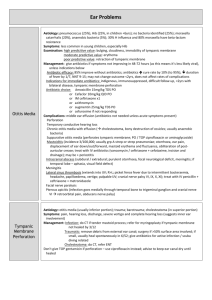

OTITIS MEDIA AND OTITIS EXTERNA IN ADULTS

advertisement

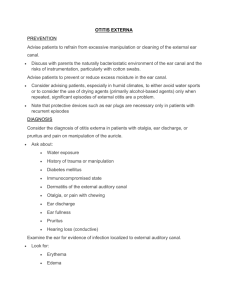

OTITIS MEDIA AND OTITIS EXTERNA IN ADULTS Jeff Stein, M.D. WEEK 11: 03/14 – 03/18/05 Learning Objectives: 1. Describe diagnostic features, and a short differential diagnosis of, otitis media and otitis externa in adults 2. Prescribe appropriate therapy for uncomplicated cases of otitis media or externa 3. Recognize more serious variants or complications of these conditions Author’s Note: Acute otitis media (AOM), the most common type of “ear infection” in children, is much less frequent in adults for a variety of reasons including evolution of eustachian tube anatomy, decreased frequency of viral URI’s, etc. There is correspondingly much less literature on this problem in adults; the clinical approaches described in most references are often extrapolated from those in children. Nonetheless, you are likely to encounter both otitis media and otitis externa in adult patients. CASE ONE: A 25-year-old woman presents with unilateral ear pain of several hours duration. The pain has now developed after several days of a viral URI, characterized by nasal congestion and mild cough. It’s worse with swallowing. The patient has no associated dizziness or fever, but the ear “feels like it’s blocked.” PMHx reveals no major medical problems. There is no history of recent ear trauma or infections, though she had many of the latter as a child. Questions: 1. Assuming the remainder of the exam is normal in each case, describe your clinical impression and management plan if the ear exam shows: a. An intact, patent ear canal and the tympanic membrane have a dull appearance, with clear fluid and a couple of small bubbles visible through the TM in the middle ear. This patient has a middle ear effusion; the effusion and associated symptoms may be the result of virus-associated eustachian tube inflammation and dysfunction +/- a viral infection of the middle ear. Early bacterial otitis media is a possibility, but a trial of an analgesic alone (such as an NSAID) would be reasonable, with re-evaluation as needed if symptoms persist. b. An intact, patent ear canal with a red, bulging tympanic membrane and opaque fluid behind it This is a classic constellation of findings for acute suppurative otitis media caused by bacterial superinfection of a stagnant middle ear effusion (see above). The usual therapeutic approach involves prescription of oral antibiotics. Theoretically, these would be chosen to cover the most likely pathogens. [Ask what these are] Answer= Strep. pneumoniae, non-typable Hemophilus influenzae, moraxhella catarrhalis, and less often, Strep. pyogenes or Staph. aureus]. In practice, amoxicillin is often used initially, even though some H. influenza and most Moraxella catarrhalis are betalactamase positive and resistant in-vitro. This approach often works anyway due to the high spontaneous cure rate, even without treatment. [Refer housestaff to the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews- those on otitis media therapy fail to describe much benefit, although most of the data is from children.] First-line alternatives would also include TMP/SMX, second-generation cephalosporins, later-generation macrolides, and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid. Non-antibiotic therapies such as decongestants, directed at the eustachian tube dysfunction, have also been tried, but have not been shown to be effective in treating the infection itself. c. Tympanic membrane as in (b) and the ear canal have some mild swelling and erythema along the posterior wall. There is also some mild postauricular erythema, swelling, and tenderness, and questionable slight protrusion of the pinna compared with the contralateral ear. The external and periauricular features here, including displacement of the auricle, indicate acute infectious mastoiditis complicating the picture of acute otitis media. The prominent tympanic membrane and auricular/periauricular findings relative to the limited canal involvement also serve to distinguish this from otitis externa. While the mastoid air cells, contiguous with the middle ear, often develop subclinical inflammation/infection in AOM, clinically evident mastoiditis, as in this case, is a serious problem that may require hospitalization, parenteral antibiotics, and otolaryngology should be consulted promptly. d. An intact, patent ear canal with dull tympanic membrane (TM) containing patches/plaques of embedded white material The white material is a “red herring” (no pun intended!)