Open Sesame! Network Attack Literally Unlocks

advertisement

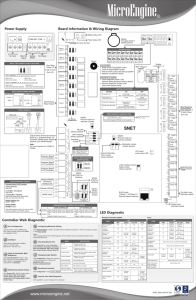

Open Sesame! Network Attack Literally Unlocks Doors By Kim Zetter August 1, 2009 | 2:37 am | Categories: Cybersecurity, DefCon LAS VEGAS — Security researchers have spent a lot of time the last couple of years cracking building access systems from the level of the user device — RFID and smartcards, for example. But a researcher in Texas found that he could crack one electronic access system at the network control level and simply open a door with a spoofed command sent over the network, eliminating the need for an access card. He could do it while bypassing the audit log, so the system wouldn’t see that someone opened the door. The hack is possible because the system uses predictable TCP sequence numbering. Ricky Lawshae, a network technician for Texas State University, presented his findings on Friday at the DefCon hacker conference. Lawshae focused on only one system used at his university — CBORD’s Squadron access control system used with HID Global’s V1000 door controller. CBORD’s system is used in a number of universities and health care facilities across the country, according to its web site. At each door is the controller, with a card reader and electronic lock. The controller connects over TCP/IP to a central server that in turn connects to a client program that is used to change access privileges for cardholders, monitor alarms and remotely lock and unlock doors. The problem occurs between the door controller and the server, which communicate with a persistent TCP session with “very, very predictable sequence numbering,” Lawshae says. Essentially, it increments by 40 for each new command. This means an attacker on the network can, while conducting a man-in-the-middle attack, intercept a “door unlock” command and easily guess the next sequence number. Then, any time he wants to open a targeted door, he can sniff a packet to determine the current sequence number, and send an “unlock” command into the session with the next sequence number and the IP address of the administrator, fooling the system into thinking it’s a legitimate command. The command could remotely unlock one door or all the doors on an entire facility. The command won’t appear in the log because it’s sent directly from the attacker to the door controller, bypassing the administrative server. Lawshae says the attack could be thwarted if the vendor used a random number generator that would make guessing the sequence difficult or encrypted the communication between the server and the door. Lawshae told CBORD about the vulnerability, and the company is working on an update. He says university officials “were not as terrified” as he thought they would be by the information but took some precautions anyway, such as placing the controllers on a virtual local area network to make it more difficult for an attacker to conduct a man-in-the-middle attack.