HEALTHY PREGNANCY AND PREGNANCY CARE

advertisement

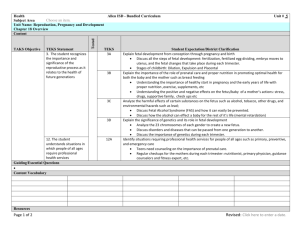

HEALTHY PREGNANCY AND PREGNANCY CARE Compiled and presented by Averille Morgan & Sue Baxter Health during pregnancy is a continuum of wellness and good function of body, mind and spirit. The lack of opportunity to obtain good food, rest, moderate activity, mental support, solitude etc may impact the maternal health in a negative sense. This may challenge her ability to self regulate towards a health she is used to or knows or expects for her pregnancy. Women in the UK have come to expect intervention for their pregnancy through health care, social and political support e.g. women are encouraged by the government to take up antenatal care by 12 weeks gestation, to receive free dietary supplements e.g. folic acid and, if of low income, receive income support. INTEGRATED SYSTEMS CHANGES DURING PREGNANCY As the uterus enlarges during pregnancy a change in the relative position of other organs occurs. The position of each organ is inter-dependent on the position of other organs, connective tissue etc. Physiological demands of pregnancy on the cardio-vascular, lymphatic, musculo-skeletal, nervous and hormonal systems, to name a few, effect the movement and function within and between specific tissue systems. For example: the renal system in pregnancy- the engorgement and growth of the endometrium in the first trimester stretches the anterior pubo-cervical ligaments superiorly and anteriorly. The bladder and urethra are pushed anteriorly and superiorly until the fundus moves above the pelvic brim in the second trimester. The peritoneal fascias and ileum are stretched anteriorly, the lower abdominal portions of the bowel (i.e. ileo-caecum, sigmoid colon) move superior- laterally. By the third trimester the anterior renal fascias are pulled superiorly and anteriorly with the large intestine, the posterior lamina are held taut with dilation of the renal hilus and vessels. The ureters dilate and take a more tortuous path along the psoas muscle. The venous return from the uterus, vagina, bladder and rectum meets gradually more resistance in the pelvis and dilates. The increased blood plasma levels places more demand on the glomerulus’s filtration rate increasing the extra cellular fluid potential. This leads to gradual tissue oedema. The skill of the therapist is to subtly, gently improve the integration of the maternal body systems by contacting health in the tissues and supporting the potential to be healthy. This means that finding a tissue or fluid fulcrum, for instance, which has potential to be healthy will enable self correction of the whole body system. NUTRITION, DIGESTION and SUPPLEMENTATION Let’s focus on the relationship of good nutrition (in a western based diet) with digestive function in maintaining a healthy environment for the mother and unborn child. The Food Standards Agency UK places emphasis on a diet which provides enough energy and nutrients for the maternal body to support the adequate growth of the unborn child. The suggestion include: Plenty of fruit and vegetables- at least 5 portions of a variety of fruit and vegetables a day (fresh, frozen, tinned or dried), a glass of juice Starchy foods such as bread, pasta, rice potatoes and pulses (e.g. beans, lentils, peas) Protein such as lean meat, chicken, fish, eggs and pulses Fibre by means of wholegrain bread and cereals, pasta, rice, pulses, fresh fruit and vegetables Dairy foods such as milk, cheese, yoghurt. Good nutrition can be described by isolating food groups such as dairy or protein or by specific nutrients, such as iron, calcium, fatty acids (such as omega 3 & 6), or menu planning (e.g. RDA for Vit E = 1 tbsp veg oil + 1 avocado) which brings foods together in a daily menu rich in folate, B6, B12 etc. Good digestion has a less public profile in terms of digestion which is improved by time and care over food preparation, time to eat, chewing slowly, resting after a meal, breathing well whilst eating. In what way is good nutrition accessible to each pregnant woman? For example; does a woman want or need to know about sources of iron or folic acid; OR does it make more sense to her to eat extra red meat, green vegetables and bread; OR she understands meal descriptions such as a portion of red meat, lentils or vegetables served with rice or pasta or wholegrain bread for 2 meals each day. Vitamins and minerals Also referred to as “micronutrients” this group acts as catalysts for enzyme action for digestion ie breakdown proteins to amino acids. Vitamins and minerals are therefore important to activate enzyme activity which is required to supply energy to the mother and fetus, boost immunity, build bones and teeth, balance hormones, support neural development etc. Vitamins and minerals are found in the food we eat, the soil in which our food is grown and in our water. Food which has been grown in rich mineral base soil (organic), prepared with little or no refinement or processing, little or no cooking of fresh fruit and vegetables will maintain a higher proportion of minerals and vitamins. The government sets a ‘recommended daily allowance’ (RDA) as a general guide for the mass population. So packaging standards then supply some of the RDA’s in their foodstuffs to help the consumer feel like she is making an informed decision on the nutrient level available to her in that product. (See Appendix A). However, absorption of the RDA of each vitamin or mineral requires a process of digestion in which a balance of the right enzymes, acids, alkaloids etc. will make the vitamin or mineral available for further tissue metabolism. For example, in order to utilise the ferrous iron in spinach or red meat the enzymic action needs to be coupled with Vitamin C and without high levels of calcium, caffeine or tannin. In other cases or bodies produce the vitamin, such as vitamin B12, which is stored in body fat and made by bacteria living in the intestinal tract. The production of vitamin B12 may be improved by supporting the gut bacterial activity with a balance in gut acidity/ alkalinity or supplementation of lactobacillus (e.g. natural yoghurt, pro-biotic drinks) or sprouted beans/seeds. (See Appendix B for vitamin and mineral rich foods during pregnancy). Are dietary supplements advisable during pregnancy? Holford & Lawson (2004) advocate dietary supplementation as they report that most British surveys since the 1980’s show that eating a balanced diet revealed lower levels of vitamins and minerals recommended by the government‘s RDA‘s. Holford & Lawson insist that during pregnancy a basic supplementation of folic acid, zinc, B12,B6 are essential for fetal CNS development. They assert that food production and preparation techniques, through mass farming and food packing, has contributed to a low nutrient food base. This means that even organic produce eaten within the week of harvesting will still be low in nutrients required by the pregnant and breast feeding mother. They suggest that a good diet will be deficient of optimum levels of vitamins and minerals and that supplements will counterbalance the deficiency. Holford & Lawson recommend three supplements: 1. A pregnancy multivitamin and mineral tablet/tonic 2. 1,000-2,000mg of extra Vitamin C 3. Omega 3 & 6 essential fatty acids (as fish or nut/seed oil). The main problems with supplementation is the increased risk of fetal toxicity from a too a high level of some vitamins (e.g. vitamins A & D) and minerals (Iodine & Iron). Makrides et al (2003) randomised, double-blind, placebo controlled study indicated that ferrous sulphate supplementation during pregnancy reduced the incidence of Iron Deficiency Anaemia and Iron Deficiency at delivery. They also noted no difference in gut irritability with the iron supplement. However, Roberts (2003) notes that it is the ferrous sulphate supplement which irritates intestinal linings and that ferrous succinate and ferrous fumarate supplements are more gut friendly (I.e ferrous succinate and fumarate are found in liquid tonics extracted from vegetables and fruits). Roberts also suggests that calcium supplements will decrease the iron uptake and vitamin C will increase iron uptake. Weight gain is healthy during pregnancy Different women gain different amounts of weight during the whole pregnancy from 10-12kg(22-28lbs). Maternal weight gain is strongly associated with birth size (Lagiou et al 2004) however, nutritional associations with weight gain are inconclusive. An association with increased weight gain from cholesterol is linked with maternal and fetal coronary heart disease. This may be seen as an unhealthy maternal weight gain during