GAS CHROMATOGRAPHY - Pace University Webspace

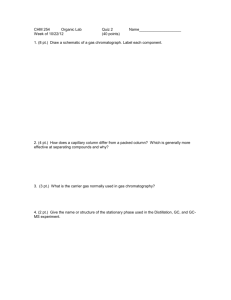

advertisement

Chapter 26 & 27 Introduction to Chromatographic Separations and Gas Chromatography The concept of Gas-Liquid Chromatography was first proposed in 1941 by Martin and Synge, who jointly were responsible for the development of liquid-liquid partition chromatography. More then a decade passed before the true advantages of Gas-liquid chromatography were demonstrated experimentally. Three years later in 1955 the first commercial apparatus for GLS appeared in the market. Ever since its first introduction, the growth and improvement in techniques, instrumentation and application has been phenomenal. Chromatography is an analytical method that is widely used for the separation, identification and determination of chemical components in a complex mixture. No other separation method is as powerful and generally applicable as chromatography. There are numerous chromatography techniques, however they have in common the use of a stationary phase and mobile phase. Components of a mixture are carried through the stationary phase by a flow of a gaseous or liquid mobile phase, separations being based on the differences in migration rates among the sample components. In contrast to most other types of chromatography the mobile phase does not interact with molecules of the analyte, its only function is to transport the analyte through the column. There are two types of Gas Chromatography, Gas Solid Chromatography (GSC) and Gas Liquid Chromatography (GLC). This site is mainly devoted to Gas Liquid Chromatography In gas chromatography (GC), the sample is vaporized and injected onto the head of a chromatographic column. Elution is brought about by the flow of an inert gaseous mobile phase. In contrast to most other types of chromatography, the mobile phase does not interact with molecules of the analyte; its only function is to transport the analyte through the column. Gas liquid chromatography is based upon the partition of analyte between a gaseous mobile phase and a liquid phase immobilized on the surface of an inert solid. The concept of gas-liquid chromatography was first enunciated in 1941 by Martin and Synge. Principles of Gas-Liquid Chromatography Retention Volumes: To take into account the effects of pressure and temperature in gas chromatography, it useful to use the retention volumes. The specific retention volume, Vg is defined as follows: Vg JF (t r t m ) 273 W Tc where, J = the pressure drop factor, F = average flow rate, tr and tm = retention times W = mass of stationary phase and Tc = column temperature in Kelvin. Instruments for GC The schematic of a gas chromatograph is shown below: Carrier Gas Supply Carrier gases, which must be chemically inert, include helium, argon, nitrogen, carbon dioxide, and hydrogen. The choice of gases is often dictated by the detector used. Associated with the gas supply are pressure regulators, gauges, and flow meters. In addition, the carrier gas system often contains a molecular sieve to remove water or other impurities. Flow rates are normally controlled by a two-stage pressure regulator at the gas cylinder and some sort of pressure regulator or flow regulator mounted in the chromatograph. Inlet pressures usually range from 10 to 50 psi, which lead to flow rates of 25 to 150 mL/min with packed columns and 1 to 25 mL/min for open-tubular columns. Flow rates can be established using a soap-bubble meter. Sample Injection System: Column efficiency requires that the sample be of suitable size and be introduced as a plug of vapor; slow injection of oversized samples causes band spreading and poor resolution. The most common method of injection involves the use of a micro-syringe to inject a liquid or gaseous sample through a silicone rubber diaphragm or septum into a flash vaporizer port located at the head of the column. For ordinary analytical columns, sample sizes vary from a few tenths of a microliter to 20microliters. Capillary columns require much smaller samples (~0.001microliters) Column Configurations and Column Ovens: Two general types of columns are encountered in gas chromatography, packed and open tubular, or capillary. To date, the vast majority of gas chromatography has been carried out on packed columns. Chromatographic columns vary in length from less than 2m to 50m or more. They are constructed of stainless steel, glass, fused silica, or Teflon. In order to fit into and oven for thermostating, they are usually formed as coils having diameters of 10 to 30cm. Column temperature is an important variable that must be controlled to a few tenths of a degree for precise work, so the column is ordinarily housed in a thermostatted oven. The optimum column temperature depends upon the boiling point of the sample and the degree of separation required. Roughly, a temperature equal to or slightly above the average boiling point of a sample results in a reasonable elution time. For samples with a broad boiling range, it is often desirable to employ temperature programming, whereby the column temperature is increased either continuously or in steps as separation proceeds. The figure below shows the improvement brought about by temperature programming. In general, optimum resolution is associated with minimal temperature; the cost of lowered temperature, however, is an increase in elution time and therefore the time required to complete an analysis. Detectors Characteristics Of The Ideal Detector: 1. Adequate sensitivity. 