Name Changes of the Revolution

advertisement

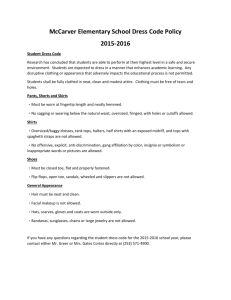

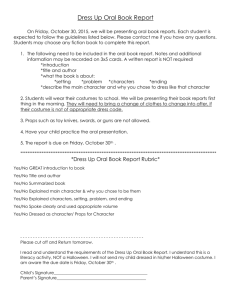

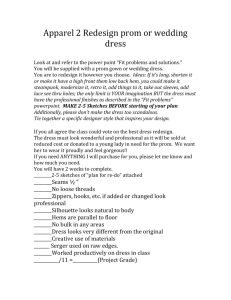

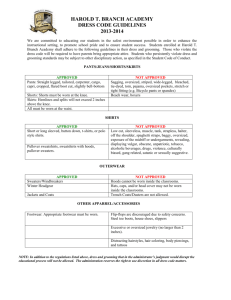

Name Changes of the Revolution During the Reign of Terror under the National Convention, the French language changed. To eradicate any traces of the Old Regime: ties to the monarchy, remnants of the social inequities of the feudal Estate System, and the restrictive control of the Catholic Church, certain words were banned and objects, places, and people renamed to reflect the ideals of the French Revolution’s slogan, Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity. People were no longer called monsieur or madame, but now became citoyen or “citizen”. People changed their names. Leroys meaning “kings” now became Laloys meaning “laws”. One enthusiastic Jacobin named his child Libre Constitution Letruc or “Free Constitution Letruc”. King Louis XVI’s cousin, the Duke of Orleans changed his last name to Equality to show his allegiance was to the Revolution. Street names changed in a similar way. Place Louis XV became Place de la Revolution. The Street of the Crown became the Street of the Nations. The word “king” was strictly forbidden. There was even an attempt to retitle the “queen bee” into the more revolutionary “laying bee”. The face cards of playing cards were changed from king, queen, and jack to liberty, equality, and fraternity. And there was a new sick fascination with the guillotine that was behind the development of national jokes, fashion trends, and even new toys. Here is a story to show you the effects of the name changes: “A merchant from a town in a remote province, arrived in Paris on business, said to the porter of his hotel: ‘Monsieur, can you direct me to the Rue Princesse?” The porter scowled suspiciously. ‘You had better be careful how you speak, citizen?” ‘What do you mean”, replied the merchant. The porter replied, “Don’t you know the law forbids the use of the titles monsieur and madame---or mademoiselle? We are all citizens and citizenesses now. If you were overheard, you might be suspected as an enemy of the Revolution.’ The merchant responded with, ‘Ah! I did not know, mons-er-citizen. Is this something new?’ The porter looked at him in surprise and then explained, ‘The National Convention has recently enacted it, but ignorance of the law will not excuse you before the Revolutionary Tribunal, citizen. There are those who have sneezed in the basket for less.’ The merchant was puzzled by the sneezed in the basket statement. He asked, ‘Sneezed in the basket…I do not understand.’ The porter laughed and said, ‘A little joke, citizen. It is said of those who have met our National Razor, the guillotine-or as some say, those who have fallen into the cat trap and have been patriotically shortened.’ And the porter chuckled once again. The merchant, now very concerned, said, ‘I see…and can you now direct me to the Rue Princesse?’ The porter shook his head and replied, “You will not find it, citizen. Our streets are no longer dishonored by the names of royalty, nobility, or the saints of the accursed Church of Rome. The street you mention is now the Rue Revolutionnaire (Revolutionary Street), near the university.’ As the merchant traveled about Paris, he would often have to ask directions, since Place Vendome (Vendome Square), named for a noble family of France, had become Place des Piques (Square of Pikes). The Rue Saint-Louis-en Ile (St. Louis Street on the Il de la Cite) was now the Rue de la Fraternite (Brotherhood Street). Even the Palais Royal had been renamed the Palais Egalite (Palace of Equality). Once again, everyone appeared to be gay and carefree, despite the tumbrels that roller through the streets every day. In October, fifty men and women went to the scaffold, fifty-eight in November, sixty-nine in December. The guillotine had become a sort of shrine at which the people worshipped, and the Place de la Revolution was a center of amusement more popular than the Palais Egalite. The guillotine now competed with the Bastille as an ornament. One could buy snuffboxes with little guillotines embossed on them, and metal dies to impress the guillotine on the wax used for sealing letters. Ladies wore jeweled guillotines and guillotine earrings. There was even a guillotine game in which children lopped off the heads of their dolls. When the carts turned into the Rue Nationale, once the Rue Royale, the doomed ones could see the Place de la Revolution, filled with a crowd whose red caps made it look like a field of poppies stirring in the wind. Many of the people had been waiting for hours in order to have a good spot, reading their newspapers, refreshing themselves with food and drink at stands put up there. Children frolicked, chasing each other like scampering squirrels. Peddlers wove in and out, crying ‘Little cake! Nice little cakes.’ It was like a circus day. A lane had been cleared for the tumbrels. As they drew near, their occupants looked up in terror at the high platform with its glittering instrument of death. There stood the ruffian, Sanson, whom some called the Butcher, though to his face they said he was the Avenger of the People. This was the official name for the executioner. There stood his assistant, a true showman, with a rose clenched between his teeth. The tumbrels moved up…halted…moved up. Their cargo, discharged, ascended the steps, some bravely, some assisted to keep from collapsing. The triangular knife rose…fell…rose…fell with monotonous regularity, and in rhythm with a cadence of a sound that rose and fell like the crash of the breakers on a rocky shore. One day of the Terror…How long would it last…how long could this bloody nightmare go on, in which no man was safe and no one knew when his turn would come? It would not end until 40,000 people lost their lives to the guillotine, and the people would be ready to return to a normalcy and stability. Revolutionary Fashions During the Revolution, trends in fashion inspired by the Enlightenment in the 1770s and 1780s, long before the fall of the Bastille, developed and were modified to meet the goal of democratization of dress. This was a revolutionary concept. By 1790, women has largely abandoned panniers (skirt hoops), and most of the padding that build out their rumps. A simple loose-waisted gown in white muslin or other light fabric was the most fashionable garment and were flatter. Natural curls replaced the elaborate, towering coiffures of the Old Regime. Men wore plain, close-fitting suits regardless of class or occasion. These fashions owed much to England where polite society was dominated by the landed gentry, whose concern with rural and domestic pursuits had encouraged the development of more practical and country-inspired clothing as early as the 1750s. In the 1780s, for ordinary day wear, the French man of fashion also adopted a plain frock or riding coat, short waistcoat, and high leather books, in imitation of his English counterpart. “A l’anglaise’ became synonymous with chic. After the overthrow of the monarchy in 1792, court dress was suppressed until Napoleon’s rise to power. Hair powder was left off soon after 1790. Although Robespierre never dropped the fashion, powdered wigs came to be regarded as symbols of the aristocracy. Powdering, in general, was anti-social; flour could be used to feed the people not to color wigs. Simplicity in dress became an expression of progressive politics, and erstwhile reactionaries tempered what they wore with a judicious sobriety. The use of national colors of red, white, and blue added a contemporary note. Patriots devised blue suits trimmed with red and white. They wore coat-buttons decorated with patriotic images. In 1793, the Committee of Public Safety invited the painter, David, to apply his artistic talents to patriotic propaganda dress. David made recommended improvements to the national dress to make it more appropriate to the ideas of the new republic and character of the Revolution. He suggested uniforms based on the classic tunics and togas from the Roman Republic for all state officials and citizens. But despite the enthusiasm for the toga idea by a few other artists, the costume remained a political fancy. But nearly everybody was expected to wear something in the colors of red, white, and blue. In Paris, the carefully negligent air of the Englishman’s country dress developed into deliberate scruffiness and “sick humor’ prevailed. A red ribbon around the throat or a “ceinture a la Victime” in reference to all the beheadings by the guillotine was too funny for words. Or people cropped their hair short to resemble the shorn heads of those condemned to the guillotine. The celebratory atmosphere of the Reign of Terror gave way to a number of frivolous and gruesome fashions and pastimes. One was the Victim’s Ball. In order to qualify for admittance to one of these