pregnancy, as is under nutrition and low weight gain during pregnancy, and may have secondary side effects on the fetus. Maternal diet and growth of her fetus Langley-Evans et al. (2003) report strong evidence, with animal studies, that a low protein diet adversely influences renal structure and cardiovascular function in the developing fetus. The study team noted that this programmed the fetus to later hypertension. However, they found that if protein was increased in the diet that fetal renal development corrected. Merialdi et al (2004) conducted a double-blind trial among 242 poor Peruvian pregnant woman, giving them at 10-16 week gestation a supplement containing 60mg FE, 250mcg folic acid with or without 25mg Zinc. The study showed that fetal femur diaphysis length was greater in the Zinc supplementation group. Over nutrition in the pregnant adolescent may be detrimental to the growing fetus. A British study (Wallace-2004) indicated that placental growth is impaired by over nutrition and maternal growth hormone is implicated in the growth restriction. Foods to avoid: 1)infection- e.g. high levels of listeria may be found in soft mould-ripened cheeses (e.g. blue vein, brie), pate, uncooked or undercooked ready meals; e.g. high levels of salmonella may be found in some raw eggs, raw meats, unwashed packed salads; 2)poisoning- e.g. too much Vitamin A is toxic to fetal development and can be avoided by not combining high dose multi-vitamin supplements or fish oil supplements; e.g. mercury poisoning via tuna, marlin, swordfish, shark can be avoided if less than 4 times a medium can of fish is eaten per week. 3) dehydration-e.g.drinking less than 300mg caffeine per day ie. 3 mugs of instant coffee, 4 cans of energy drink, 8 bars of chocolate, 6 cups of tea; e.g. only 1-2 units of alcohol per week i.e. one glass of wine or ½ pint beer. Drink more than 2 litres of clean water per day. DIGESTION DURING PREGNANCY- physiological changes The maternal physiological adaptation during pregnancy enables improved digestion and supporting maternal and fetal nutritional demands. Such digestive changes include: Maternal saliva becomes more acidic & increased amylase = CHO digestion Esophageal motility and sphincter control reduces = churning of food/ backwash of stomach contents Stomach hypo tonicity and reduced motility = longer transit time Stomach acidity reduced from increased eostrogen and placental histaminase = reduces histamine output and less immune attack on fetus in 1-2 trimester Increased gastric lipase = increased triglyceride uptake Increased pancreatic amylase and lipase for sugar and cholesterol uptake Increased pancreatic enzyme secretion for protein digestion in the small intestine Small intestine secretion of maltase and lactase for sucrose and lactose digestion Increased height of duodenal villi = increased absorption of Ca, AA’s, vitamins Small & large intestine increased absorption of micronutrients and water Liver production of enzymes, proteins, serum lipids and bilirubin= liver enlargement & itchy skin Large intestine slow transit and increased storage = increased water uptake. CHANGING MATERNAL PHYSIOLOGY Gastrointestinal changes during pregnancy Progesterone relaxes the cardiac sphincter of the stomach and smooth muscles in the wall of the oesophagus. This may allow for reflux of stomach contents and acid into the oesophagus giving symptoms of indigestion or heartburn as far as the back of the throat. With an enlarging uterus applying superior pressure on the diaphragm from 32-38 weeks, the pyloric sphincter action may be constricted. The slow emptying of the stomach and small intestine is effected by hormonal and physical displacement of the small intestine and may lead to nausea or vomiting. The small intestine, particularly the jejeno-ileum displaces superiorly and laterally to the left of the abdomen. The ileum is stretched anteriorly and inferiorly at the lower superficial portion of its pathway across the abdomen into the lower right quadrant. The enlarging uterus stretches the bowel mesenteries anteriorly and laterally. The ileo- caecum is displaced superiorly and laterally in the right lower abdominal quadrant, sometimes to be palpated superior to the right iliac crest. The increased sensitivity at the ileo-caecal junction may cause increased bowel urgency, with visceral- like spasm or diarrhoea. The large intestine is pushed towards the more lateral portions of the abdominal cavity during pregnancy. The hepatic and splenic flexures of the colon are stretched superiorly and laterally under the liver and spleen respectively. The lower portion of the sigmoid colon, rectum and anus are compressed in the pelvic space particularly at 10-16 weeks and from 36 weeks or when fetal decent fills the space below the pelvic brim. Again the slowing bowel motility, the enlarging uterine pressure and increased water absorption during pregnancy may lead to constipation. The practitioner may advise on increased water intake (2 litres minimum per day), small meals and often, a variety of carbohydrates and proteins and fibre, light exercise, limited amounts of heavy lifting (e.g. sit with the toddler!). HORMONAL CHANGES IN PREGNANCY Initially the corpus luteum increases the secretion of progesterone and oestrogen to the mother and fetus, and is then supported by the placenta. The placental hormones inhibit production of follicle stimulating, luteinising and growth hormones (from the anterior pituitary gland). Adrenocorticotrophic (ACTH) hormones increases, releasing more plasma cortisol from the adrenal gland so as to increase sugar levels in plasma and blood. The myometrium and decidua convert cortisone to cortisol, which may contribute to immunological protection for the fetus (Stables 2000). Oxytocin is released by the posterior pituitary during pregnancy but by 30 weeks the uterine cells become more sensitive to the hormone and may be felt as low frequency high pressure Braxton Hicks contractions. Oxytocin sensitivity of the uterus and higher quantities of oxytocin released stimulates uterine contractions. Cervical ripening requires an increase in oestrogen (increases vascularity), relaxin and prostaglandin levels prior to labour. The hormonal relationship with ligament laxity in pregnancy is well documented (Chamberlain 1991, Ostgaard et al 1993). The laxity and pliability of connective tissues including the spinal dura and central nervous system is less well understood. Oestrogens increase the level of vascular permeability and fluid congestion in pregnancy and may account for ear, nose and throat congestion and sensitivity. Moore’s (1997) study of 10 pregnant women reported that their cognitive ability alters for the worse with poor concentration and poor memory most significantly effected. This study does not clarify whether the cognitive changes are a result of hormonal influences on brain function and/ or a reduction of brain size. Progesterone aids in secretion of insulin (insulin levels double by the third trimester) and reduces peripheral insulin usage. This means that more glucose is available for uptake by the fetus. In later pregnancy more protein is broken down into amino acids and stored adipose fats are consumed for energy uptake by the mother. The maternal CNS is the main organ which continues to absorb available glucose. Other body systems in the pregnant woman produce energy from lipids (lypolysis). Lypolysis is stimulated by growth hormones or cortisol, oestrogens increase the level of plasma cortisol. Odent (2003a) refers to the "foetal ejection reflex" as a primitive physiologic function of the maternal body to expel the fetus. The reflex is a combination of contractions, dilation, movement, breathing and relaxation which supports the descent of the fetus and relaxation or spreading of the pelvis and pelvic floor. The sudden surges of adrenaline raise the contraction phases. Odent states that if the mother feels warm, safe, private and not observed or intervened in any way then the reflex is a gentle continuation of the birth process. She will push only when the reflex propels her to do so. Odent also considers that it is not necessarily the maternal position which is important but rather the maternal hormonal balance. However, he does note that hormonal release will influence maternal positions e.g. if the maternal adrenaline is low then the mother will choose to lay down. He describes that it is most important that the mother finds postures or positions which enables this hormone balance. He reports that the reflex is counterbalanced by a maternal need to be supported into an upwards position and that the thigh muscles be able to relax to support