2. Good stability and reproducibility. 3. A linear response to analyses that extends over several orders of magnitude. 4. A temperature range from room temperature to at least 400degC. 5. A short response time that is independent of flow rate. 6. High reliability and ease of use. 7. Similarity in response toward all analyses. 8. Nondestructive of sample. Flame Ionization Detector: The flame ionization detector (FID) is one of the most widely used and generally applicable detectors for gas chromatography. The effluent from the column is mixed with hydrogen and air and then ignited electrically. Most organic compounds, when pyrolyzed at the temperature of a hydrogen/air flame, produce ions and electrons that can conduct electricity through the flame. A potential of a few hundred volts is applied across the burner tip and a collector electrode is located above the flame. The resulting current is then directed into a high impedance operational amplifier for measurement. Functional groups such as carbonyl, alcohol, halogen, and amine, yield fewer ions or none at all in a flame. In addition, the detector is insensitive toward noncombustible gases such as H2O, CO2, SO2, and NOx. These properties make the flame ionization detector a most useful general detector for the analysis of most organic samples, including those that are contaminated with water and oxides of nitrogen and sulfur. The flame ionization detector exhibits a high sensitivity, large linear response range, and low noise. It is generally rugged and easy to use. A disadvantage of this detector is that it destroys the sample. A diagram of a typical FID is shown in below. Thermal Conductivity Detector: A very early detector for gas chromatography is based upon changes in the thermal conductivity of the gas stream brought about by the presence of analyte molecules. This device is sometimes called a katharometer. The sensing element of a katharometer is an electrically heated element whose temperature at constant electrical power depends upon the thermal conductivity of the surrounding gas. The heated element may be a fine platinum, gold or tungsten wire or, alternatively, a semiconducting resistor. The advantage of the thermal conductivity detector is its simplicity, its large linear range, its general response to both organic and inorganic species, and its nondestructive character. A limitation of the katharometer is its relatively low sensitivity. Thermoionic Detector: The thermoionic detector (TID) is selective toward organic compounds containing phosphorous and nitrogen. It is similar in structure to the flame detector. Electron-Capture Detector: Electron-capture detector (ECD) operates in much the same way as a proportional counter for measurement of X-radiation. Here the effluent from the column passes over a beta-emitter, such as nickel-63 or tritium (adsorbed on platinum or titanium foil). An electron from the emitter causes ionization of the carrier gas (often nitrogen) and the production of a burst of electrons. In the absence of organic species, a constant standing current between a pair of electrodes results from this ionization process. The current decreases however in the presence of those organic molecules that tend to capture electrons. The electron-capture detector is selective in its response, being highly sensitive toward molecules that contain electronegative functional groups such as halogens, peroxides, quinones, and nitro groups. Electron-capture detectors are highly sensitive and possesses the advantage of not altering the sample significantly. On the other hand, their linear response range is usually limited to about two orders of magnitude. Atomic Emission Detector (AED): The newest commercially available gaschromatographic detector is based upon atomic emission. In this device, the eluent is introduced into a microwaveenergized helium plasma that is coupled to a diode-array optical emission spectrometer. The plasma is sufficiently energetic to atomize all of the elements in a sample and to excite their characteristic atomic emission spectra. GC COLUMNS AND STATIONARY PHASE Packed Columns: Present day packed columns are fabricated from glass, metal (stainless steel, copper, aluminum), or Teflon tubes that typically have lengths of 2 to 3 m and inside diameters of 2 to 4mm. These tubes are densely packed with a uniform, finely divided packing material, or solid support, that is coated with a thin layer of stationary liquid phase. The tubes are formed as coils having diameters of roughly 15cm. Solid Support Materials: The solid support in a packed column serves to hold the stationary phase in place so that as large a surface area as possible is exposed to the mobile phase. The ideal support consists of small, uniform spherical particles with good mechanical