- it represents tympanosclerosis, a common scar-like sequella of recurrent otitis media. It would not be expected to cause her symptoms. This patient may have eustachian tube dysfunction as in part (a). CASE TWO: A 55-year-old man presents with unilateral waxing/waning ear pain for the past week. He had a URI a few weeks ago, but most of his symptoms resolved except for some frontotemporal headaches. When seen by you three months ago for a routine physical exam, he had an asymptomatic middle ear effusion on that same side. 2. Describe your clinical impression and plan if ear exam today showed: a. Normal landmarks and anatomy The absence of middle ear findings should raise index of suspicion for referred pain from other head/neck problems (e.g. TMJ dysfunction, sinusitis, dental problems), and further evaluation focused on these possibilities. b. Findings similar to Case 1(a) A persistent middle ear effusion, while possibly residual from a recent URI, should raise the possibility of other causes. Most concerning, though not common, is the possibility of an occult head/neck tumor in an adult. If unrelenting, ENT consultation would be advisable. CASE THREE: A 78-year-old woman presents with a several-day history of progressively worsening unilateral ear discomfort. She wears a hearing aid on that side. She has no history of ear trauma or infection; in fact, she prides herself on the clean state of her ears, maintained through regular swabbing with Q-tips. 3. Describe your clinical impression and therapeutic approach to a patient like this in each of the following scenarios: a. There are no other symptoms, and no other medical problems. There is no discomfort on retraction of the pinna. The ear canal is partially covered by some yellowish material with black dots. The tympanic membrane is dull, but otherwise unremarkable. The periauricular exam is normal. This patient has a mild otitis externa likely due to superficial fungal infection. Gentle removal of visible fluid/debris (accomplished in the generalist’s office with cotton swabs and/or irrigation) is recommended routinely in cases of otitis externa. In addition, topical application of acetic acid (e.g. VoSol), boric acid drops, Burow’s solution (aluminum acetate in water, an astringent) and alcohol rinses; and perhaps topical anti-fungal drops would be helpful here. b. There are no other symptoms, and no other medical problems. There is minimal discomfort on retraction of the pinna. The ear canal is erythematous along part of its circumference, with some flaky yellowgreen material along the inferior aspect, but a clear view of the tympanic membrane (dull but otherwise unremarkable). The periauricular exam is normal. This is a case of localized acute otitis externa, likely caused by bacterial superinfection. [Ask which pathogens are usually involved: answer=pseudomonas aeruginosa or staph aureus]. In addition to gentle removal of debris, mild cases like this may resolve with topical antibiotic/anti-inflammatory drops (e.g. Cortisporin, or Cipro-HC) alone. c. She has nasal congestion and a cough, but is otherwise healthy. There is minimal discomfort on retraction of the pinna. The ear is draining yellowish fluid that precludes adequate examination of the canal or tympanic membrane. The periauricular exam is normal. In the absence of visible canal inflammatory changes or significant pain on pinna retraction, a canal filled with purulent fluid may present confusion between otitis externa, and otitis media with tympanic membrane perforation. In the acute setting, the latter is sometimes associated with RELIEF of pain. But where differentiation is difficult, you may need to treat empirically for both. Historically, this was often done using a broad-spectrum oral antibiotic, e.g. amoxicillin-clavulanic acid or perhaps a respiratory-pathogen-effective quinolone. In recent years, it has become apparent that many topical (otic drops) antibiotics can be used safely (particularly the quinolones) even in the presence of a TM perforation (where the drops would wash into the middle ear compartment). d. As in (c), except that there is moderate pain on retraction of the pinna, which is not