the relaxation of the perineum. Psychology of pregnancy Not only does the physical body of the fetus and the gametes for the next generation develop in utero, so to does the self structure, the way in which the baby will relate to the world, begins to develop in relationship to the environment within the womb, the mothers health, emotions and thought patterns all play a part in shaping the self structure of the fetus (Verney 2002, Odent 2002, Terry 2005). This way of relating to the world may, along with genetics be passed down and affect following generations. Being pregnant is a profound and life changing event and many women feel more emotional than usual(Raphael–leff 1991) Her body is changing and she is realising and preparing for the drastic changes physically, psychologicallymany women experience heightened levels of anxiety (eg Dragons & Christdoulou 1998,) that being pregnant brings with it. Stern (2005) talks about the mother’s need to transform and reorganise herself, shifting her sense of identity from daughter to mother, from wife to parent, from career to motherhood and from one generation to the next. Many factors will influence how she is feeling such as is the baby planned, or wanted, does it follow a miscarriage, is the baby wanted but coming at a difficult time, is the parents relationship stable, is there a history of disability in the family, her age, etc. etc. There is also the changes that are taking place, nausea, changing body shape, no longer fitting into clothes, leaving work, social life changing, needing more rest, etc. etc. This is a very special time in the woman’s life and to enable her to support and nurture the child she is carrying she needs to be nurtured and supported by those around her, her partner, her parents and close friends, her health care workers (Midwife, Osteopath, Dr) etc. The baby’s environment is its mother and the environment she is in therefore also plays a crucial role in the pregnancy and the development of the baby. (Verney 2002, Odent 2002) The more supportive her environment is the more she can concentrate on caring for herself and the baby. Studies show that even if the mother is under a lot of stress and she feels supported, the effects of stress is less damaging to both mother and baby. Mother-Baby Influences Mothers environment Family Friends Mother Physical Home Emotional Job Baby Mental Spiritual Pollution Rest/Relaxation Diet Exercise Verney (2003) suggests that there are 3 main ways in which the mother and her baby communicate, through transfer of molecular information, sensory feelings, and intuitively. Sensory communication Mothers naturally communicate with their babies by stroking their stomachs, talking, humming and singing to their babies. Fathers can also communicate in this way and begin to bond with the unborn child. Studies have shown that babies recognise the voices of those they heard frequently in the womb and are more easily soothed by them both during gestation and after birth. If the mother regularly relaxes to a piece of music, the baby becomes programmed to also relax to that same piece both during gestation and after birth. Singing the same nursery rhymes to the baby once they are born that they heard regularly in the womb will help them off to sleep much more easily. The baby communicates with its mother by kicking gently in play or more vigorously if agitated or uncomfortable. Mothers also report feeling their babies cry, hiccup, roll, stretch and stroke the uterus or cervix. Intuitive communication We have all experienced even if only on a subconscious level knowing when someone is staring at us. Many people have experiences where they just know they have to phone home only to find that someone they are close to is in trouble, or they just know that something has happened to there loved one. Or when the phone goes you know who it is, or you think about some one and they phone you. This intuitive communication is much stronger between mother and baby as the baby is in the mothers energetic and emotional field, the baby is bathed in the thoughts, intentions and feelings of their mother. These fields of intuitive communication can also hold the history of miscarriage and loss, whether the child is wanted or unwanted, if there are feelings of this being a good or bad time to be expecting, etc. etc. Terry (2005) and Verney (2002) suggest that the emotional and mental aspects of both the mother and father at conception and the mother within the first trimester set the emotional tone of the child for life. Jennifer Rosenberg (2001) acknowledges that while we cannot always avoid strong negative emotions in pregnancy there are ways to reduce the health effects of our reactions without diminishing those reactions. She suggests allowing yourself to cry, not to stifle the tears and to look for joy where ever you can. Dr Mindell (in Nick Owen 2002) suggests that we can either be the heroines or the victims of our life dramas. When we learn to go with the flow rather than resist it, the fear can turn into excitement and the pain into intensity. Molecular communication Genes provide the blue print for basic brain development and we now understand that the environment and emotions acts on these genes to turn the switches on and off regulating gene activity and therefore shaping the babies personality, skills and the circuitry of their brains. Free passage of information across the placenta is natures way of preparing the baby for the world they are about to enter, as are the other forms of communication and all are essential for the survival of the species. If the information is continual distress the baby shifts from growth to self protection, however if the information is loving and supportive the environment encourages the selection of genetic programmes that promote growth. Lake calls this the “umbilical affect”. Joy and love baths the growing brain in feel good endorphins and neurohormones such as oxytocin which promote a lifetime sense of wellbeing. Just as nutrients and oxygen cross the placenta so do the hormones and neurotransmitters of the mother. Noradrenaline, Adrenaline and Cortisol secreted by the pituitary gland and the adrenal cortex in the short term serve to aid adaptation and survival, but in long term exposure, both the mother and the growing baby are programmed to react in a fight or flight mode. Many studies have shown the effect of long term stress on the baby, and Mulder E, et al (2002) showed that highly stressed and anxious mothers have an increased risk of spontaneous abortion, preterm labour and mal formed or growth retarded baby. When these 3 pathways of communication are mostly positive and only occasionally veer to the negative the baby learns how to be with a changing environment, it is important and a necessary part of development that the fetus is exposed to this. However in prolonged cases of stress hormone exposure, negative intuitive and sensory communication “Transmarginal Stress” may result. This is a term Frank Lake (1980) used to describe when the baby is overwhelmed by stress and negative affects impinging from the mother and the wider field. Womb of Spirit IDEAL needs are satisfied between COPING unmet needs are bearable, the disparity not too difficult OPPOSITIONAL withdrawal, pushing away the sense of danger in order to survive TRANSMARGINAL STRESS pushed beyond limits, a loss of being itself is experienced, introjections, splitting off/dissociation, immobilisation and self destruction The coping mechanisms of the fetus, its way of interrelating to the world is set up in the womb. Our ability to manage stress or not may be a direct result of our experience in the womb. It’s as though our nervous system gets its regulatory point set up in the womb. Life stressors are many and varied throughout pregnancy and what may be manageable for one mother may be catastrophic for another. By assisting the mother to be as available to the fetus and as stress free as possible we can help maintain the balance at an ideal, coping level there by assisting both mother and fetus. How can we help? -Encourage mother to discuss her fears and concerns, how does she feel about the pregnancy, the timing, her relationship etc and if necessary refer her to the appropriate people. -Encourage mother to explore acknowledge and moderate them. her feelings and emotions, to -Encourage mother to moderate the stress in her life and encourage her system to relax with relaxation techniques such as deep breathing or self massage of tension points -Encourage mother to be more in touch with her changing body and the movements of the baby. -Encourage her to have time for herself everyday. Wirth (2001) talks about having regular fetal love breaks when the mother takes the time to relax and send loving thoughts to her baby. Curham (2002) suggests the mother makes a “feel good list” of things that make them feel good i.e. relaxing bath, reading, seeing friends etc. Curham also suggests the need to have some one to support them in each of the following areas – -Practically someone who will offer help with the daily chores such as cleaning, shopping, taking other children to school. -Educationally someone who can offer advice and information on parenting and childcare. -Socially a group or activity that brings them into contact with like minded people. -Emotionally someone they have a loving bond with in whom they trust and can confide. -Self-esteem someone who acknowledges their skills and abilities, who will praise them and make them feel good. -Encourage her to find out about her own birth and to work through any residual emotions. Owen (2002) and Odent (2002) suggest that the mother’s experience of her own gestation and birth will colour her experience of being pregnant and giving birth to her own child. Zichella et al (in Owen 2002) suggests that women have easier births if they know about there own birth. -Listen, reflect, empathise, reassure, encourage. Offering encouragement can make a huge difference. Let the mother know that you believe in them and their abilities. Sometimes all they need is a little reassurance that their feelings, emotions, changing body shape etc are normal. Once they have made a decision support them in it and don’t let your prejudices get in the way. You may think caesareans are only for emergencies, but if the woman and her Dr have decided that is the best way, then support them. In general it is best for the women who see you to decide for themselves what they want to do – people come to health professionals because they believe in them and often take their word as gospel so what we say and how we say it is very important. Encouraging communication Questions that begin with “how” and “what” tend to help people focus on the present, they open things up, they invite exploration and curiosity. Questions that invite us to be more present with our bodily experiences, with our emotions and with our thoughts can be very useful. -Closed questions call for one word or very brief answers and can help the person to focus and become more grounded in their body and environment, particularly helpful when some one is spiralling in stress or trauma. However they keep the focus narrow and you may want to open things up more. -Open questions help us to explore things and to open up our minds. They are a way of inviting others to relax and let go of any fixed views that may be getting in their way. It encourages them to tap into their creativity and suggests that there is more than one way of looking at things. Ask only one question at a time, more than one is confusing and people tend to only answer the last question. Be sensitive to whether your questions have been invited or are they too much or overwhelming? “Why” questions can invite people to defend or explain themselves and this can make them feel pushed away and not supported. These questions can also make them feel stupid or incompetent. What language can you use to enable the mother to be more embodied and present with herself and her unborn child. How might you encourage the client, given Verneys 3 modes of communication, to engage with and to relate to her fetus. PELVIC TYPES AND FETAL PRESENTATIONS Is it necessary for a pregnant woman to know her pelvic type and the possibilities of fetal movement and presentation? Is it useful for her manual therapist or midwife to understand the relationships between pelvic types and fetal presentation, if there are any? The repetitive use of ultrasound as a standard identification of fetal position, presentation, size for age etc. has added to the information parents request on their developing child. Would it be useful to provide parents with an antenatal education on pelvic shape / types and how this may influence fetal positioning? Midwifery teachers such as Sutton and Scott believe so. They consider that a knowledge of pelvic types will enable the midwife to prepare the pregnant woman with exercise or movements to support a reduction in back or pelvic pain and to support an optimal fetal positioning prior and during labour. The model I have proposed for an optimal fetal position is enhanced with a knowledge of pelvic types. Pelvic types In 1933 the Caldwell- Moloy Classification of pelvic types was developed using a series of radiographic plates of female pelvis’. The main criticism of the classification is that the plates relate to “western women”. Are they of Anglo-saxon, Afro-Caribbean etc. origin? Please note that these types are given as a general guide to boney shape and we look more closely at the possibilities of how these shapes may influence pelvic function during pregnancy and labour. Gynaecoid This is the most common pelvic type (about 50%) and easiest for the baby to enter and exit the pelvis. There is a “… rounded brim, a large anterior space to the transverse diameter, straight side walls, a well curved sacrum and shallow cavity, blunt ischial spines, a wide sciatic notch and a pubic arch of 90 degrees” (Myles 1989 p.19). This means the pelvic inlet allows for a large brim diameter (13cm), a large central pelvis rotation space (12cm) and a large outlet in the A-P plane (13cm). Sutton (2001) described that this woman has rounded looking hips and tends to swing her hips round as she walks. Due to a large pelvic brim the fetus may enter in anterior or posterior positions and will turn anterior if the mother remains active. The ischial spines are relatively blunt and the pubic symphysis forms a large anterior space for the fetus to turn in. Sutton considers that the gynaecoid shaped pelvis supports optimal fetal positioning and an easy delivery. Anthropoid Is about 25% of pelvis types and has “…a long, oval brim in which the anteroposterior is longer than the transverse. The side walls diverge and the sacrum is long and deeply concave. The ischial spines are not prominent and the sciatic notch is very wide, as is the sub-pelvic angle” (Myles 1989 p.20). The woman with this pelvic type tends to have broad shoulders, narrow hips, tall and slender. Sutton describes that the fetus will often enter the pelvic brim on the oblique diameter as the brim is deep in the A-P diameter and then tend to turn directly OA or OP. If the descent is posterior this may present the mother with deep lumbo-sacral pain. Once descended to the pelvic floor rotation is relatively straight forward. Android This pelvic type resembles the male pelvis and is observed in about 20% of western women. The brim is heart shaped, with “…a narrow fore-pelvis and a transverse diameter which is towards the back. The side walls converge, making it funnel shaped with a deep cavity and a straight sacrum. The ischial spines are prominent and the sciatic notch narrow. The pubic arch angle is less than 90 degrees” (Myles 1989 p.20). This pelvic type is seen in heavily built structures, the pelvis looking “square” from behind and the inner thigh tends to touch. This pelvic type may allow easy access into the pelvic brim but is difficult for descent laterally ( from prominent spines ) and interiorly (from an acute pubic angle). As the pelvic cavity descends as a funnel to the pelvic outlet an OP position is common and labour is slow. Changing positions in second stage is important and Sutton considers that this woman will need to push late second stage to enlarge the pelvic outlet. Platypelloid Is about 5% of pelvic types and is flat and kidney- shaped at the pelvic brim (A-P diameter is reduced). The side walls diverge, the sacrum is flat, the ischial spines are blunt and the sub-pubic angle wide. This pelvis looks very wide laterally and flat, narrow in the A-P. The fetus will tend to enter the pelvic brim posterior or laterally and may cause maternal back and pubic symphysis pain on descent. The first stage of labour may be prolonged and descent slow but once at the pelvic floor the increased turning space in the large pelvic outlet will enable a quick second stage (Sutton 2001). Odent (2003- Birth and Breastfeeding) proposed that it is not the shape of the maternal pelvis which influences the ability to deliver the fetus but rather the mother's knowledge that she was delivered without intervention and that her labour is reliant on her hormonal state. With increasing generations of mothers who were born by caesarian section, are these women less likely to deliver naturally? Does a