soirees, one had to be a close relative or spouse of one who had lost their life under the blade of the guillotine. Invitations were so coveted that papers proving your right to attend had to be shown at the door, and some were even known to forge this certificate in their eagerness to attend. All the rage at these grand balls was to have the hair swept high off the neck, in imitation of “le toilette du condamne” where the victim’s hair is cut to make way for the kiss of the blade. Women’s dress began to reflect the contemporary taste for the antique, back to the ancient Greeks and Romans. Women wore white robes. Their bodies were revealed in a manner unknown for centuries, and for a short time, they enjoyed freedom of movement. This reflected new freedoms provided to the people by the National Convention. Jewelry was frowned upon, because it indicated wealth. Before the Revolution, French aristocrats had worn knee-breeches. Now revolutionaries wore the full-length trousers of the sans-culottes. The red liberty cap was very popular. The Scottish physician, John Moore, who had been visiting Paris wrote home describing the changes in the fashion mores that the Declaration of the Republic brought on. He wrote: “There is in Paris at present a great affectation of what plainness in dress, and simplicity of expression, which are supposed to belong to republicans. I have sometimes been in the company, since I came last to Paris, of a young man belonging to one of the first families in France who, contrary to the wishes of his relations, is a violent democrat. He came into my box last night at the playhouse; he was in boots, his hair cropped, and his whole dress slovenly; on this being taken notice of, he said that he was accustoming himself to appear like a republican. It reminded me of a very ugly man for her lover, said, “It is in order to get used to the ugliness of my husband.” “People are saying “tu” or thou to each other. They have substituted the name Citizen for Monsieur, when talking to or of any person; but more frequently, particularly in the National Convention, they simply use their name like Buzot, Guadet, Vergniaud. It has even been proposed in some of the newspapers that the custom of taking off the hat and bowing the head should be abolished, as remains of the ancient slavery. and unbecoming the independent spirit of free men; instead of which they are desired, on meeting their acquaintance in the street, to place their right hand on their heart as a sign of cordiality. David, the celebrated painter, who is a member of the National Convention and a zealous republican, has sketched some designs for a republican dress, which he seems eager to have introduced.” French Revolution ( Originally Published 1926 ) With the rise of the people against the house of Bourbon, we find many changes in France, and their influence was felt through many countries. On 14th of July , 1789, the Parisians made open display of their demands in the streets oftheir city and gave the signal for the fall of a whole social system by their attack on the Bastile. Extravagance in architecture, furniture,costume and mode of living at its height, all this was to be done away with, and a period ofthe strictest simplicity was to follow. Titles were dropped by all of the upper class who survived the guillotine, and men and woman were addressedas citizen and citizeness.One of the first acts of the General Assembly was the abolition by solemn decree of all distinction in dresses of the classes. Materials.—The manner of living was also simplified, but this unfortunately lasted but a short time. Simplicity was the key-note in costume, and dark colors and cheaper materials, especially cotton, were taking the place of the silks, velvets, ribbons, and laces of the former reigns. Fashion still mirrored the events of the times, both in the names of materials and the articles of apparel; the whole theory of it was based on the assumption of equality in dress; "all classes were mingling, willingly or unwillingly, through love or fear; and many wealthy persons rigidly adopted the simple attire." ' The tricolor, or the national cockade, appeared on every costume, as it was exceedingly dangerous to be seen without it in the days when one government succeeded another in such rapid succession. Women's Dress.