protruding at rest. The ear canal is swollen and erythematous for the short distance that is visualizable before the lumen is blocked by wet yellowish curdlike material in the lumen. A case of diffuse acute otitis externa. In addition to superficial aspiration/swabbing to remove visible purulent material, instillation of topical antibiotic/anti-inflammatory drops using indwelling cotton wicks may be necessary to penetrate the medial aspect of the canal. Oral antibiotics effective against the likely pathogens [again, (staph aureus and pseudomonas most frequently) may be needed, such as quinolones. Close follow-up, within 1-2 days initially, would be important to ensure response/resolution. e. As in (d), but the patient has severe pain and a fever, and has underlying diabetes mellitus. No discussion of adult infectious ear problems would be complete without mention of necrotizing (“malignant”) otitis externa, an uncommon but very serious infectious (not neoplastic!) complication to which patients with diabetes or other immunosuppressive conditions are more susceptible. Other worrisome features might include red granulation tissue visible in the canal, extension of cellulitis onto the auricle, and/or an ipsilateral facial nerve palsy. A more aggressive approach is required for necrotizing OE- the patient should be hospitalized, parenteral antibiotics initiated [same pathogens as in diffuse OE]; and otolaryngology consulted emergently. 4. What advice would you give to a patient to prevent otitis externa? Practices or activities in adults that predispose to otitis externa include: a. Foreign-body insertion, esp. cotton-tipped swabs for cleaning the ear (disrupts the ear’s usual self-cleansing mechanisms, pushes debris deeper, and can abrade the delicate skin lining the canal). This practice should be discouraged in everyone! b. Frequent swimming (hence the common lay term “swimmer’s ear”). Swimmers should ensure adequate drying of the ear canal afterwards. This may be accomplished with alcohol drops. Some have also used hair blow dryers. c. Usage of a hearing aid. These may need to be removed when not in use. CASE FOUR: A 49-year-old woman presents with several weeks of malodorous, unilateral ear drainage that has not improved despite treatment with a course of amoxicillin and a course of cefaclor, prescribed at two different walk-in clinic visits. Ear exam is notable for normal external structures, absence of pain on pinna retraction, but inability to view into the canal because of purulent fluid. 5. Describe your clinical impression and plan. This description suggests chronic suppurative otitis media. This is usually associated with a non-healing TM perforation. In addition to involvement of a different spectrum of bacteria (including aerobes, anaerobes, non-respiratory gram negatives), there may be an underlying cholesteatoma (a non-malignant but locally invasive/destructive squamous epithelial overgrowth that can cause permanent damage/hearing loss). Topical antibiotics similar to those discussed in Case 3c. (quinolones) could be tried. However, ENT consultation would also be prudent. CASE FIVE – EXTRA CREDIT: A previously healthy 65-year-old man presents with lancinating right ear pain for the past two days. He feels like his speech is slightly slurred, his tongue and ipsilateral eye feel “funny.” He has a mild right facial droop, and vesicles in the right ear canal, which is otherwise unremarkable. 6. What does this patient have? A case of Ramsay-Hunt syndrome, i.e. herpes zoster oticus, from “shingles” in the distribution of cranial nerve VII, giving rise to a peripheral facial nerve palsy. Specifics of treatment (e.g. acyclovir +/or steroids +/or surgical decompression) have been controversial. However, in view of the substantial rate of permanent deficit, it may be prudent to consult otolaryngology. References: rd 1. Otologic Infections.Textbook of Primary Care Medicine, 3 edition. John Noble MD (Editor-in-chief). Mosby, 2001:1731- 1736. 2. Glasziou, PP. Del Mar, CB. Sanders, SL. Hayem, M. Antibiotics for acute otitis media in children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2004;3. Additional References: 1. Otitis Externa. Up-To-Date. Dec.3, 2004. 2. Also worth consulting “on the fly” in clinic are the chapters in Barker’s Principles of Ambulatory Medicine, 6th edition, and Goroll’s Primary Care Medicine textbook.