natural birth experience influence the neurological or hormonal abilities in the female baby in such a way so as to influence her capability to deliver naturally herself one day? ABDOMINAL AND PELVIC MUSCULAR CHANGES DURING PREGNANCY The increased body mass, hormonal effects on muscular and ligament laxity and anterior positional change of the uterus during pregnancy demands a continuing postural adaptation by the pregnant woman. It could be considered that the more flexible the spinal and pelvic ligaments the better the postural adaptation. Bullock-Saxton (1999) reviewed physiotherapy literature on the postural changes associated with pregnancy and she concluded that there is an exaggeration of the lumbar and thoracic curves, that the lumbo-sacral (LS) angle does increase the increased LS angle is a result of either anterior pelvic tilt with the enlarging uterus or as a compensation for an anterior shift of the lumbar spine. multiparous woman showed a marked increase in the lumbar lordosis (particularly in the third trimester) and that the individual's non- pregnant spinal curves had a tendancy to exaggerate during pregnancy e.g. kypholordosis, swayback etc. The rectus abdominis, external oblique, internal oblique and transverse abdominis muscles all attach to the linea alba by their aponeurosis. The abdominal muscles lengthen during pregnancy and the linea alba fascia shears laterally (commonly separating centrally above and/or below the umbilicus, a diastasis). This means that the abdominal muscles are less able to provide the ususal abdominal cavity pressure and limited spinal stability may result. The transverse abdominis muscle has been reported to play an important role in most trunk movements (Richardson and Jull 1995). The transverse abdominis and internal oblique supports the anterior abdominal changes during pregnancy by means of its attachments to the thoracolumbar fascia. With the enlargening uterus and anterior pull on the abdominal wall, the attachment to the thoracolumbar fascia becomes an increasingly important stabiliser for the abdominal and pelvic areas. The deep lumbar musculature such as the multifidus muscles act with the transverse abdominis and pelvic floor muscles to maintain spinal and pelvic stability. Richardson and Jull consider that the controlled action of these muscles through pregnancy enables a neutral spine i.e. a limitation of hyperlordosis and sacral nutation. Musculature of the posterior abdominal wall contribute to the lumbar-pelvic stability throughout pregnancy and aid in the position and descent of the fetus. For example; the psoas muscle attaches from the posterior crus of the diaphragm, lumbar vertebrae L1-2 to the lesser trochanter of the femur. Contracture of the psoas muscle in pregnancy aids the anterior stabilisation of the lumbar spine and flexion and internal rotation of the hips. Spasm of the iliopsoas may become painful with irritation of the lumbar plexus passing through it or by the visceral drag created by the enlarging uterus. That is the ureters run antero-medially along the psoas, the abdominal aorta medial on the left side, and the kidneys, cecum, descending and small intestines also pass along the muscle with vascular and lymphatic channels. Positional displacement of these structures with the changing shape of the uterus may facilitate muscular spasm of the psoas muscle. Other postural muscles e.g. ilium, quadratus lumborum stabilise the posterior abdominal wall and posterior pelvis to complement the anterior abdominal and pelvic muscles. The Rhombus of Michaelis is the kite shaped area of the lower three lumbar segments and the sacral promontory. The flexibility of this area is important for the descent of the fetal cranium or pelvis into the maternal pelvic brim and cavity. The increased lumbar lordosis in late pregnancy allows for an increase in the pelvic brim diameter. During second stage of labour the sacral promontory pushes posteriorly and the ilia spread laterally. In effect the rhombus stretches “opening the back” of the labouring mother. This increases the pelvic floor diameters laterally and enables a dextro-rotation and side bending left of the uterus (Sutton 2001). INTEGRITY OF UTERINE LIGAMENTS AND THE PELVIC FLOOR The pelvic floor musculature (PFM) in pregnancy and labour supports the pelvic organs, raises the intra-abdominal pressure, maintains urethral closure and the anorectal angle, assists in pelvic and spinal stability and the passage of the fetus in delivery. In order to understand the pelvic floor (PF) function a working anatomy is necessary. The pelvic floor consists of: Superficial perineal muscles and attachments Perineal body: is a fibromuscular cross over point in the middle of the perineum between the anus and vagina. Tearing of fibromuscular tissues during childbirth compromises the perineal body stability ( and may lead to urethral, anal and /or vaginal dysfunction). External Anal Sphincter: attaches to the skin, anus, coccyx, perineal body and puborectalis muscle. It maintains closure of anus taking 30% of intraabdominal pressure (Sapsford 1997). Ischiocaveronsus: attaches from the ischial tuberosity to the crus of the clitoris Bulbospongiosis: attaches from the perineal body, around the vagina and urethra into the body of the clitoris. Acts to close the vaginal orifice. Transversus perinei superficialis: attaches from the ischial tuberosity to the perineal body. It acts to stabilise the anterior and posterior PFM's. The superficial perineal muscles form an anterior balance for the pelvic floor. These muscles retract and elongate the urethra, voluntarily contract during micturition and closure of the vagina. Nerve supply: voluntary control of these muscles is from branches of the pudendal nerve via the sacral plexus (S2-3). Deep perineal muscles These muscles are approximately 5cm in thickness and form a strong contractile sling across the pelvic outlet. These muscles form a posterior balance for the pelvic floor. Levator ani consists of three parts-puborectalis: attaches from the pubic bone and runs as a sling along side the urethra, vagina and rectum and joins the puborectal sphincter. It acts to pull the rectum anterior aiding closure of the sphincter. -pubococcygeus: attaches from the posterior pubic bone and fascia over the obturator internus, passing along the vagina, perineal body and rectum to insert as the anococcygeal ligament on the anterior surface of the coccyx. Acts to pull the coccyx forward, elevates the pelvic organs and compresses the rectum and vagina. -iliococcygeus: attaches from the obterator internus fascia and ischial spine passing posterior- medially to join the muscle of the other side posterior to the anus. Becomes the anococcygeal ligament to the coccyx. Acts to pull the coccyx laterally and lifts the rectum. Ischiococcygeus: attaches from the ischial spine and sacrospinous ligament and inserts in the lateral margins of the coccyx and sacrum. It supports the pelvic contents and contributes to S-I joint stability. Nerve supply: branches of the pudendal nerve and sacral roots (S3-4). Uterine ligaments forming “the sling” In most cases the uterus is held in an anteverted (forward position) and anteflexed (uterine wall flexed on itself) position. These positions are held be the following ligaments: - transverse cervical ligaments which extend from the cervix laterally and attach to the ilia (if overstretched these ligaments cause an uterine prolapse) -uterosacral ligaments pass backwards from the uterus to the sacrum, encircling the rectum. These ligaments maintain the anteversion. -pubocervical ligaments pass forwards from the cervix to the pubic symphysis (NB: round ligaments arise from the uterine cornua, descend through the broad ligament and inguinal canal to attach to the labia majora. They hold the uterus in the anteverted position but do not add support to the lower segment or cervix during pregnancy). Action of the PFM in pregnancy PF function tests are reported by studies on physical movement, ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging and electromyography (EMG). "During PF contraction the anorectal junction, vagina and urethra are pulled anteriorly; all the organs are lifted forwards and in a cephalad direction and the rectum and vagina are compressed" (Sapsford 1999, pg 59). Several studies have associated the activity of the abdominal wall and pelvic floor movements. Contraction of the PFM showed visible movement of the rectus abdominis muscle (Bo et al 1990). Sapsford et al (1997) found that with maximal PFM contraction, activity occurred in the transverse abdominis and oblique muscles, with least activity in the rectus