in Philadelphia, rev. ed. (Philadelphia, 2002). on Philadelphia's architectural history: George B. Tatum, Penn's Great Town (Philadelphia, 1961). J. F. O'Gorman et al., Drawing Toward Building (Philadelphia, 1986). web resources: Philadelphia Architects and Buildings project [http://www.philadelphiabuildings.org/pab/] Places In Time: Historical Documentation of Place in Greater Philadelphia [http://www.brynmawr.edu/iconog/] other RM Readings: National Register Bulletin 39: "Researching a Historic Property" (1991) National Register Bulletin 16A: "How to Complete a National Register Registration Form." J. B. Post, "Historical Map Research," Library Trends (Winter 1981): 43951. Jo Brisbane, "Fire Insurance Maps," Blueprints (Summer 1987): 10. 600syll.doc; last rev. 12 Sept 04 jc