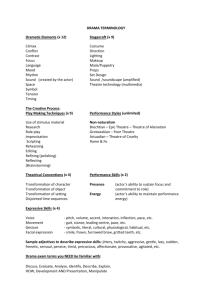

ISS research paper template

advertisement