abdominis. With a posterior pelvic tilt an increase in the external oblique muscle electromyography activity was noted. Testing of the levator ani muscles with EMG, Bo et al noted that PFM activity was associated with hip and trunk movements i.e. hip adduction, pelvic tilts, gluteal contraction and sit ups (Bo et al 1994). The integrity of the pelvic floor will depend on many factors including parity, ante and postnatal exercise, intervention such as episiotomy, previous tears and maternal pelvic shape. For example with a prolonged second stage in a previous delivery the sustained active pressure of the fetal head on the pelvic floor may result in tearing of the perineal body. An episiotomy incision usually includes the vagina and perineal skin, the bulbocavernosus, superficial and deep transverse perineal muscles. In extreme cases the levator ani and external anal sphincter may be included in the incision. The episiotomy is supposed to reduce the angle and depth of the birth canal. PFM flexibility in the primigravid may need as much attention as the muscle strength of the multigravid. In the case of the first pregnancy, breathing techniques which encourage relaxation of the pelvic floor is valuable from 32 weeks on. In the multigravid breathing techniques which exaggerate a gentle PF lift on the out breath improves the function of the muscular support. The primigravid may benefit also from pelvic, lumbar and hip movements with a breathing technique which gently eases the PFM tone. The multigravid can use the same movements but exaggeration of the pelvic floor hold or lift on the out breath improves muscle tone. Placental positioning The placenta is usually formed and functioning from 12 weeks after fertilisation. It begins as a loose structure and becomes more compact as it matures, weighing more than the fetus until 20 weeks. At this time the fetal organs have matured to cope with metabolic processes. It is usual that the fetus will move to align itself along side or opposite its placenta. “Placental migration” is a contentious subject. Oppenheimer et al (2001) studied the development of the placenta using ultrasound with 26 weeks gestation to delivery. They observed the migration of the leading edge of the placenta with relationship to the cervical os at 4 weekly intervals. They found that if the placenta overlapped the cervical os by more than 20mm migration did not occur and was followed with a caesarian delivery. What influences the implantation site? Do placental villi ’migrate’ throughout pregnancy? Does the fetal movement assist in placental migration? Sutton (personal discussion October 2003) described that it is not the placenta that moves along the endometrium but rather the changing shape of the lower segment of the uterus which alters the relative position of the placenta to the cervical os from 32 weeks. Becker et al (2001) studied placental position at 20-23 weeks in 8650 cases using transabdominal ultrasonography. They concluded that an overlapping placenta to the cervical os by 20-23 weeks has the consequence of a high probability of placenta praevia at delivery. The size and length of the fetus and the position of the placenta has been examined but conclusions vary and a higher rate of placenta praevia may be considered with previous caesarian section. Collins et al (1991) undertook a prospective study to examine the relationship between placental location and nuchal cord incidence. They found that the lower the implantation of the placenta the greater the chance of the umbilical cord wrapping around the fetal neck. CAESAREAN SECTION- Tissue changes NICE guidelines (2004) on Caesarean Section (CS) reports that existing caesarean rates are between 21-33% in England & Wales. A first CS results from failure to progress (25%), presumed fetal compromise (28%), breech presentation (14%). Repeat CS is from previous CS(44%), maternal request (12%), f.t.p.(10%), fetal compromise (9%), breech (3%). A previous assisted vaginal birth (AVB) e.g. forceps, vountouse may result in a negative birth experience (1999 VBAC) and the likelihood of assistance with the next delivery. “…delivery at home reduces the likelihood of CS…and that planned childbirth in a ‘midwifery-led unit’ does not reduce the likelihood of CS.” (pg 12, NICE CS guide). A caesarean incision is made transversely 3cm above the PS, followed by a blunt incision through abdominal wall/fascias. A sharp incision through the uterine wall is followed by blunt incision to the amniotic sac. A two layered suture technique is used to repair the uterine wall (USA using one layered technique)- to reduce blood loss and reduced tissue scarring. Placenta removed by controlled cord traction. CS tissue healing takes 4-6 weeks and increases with subsequent CS. Urethral catheter is routine with regional and general anaesthetic. Urinary tract injury of 1 in 1000 CS reported but pressure incontinence or UTI within first year common. Vaginal Birth After Caesarean (VBAC) 80% of women who elect VBAC will deliver without a problem. Women who have had a previous vaginal birth will be more likely to try a VBAC. However VBAC rates are low at 33%. The risks for VBAC are dehiscence of uterine or abdo scarring (but labour can continue without problems for fetus), uterine rupture (rare- 1 in 200, but early symptoms similar to normal labour pains), fearful medical team, fearful mother. EXTERNAL CEPHALIC VERSION- IS IT SAFE? Success rates for ECV’s varies with parity, non extended breech presentation, placental position and gestation stage. Guyer and Heard (2001) audited 102 breech presentations at 37-40 weeks with 47 women who agreed to having an ECV. A 55 % success rate in turning a breech fetus without adverse reaction was noted. These researchers considered that ultrasound assessment was necessary prior to the ECV, and that ECV is an important means to reduce caesarean rates in the UK. Kirkinen and Glottal (1982) noted that by 36 weeks an anterior placental attachment increased the likelihood that an ECV did not succeed and that spontaneous version did not occur. In contrast Donald and Barton (1990) considered that a frank breech and an anteriorly located fetal spine were associated with successful versions (58% rotated) at 38-40 weeks. A breech presentation is more likely to exist if there is a placenta praevae or cervical implantation and may persist if the fetus is an extended breech and/or has a short cord. Healey et al (1997) reviewed the success of ECV with 427 women between 36-40 weeks, some having ritodrine tocolysis. They found an ECV successful in 39% of women and a reduction in breech caesarean delivery. They noted that the amniotic fluid index, placental site and fetal position significant in a successful version. Also noted was the large amount of operator time utilised and that this was an expensive procedure. Aisenbrey et al (1999) considered that subjects ECV success was dependent on low uterine tone, and this low tone was related to parity of at least one. The manual therapist can prepare the maternal tissue tone so that a well balanced and relaxed abdo-pelvic space assists the fetus in turning for itself and/or prior to an ECV (conducted by the consultant). Usually ECV’s are conducted after the 37-38 week and reattempted in a week where the fetus has returned to breech . The ECV can bruise the mother and fetus, cause amniotic fluid leakage or spontaneous delivery. The mother should be made aware of the risks prior to the ECV by the consultant. A breech presentation is more likely to exist if there is a placenta praeviae or cervical implantation and may persist if the fetus is an extended breech and/or has a short cord. Osteopathic studies for versions are limited. DeRosa and Anderle (1991) studied 32 cases with use of ritrodine tocolysis at 37 weeks and found a success rate of 59.4%. They also found that an anterior placenta and null parity significant in poorer version outcomes. Remember that a breech vaginal delivery is possible, the breech may turn cephalic in labour, the breech may me in that position for placental and cord reasons, there is a family history of breech presentation and delivery. Psychological aspects of prenatal testing Women over 35 have been shown to have more anxiety and fewer attachments to the fetus at 20 weeks than younger women (Berryman & Windridge 1995) and some health care workers accept that these women delay becoming attached to their baby until they have received positive test results. Rothman (1986) called this “tentative pregnancy”. Thomas (1998) suggests that feelings of excitement and anticipation are quickly changed when it is suggested that they might be “at risk” of having a baby