strength and a specific surface area of at least 1m/g. In addition, the material should be inert at elevated temperatures and be uniformly wetted by the liquid phase. Particle Size Supports: The efficiency of a gas-chromatographic column increases rapidly with decreasing particle diameter of the packing. The pressure difference required to maintain a given flow rate of carrier gas, however, varies inversely as the square of the particle diameter; the latter relationship has placed lower limits on the size of particles employed in gas chromatography, because it is not convenient to use pressure differences that are greater than about 50psi. Open Tubular Columns: Open tubular, or capillary, columns are of two basic types, namely, wall-coated open tubular (WCOT) and support-coated open tubular(SCOT). WCOT columns are simply capillary tubes coated with a thin layer of the stationary phase. In SCOT columns the inner surface of the capillary is lined with a thin film of a support material, such as diatomaceous earth. This type of column holds several times as much stationary phase as does a wall-coated column and thus has a greater sample capacity. ADSORPTION ON COLUMN PACKINGS OR CAPILLARY WALLS A problem that has plagued GC has been the physical adsorption of polar or polarizable analyte species such as alcohols or aromatic hydrocarbons, on the silicate surfaces of column packings or capillary walls. Adsorption results in distorted peaks, which are broadened and often exhibit a tail. It has been established that adsorption is the consequence of silanol groups that form on the surface of silicates by reaction with moisture. The SiOH groups on the support surface have a strong affinity for polar organic molecules and tend to retain them by adsorption. Support materials can be deactivated by silanization with dimethyl chlorosilane (DMCS). STATIONARY PHASE Desirable properties for the immobilized liquid phase in a gas liquid chromatographic column include: 1. low volatility 2. thermal stability 3. chemical inertness 4. solvent characteristics such that k’ and alpha values for the solutes to be resolved fall within a suitable range. Generally, the polarity of the stationary phase should match that of the sample components. Commonly used stationary phases are listed in below. Stationary Phase Polydimethyl siloxane Common Maximum Trade Name Temperature (C) OV-1, SE-30 350 Common Applications General-purpose nonpolar phase; hydrocarbons; polynuclear aromatics; drugs; steriods; PCBs Poly(phenylmethyldimethyl) OV-3, SE-52 350 siloxane (10% phenyl) Poly(phenylmethyl) siloxane Fatty acid methyl esters; alkaloids; drugs; halogenated compounds OV-17 250 Drugs; steriods; pesticides; glycols OV-210 200 Chlorinated aromatics; nitroaromatics; (50% phenyl) Poly(trifluoropropyldimethyl) siloxane Polyethylene glycol alkyl-substituted benzenes Carbowax 20M 250 Free acid; alcohol; ethers; essential oils; glycols Poly(dicyanoallyldimethyl) siloxane OV-275 240 Polyunsaturated fatty acids; rosin acids; free acids; alcohols Bonded and Cross-linked Stationary Phases: The purpose of bonding and cross-linking is to provide a longer-lasting stationary phase that can be rinsed with a solvent when the film becomes contaminated. With use, untreated columns slowly lose their stationary phase due to bleeding in which a small amount of immobilized liquid is carried out of the column during the elution process. Cross-linking is carried out in situ after a column is coated with one of the polymers listed in above Chiral Stationary Phases: There has been recent developments of stationary phases which can separate chiral compounds. One method is to form a derivative of the analyte with an optically active reagent that forms a pair of diasteromers that can be separated on an achiral column. The alternative method is to use a chiral liquid as the stationary phase. Film Thickness: Film thickness primarily affect the retentive character and the capacity of a column. Thick films are used with highly volatile analytes, because such films retain solutes for a longer time and thus provide a greater time for separation to take place. Thin films are useful for separating species of low volatility in a reasonable time. APPLICATIONS OF GC Qualitative Analysis Gas chromatographs are widely used as criteria for establishing the purity of organic compounds. Contaminants, if present, are revealed by the appearance of additional peaks. The Retention Index: The retention index, I, was first proposed by Kovats in 1958 as a parameter for identifying solutes from chromatograms. The retention index for any given solute can be derived from a chromatogram of a mixture of that solute with at least two normal alkanes having retention times that bracket that of the solute. That is, normal alkanes are the standards upon which the retention index scale is based. By definition, the retention index for a normal alkane is equal to 100 times the number of carbons in the compound regardless of the column packing, the temperature, or other chromatographic conditions. The retention index system has the advantage of being based upon readily available reference materials