—Women were too busy or too poor to take the trouble to change fashions as often as had been the case in former years, so we find little or no change taking place between 1789 and 1793. Straight lines had taken the place of panniers a few years before, and a masculine type of dress, borrowed from the English, had been the result. Now women were looking for comfort as well as simplicity, and had given up the stiff stays that were necessary when wearing the pointed waist and the pannier. Gowns were made with bodices cut short in the waist and with sleeves to the elbow ; the neck was low and still finished with the fichu; the skirt hung plain and straight from the high waistline, the hoop or vertugadine having gone the way of the pannier. Little or no trimming was used, except an occasional ruffle at the edge of the skirt. The cotton materials were printed with the national trophies and revolutionary symbols, or with red, white, and blue stripes, and a bunch of tricolored flowers placed at the left side above the heart showed the wearer's patriotism. In 1791 shops were established in Paris where ready-to-wear clothing might be purchased. The best known of these were run by Quenin, who supplied the men, and Mme. Teillard, who catered to the wants of the women. Printed lists of prices were sent out by both of these shops. Head-dresses.—The style of hair-dressing also under went a change, and instead of the huge piles that had been in vogue a short time before, the hair was worn low in front and hung in clusters of curls behind. Powder had gone with Costume of the period of the French Revolution, 1790. The other symbols of aristocracy, and for the first time in years the hair showed its natural color. Straw bonnets with high crowns and large flaring brims were used for a while; they were remnants of the huge, overtrimmed hats of the time of Louis XVI, and soon disappeared, to be followed by lace and muslin caps, the most popular of these being the mob-cap, with a deep lace ruffle around the face and neck, now known as the "Charlotte Corday " ; this was ornamented with the tricolored cockade or rosette. Men's Dress.—The Revolution brought about the greatest change in the costume of the men. Dark colors, generally black, were in evidence, and cloth and leather took the place of silk and velvet. All furbelows, ruffles, laces, and ribbons had disappeared, they being considered aristocratic and not suitable to the dress of a democratic citizen. The breeches lengthened until they reached the ankle, a style borrowed from the English sailors, or, as Calthrop declares, invented by Beau Brummel for common wear. This, of course, is not the first time that long trousers, or pantaloons, as they were called, were worn. They were considered a mark of the barbarian by the Romans, and were worn by the early Asiatics and the Persians, but they now became the forerunner of the modern plain dress for men ; for while the knee-breeches returned for formal dress and are still worn in England for court dress, the long trouser was used for informal dress and went through many changes until it finally reached its present style. The name pantaloon was first used as a term of derision or ridicule; it came from the character of Pantaloon, a clown, familiar to the readers of Italian comedies of the seventeenth century. For many years after the introduction of pantaloons they fitted very snugly to the figure, and were generally buttoned above the ankle. The style of coats had not changed except in the material and color. They were cut away in front at a rather high waistline, and had a narrow tail at the back with the plaits pressed flat from the waist; they closed in front with four or five large buttons. The collar was high, and turned over squarely where it met the large revers. A waistcoat of fancy material, also buttoned and a trifle longer than the coat in front, was open at the neck, where it showed the white stock collar and small cravat of lace. The cuff had gone and several small buttons closed the sleeve at the wrist. Head-dresses.—In England the powdered wig was still worn, but France seems to have discarded it with the rest of her aristocratic paraphernalia, and hair in the natural color prevailed, sometimes short, and sometimes long and tied behind in a queue. Black felt hats, turned up in the front, and ornamented with the tricolor cockade, were worn by all men, young and old, of high and low estate. Foot-gear.—High leather boots with close turn-over tops, generally made of a different colored leather, came up over the long, tight pantaloons, the heels were rather low, and the toes square.