with a particular problem. Hawkey (1998) says that increased fetal investigations cause women more anxiety and stress. Parents who are “at risk” have difficult decisions to face;-Moral and religious dilemmas about having tests which is some cases may cause procedure induced miscarriage or harm to the fetus and whether they will keep or terminate the baby on the strength of the results. Many of the routine tests carried out during pregnancy have very different meanings for the health care practitioner and the mother. The healthcare practitioner may know that the tests are routinely carried out to identify fetal abnormalities but the mother accepts these tests to gain reassurance that everything is normal (Farrant 1985) Health care practitioners need to be very careful with how they give information, it has been shown that under stress people are less able to remember the information offered (Ingrham & Malcarne 1995). Also peoples perception of risk varies greatly, one mother may perceive her baby is more at risk with a 1:200 chance of Down’s Syndrome that with a 5% chance, this is known as the “framing effect” (Kessler & Levine 1987). Mothers who have been in contact with or work with Down’s Syndrome or disabled children are more able to visualise what this would mean for their child and may therefore feel more at risk. We as health care practitioners also need to be aware of our role in supporting mothers in making informed decisions in their care and treatment. We need to look at our motives and prejudices to ensure that we come from a place of openness and non-judgemental support. Continually assessing our ways of practicing. We need to remember that we are in continual communication with our clients through our intention as well as through our hands and our verbal communication. We need to remember that pregnancy and childbirth is natural and not pathologise it. One of the most important ways we can support mothers is to keep pregnancy and childbirth natural and normal and to encourage them to get in touch with their inner knowing. TECHNOLOGY : In whose interest does intervention during pregnancy serve? In the UK the initial ‘booking’ session with the midwife is usually recommended before or at 12 weeks gestation so that general medical information is noted about parents & previous pregnancies, birth plan discussed, bloods, urinalysis and blood pressure are taken, monitoring the fetal heart sound and the first scan (for around 16 weeks) is booked. So what is the purpose of all of these measures and in who’s interest are they measured? Blood test findings which detect a chromosomal or genetic disorder of the fetus is fraught with controversy (particularly over the outcome of the pregnancy) and includes the possibility of false positives. What are parental choices if a positive test result for say Down’s syndrome is found? Urinalysis tests should be conducted over three consecutive weeks to ascertain a real and potential health problem such as diabetes, proteinuria. Blood pressure too requires a consecutive assessment with the same equipment in the same conditions to give an accurate reading. Bloods taken for rhesus factor are important for women with a negative blood group and a positive blood group fetus. After the first pregnancy women will be advised to take an anti-rhesus serum to reduce the risk of problems in subsequent fetal positive blood group pregnancies. Bloods that show up systemic infection such as chlamydia, syphilis, HIV & AIDs can be medically treated. Bloods that reveal low iron counts may be advised on iron supplementation (however, Odent insists that the majority of women do not have true iron deficiency or iron deficiency anaemia even when haemoglobin levels are low, but rather show the increased dilution of blood constituents from a 40-50% blood plasma volume increase). Fetal heart monitoring is an exciting first audio “listen” to the fetus for parents and gives the midwife an opportunity to ascertain a multiple pregnancy, CVS health of the fetus (HR=120-130 bpm) and the position of the placenta. Manual examination of fundal height to determine dates, number of babies, position of fetus (from 20 weeks). Engstrom et al. (1993) advise that different maternal positions changes the fundal height, i.e.fundal height is highest in the supine position while knee flexion will reduce the height. So how is the fetal heart sound heard? Once, midwives placed the stethoscope or Pinard on the maternal belly and searched for the different sounds arising from the maternal GIT system, fetal heart, placenta and umbilical cord. This equipment has been superseded by Doppler sonic aid devises (ultrasound) which magnifies the fetal heart sounds. Pat Thomas insists, in her book ‘Your Birth Rights’, that ultrasound scanning should not be routinely used as it is an under-evaluated technology in terms of safety and relevance. She concedes that high risk women such as with diabetes, pre-eclampsia that the 32-36 week scan is warranted to detect fetal growth retardation or fetal position for possible labour preparation and outcomes. Why Ultrasound: for dates, development, bonding? What is ultrasound? Proud (1997) describes that the transducer converts electrical energy into sound at high frequencies and can transfer resonance from the body into ultrasound images onto a computer screen. Fluid is represented using shades of grey or black, opaque structures (bone) are white. In first trimester- sector scanners visualise small section of anatomy, while linear scanners, used from second trimester, display a large field of view. Real-time scanners show a continuous or pulsed echo of sound. These Doppler scanners produce a very high frequency of sound and the potential for embryonic effects have been raised (McKenna 2005). Ultrasound relevance 1. A woman feels like it is a part of her medical care during pregnancy and without it she is not being properly cared for 2. A woman can visualise her baby and make a connection i.e. making the pregnancy a reality or establishing a real sense of initial bonding (Kitzinger, 2000), the first baby photo 3. The ultrasound image may reduce maternal anxiety and increase her confidence that the baby is developing well 4. Detection of some fetal malformation e.g. Down’s syndrome, cysts, fetal death 5. Detection of fetal age and gender (best after 20 weeks) 6. Necessary with other fetal testing such as amniocentesis, CVS 7. Is U/S replacing maternal instinct with hi-tech information and giving the specialist operating the machine a decision making role? Ultrasound safety 1. Ultrasound scans are not 100% accurate and women should be made aware of this fact (U/S scan can miss up to 36% of relatively obvious abnormalities-Skari et al 1998) 2. Confusing results depending on view, maternal bladder fullness, radiographer’s qualification and experience (e.g. In Ireland it is the clinical midwife sonographer who conducts, analyses and records antenatal images) 3. U/S scans use a high frequency sound waves which are directed at the fetus and placenta, the waves bounce off and the resulting echo is interpreted by the computer as an image. Therefore the strength of magnification varies according to the machine settings, machine age, the amount of maternal body fat and amniotic fluid present, length of time exposed to the waves (5 minutes maximum) 4. Pulsed Doppler is a high frequency sound wave also used for therapeutic ultrasound to produce tissue changes e.g. sports injury repair. Doppler scans use much higher frequencies than Real Time scans and fetal heart monitors 5. Repeated U/S exposure (2-5 scans during pregnancy) increases the chance of miscarriage (Saari-Kemppainen 1990) ,double the chance of premature labour (Lorenz 1990), intrauterine growth retardation (Newnham 1993),and increase the risk of stillbirth or perinatal death by 20-30% (Pastore 1999). 