that cover a wide boiling range. Quantitative Analysis: The relative concentration of an analyte is proportional to the peak area obtained on the gas chromatogram. Thus the GC can be calibrated with several standards and a calibration curve is obtained, then the concentration of the unknown analyte can be determined using the peak area. INTERFACING GC WITH SPECTROSCOPIC METHODS When GC is coupled with other separation methods, both serve as a powerful tool for identifying the components of complex mixtures. A popular combination is GC/MS. This interface have been used for the identification of hundreds of components that are present in natural and biological systems. For example, these procedures have permitted characterization of the odor and flavor components of foods, identification of water pollutants, medical diagnosis based on breath components, and studies of drug metabolites. Another popular interface is that of GC/FTIR. Below is a diagram of GC/MS a instrument. GAS-SOLID CHROMATOGRAPHY Gas-solid chromatography is based upon absorption of gaseous substances on solid surfaces. Distribution coefficients are generally much larger than those for gas-liquid chromatography. Consequently, gas -solid chromatography is useful for the separation of species that are not retained by gas-liquid columns, such as the components of air, hydrogen sulfide, carbon disulfide, nitrogen oxides, and rare gases. Gas-solid chromatography is performed with both packed and open tubular columns. For the latter, a thin layer of adsorbent is affixed to the inner walls of the capillary. Such columns are sometimes called porous layer open tubular columns, or PLOT columns. Two types of adsorbents are molecular sieves and porous polymers. Molecular Sieves: Molecular sieves are aluminum silicate ion exchangers, whose pore size depends upon the kind of cation present. The sieves are classified according to the maximum diameter of molecules that can enter the pores. Commercial molecular sieves come in pore sizes of 4, 5, 10, and 13 angstroms. Molecular sieves can be used to separate small molecules from large. Porous Polymers: Porous polymer beads of uniform size are manufactured from styrene cross-linked with divinylbenzene. The pore size of these beads is uniform and is controlled by the amount of cross-linking. Porous polymers have found considerable use in the separation of gaseous polar species such as hydrogen sulfide, oxides of nitrogen, water, carbon dioxide, methanol, and vinyl chloride. Important Terms to Know: Stationary phase The stationary phase consists of the support, which is either a porous small-particle material for packed columns or the inner walls of a glass or fussed-silica capillary column. The stationary liquid is either fixed merely by adhesion or by chemical bonding in order to produce a homogeneous coating. Mobile phase. In GC an inert gas e.g. He N2 H2 acts as the mobile phase, which effects the transport of the solutes through the column. Elution By transportation in the mobile phase the solutes migrate with a velocity through the separation column which depends on the partition coefficients of the solutes between the given stationary phase and mobile phase. Solutes Sample components that are being separated. Detector The detector generates a continuously recorded electrical signal during the chromatographic separation, which is proportional to the concentration of the separated solute in the mobile phase. There are universal and specific types of detectors. Chromatograph y A term for methods of separation based upon the partition of analyte species between a stationary phase and mobile phase. Distribution constants, Partition coefficients An equilibrium constant for the distribution of a solute between two immiscible phases. Retention times The time between sample injection and arrival of the analyte peak at the detector. Gaussian Distribution A distribution in which small departures from a central result occur more frequently then large ones and in which positive a negative variation occur with equal frequency. GC Quiz Question The following data were obtained by gas-liquid chromatography on a 40cm packed column Compound Air Methylcyclohexane Methylcyclohexene Toluene TR min 1,9 10.0 1.09 13.4 Question 1 Calculate, 1a) the average number of plates from the data 1b) the standard deviation of the average in 1a 1c) the average plate height for the column Question 2 W½ min 0.76 0.82 1.06 Calculate the resolution for, 2a) Methylcyclohexene and Methylcyclohexane 2b) Methylcyclohexene and toluene 2c) Methylcyclohexane and toluene Question 3 If Cs and Cm for the column were 19.6 and 62.6 mL, respectively and a non retained air peak appeared after 1.9 min calculate the 3a) Retention factor for each of the three compounds 3b) Distribution constant for each of the three compounds 3c) Selectivity factor for methylcyclohexane and methylcyclohexene 3d) Selectivity factor for methylcyclohexene and toluene GC Quiz Answers 1a) N = 2.7 x 103 1b) s = 0.1 x 103 1c) H = 0.015cm 2a) 1.1 2b) 2.7 2c) 3.7 3a) k’1 = 4.3 k’2 = 4.7 k’3 = 6.1 3b) K1 = 14 K2 = 15 K3 = 19 3c) 1.11 3d) 1.28 References: www.shahid.ic24.net