6. High frequency U/S scanning increases brain tissue temperature in animal experiments and may cause neural tissue development problems such as dyslexia and learning difficulties 7. The phenomena of ‘jumping babies’ when exposed to the scan waves have now been linked with possible pain or distress or hypersensitisation to the waves, particularly the ears and CNS 8. Transvaginal scan gives the fetus less protection from the waves via amniotic fluid and maternal abdominal wall, may cause break through bleeding and miscarriage. If an ultrasound does show an anomaly , the woman is usually offered further diagnostic tests to confirm the result such as a further higher resolution U/S scan, amniocentesis, chorionic villi sampling… What is your professional view of routine screening tests and the safety of diagnostic tests? Are you aware of the relevance of screening from the patient’s view and from your view? TECHNOLOGY AND ETHICS How should woman be advised on ethical decision making in first trimester pregnancy when routine screening may result in maternal and fetal/newborn complications? For example; The Scottish NHS Agency suggests that “…pregnant women in Scotland should be routinely offered two ultrasound scans to check the health of the fetus” and that this system is the most efficient method of detecting fetal abnormality. The efficiency of the system requires that women have the first scan at 10-13 weeks alongside other tests (nuchal translucency, maternal serum screening for chromosome abnormalities). The second scan at 18-22 weeks to detect developmental defects such as spina bifida, heart defects. The NHS Quality Improvement for Scotland health technology director (Dr Kohli) said “implementation of our advice will bring consistency to the service in Scotland and offer reassurance to the majority of pregnant women about their baby’s health”. The accuracy of ultrasound outcomes in early first trimester is variable (McKenna 2005). The implications of a fetal defect on a mother and her family has varied outcome such as early termination or preparation for a child requiring special attention or adoption or a normal child. Guidance from the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE 2003) recommends that healthy women (low risk women) should typically be offered 7-10 antenatal appointments rather than the common 14-18 appointments, and that the first booking be at 8 weeks. The earlier booking would help to receive and provide information on screening and planning the pregnancy, and to discover the “high risk” group of women (such as Diabetics, previous pre-eclampsia, HIV etc.) whom may require more antenatal appointments during the pregnancy. CHOICE AND CONSENT Hope (1996) outlines three components of choice: 1. Information- the quality and quantity of information available and the way it is presented 2. Education- a context in which information can be understood, the information is open for discussion and consultation and for the continuity of care 3. Power & Involvement- women need the power to exercise choice and, health professionals need to relate to women in such a way which welcomes women’s participation in decision making. Theses components also relate very closely with the legal definition (Rodgers 2002) of consent: 1. Patient Autonomy-the right of each adult of sound mind has to determine what shall be done to her body 2. Capacity to consent-the patient is able to understand the nature of treatment decisions and to make a choice based on information provided. She has the right to make a decision to refuse medical treatment even if she is aware that her decision may lead to her or her fetus’ death or injury. 3. Consent given free from duress- consent to treatment must be given freely, free from coercion. Persuasion from a health professional comes in the form of biased information and research reporting, value-judgments made on what is normal… 4. Informed consent- women must be informed of possible known risks to treatment e.g. high velocity thrust to the lower lumbar spine or pelvis may induce miscarriage before 12 weeks. “Approaching women as individuals and respecting their autonomy are fundamental aspects of (health) care. A more complex, issue is that of promoting responsibility for the outcome of choices” (Cooke 2004 pg 19). So, in manual therapy: What is the calibre of evidence-based research which supports or negates the treatment of pregnant women? Is clinical experience and case study review significant enough to represent evidence for/against antenatal treatment? e.g. In osteopathy Sandler and Korth (2004, In Midwifery best practice, Wickham) support the manual treatment of a woman during pregnancy for pain relief and preparation for childbirth. This is based upon research conducted on lower back pain during pregnancy and anecdotal evidence from a large number of case studies. Is it appropriate to use medical information as part of a “health based” model (rather than illness based model) of treatment? e.g. women attending for complementary therapies will usually be receiving advice from their doctor or midwife concerning their pregnancy. The information a woman is seeking from the complementary therapist may be different to the doctors such as drug free intervention for improved body movement/ reduction of physical pain/symptoms of pregnancy ie nausea, indigestion, optimal fetal positioning, relaxation. PRENATAL CLINICAL PRACTICE-what is best practice for pregnancy? NICE (2003) recommends four areas as guidelines for clinical practice during pregnancy ( i.e. routine prenatal care for low risk women): 1. General health screening - history of general health, previous pregnancies etc. 2. Health promotion - diet, exercise, smoking, Optimal Fetal Positioning etc. 3. Organisation of care - number of appointments, home/hospital birth etc 4. Clinical tests & screening - bloods/urine/US etc. The WHO antenatal care trial (2001) for routine care showed that a model of care with fewer antenatal visits are as effective as traditional models (average of 14 appointments) in terms of clinical outcomes and maternal satisfaction. The trial noted that screening and scans should be specific and cost effective (e.g. blood tests for rhesus negativity then followed up with anti-D to the rhesus negative mother) rather than routine. So, what does “at risk” mean? There seems to be an increased usage of this negative term, placing fear and anxiety into the hearts of pregnant women. It is associated with circumstances which may place the woman or fetus in a difficult position during the pregnancy or at childbirth e.g. a woman at low risk is one with a history of previous caesarian section, breech or face presentation OR at high risk with a history of pre-eclampsia, multiple pregnancy, fetal distress… Basically every women is seen to be at risk during pregnancy where a model of care views physiological change as illness. E.g. if a woman takes any serum screening test she will automatically have a risk category placed on her for the tested condition e.g. cystic fibrosis, Down’s. Women may also be seen at risk for not having screening tests taken. AIMS suggest that screening should be person specific, decided on by the women after she has talked through her history with her midwife, and risk be put aside to a more positive outlook of the woman’s beliefs, support and current health. REFERENCES Ainsenbrey GA, Catanzarite VA, Nelson C (1999) External Cephalic Version: predictors of success. Obstet Gynecol., Nov;94(5Pt1):783-6 Becker RH, Vonk R, Mende BC, Ragosch V, Entezami M (2001) The relevance of placental location at 20-23 gestational weeks for prediction of placenta previa at delivery: evaluation of 8650 cases. Ultrasound Obstet Gynaecol. Jun;17(6):496-501 Chamberlain G, 1991, The changing body in pregnancy, British Medical Journal, March:23302 Collins JH, Geddes D, Collins CL, De Angelis L (1991) Nuchal cord: a definition and a study associating placental location and nuchal cord incidence, J La State Med Soc, Jul;143(7):1823 Curham S, 2000, Antenatal & Postnatal Depression, Vermillion DeRosa J , Anderle LJ (1991) External cephalic version of term singleton breech presentations with tocolysis: Aretrospective study in a community hospital, Journal American Osteopathic Association, April;91(4):351-357 Donald WL, Barton JJ (1990) Ultrasonography and external cephalic version at term. AM J Obstet Gynecol. Jun;162(6):1542-5 Gardosi J, Sylvester S and Lynch C (1989) Alternative positions in the second stage of labour: a randomised controlled trial, British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 96: 12901296 Gerhardt, Sue, 2004, Why Love Matters. Routledge, London & New York Guyer MJ, Heard C (2001) A prospective audit of external cephalic version at term: are ultrasound parameters predictive of outcome? J Obstet Gynaecol. 21(6):580-582 Healey M, Porter R, Galimberti A (1997) Introducing external cephalic version at 36 weeks or more in a district general hospital a review and an audit. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. Sep:104(9):1073-9 Holford P & Lawson S, 2004, Optimum nutrition before, during and after pregnancy, Piatkus, London Kirkinen P, Ylostalo P (1982) Ultrasonic examination before external cephalic version of breech presentation. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 13(2):90-7 Lake, Frank, 1980, Studies in Constructed Confusion, Exploration of a Pre- and Peri-natal Paradigm, Bridge Pastorial Foundation. Lesley J, 2004,Birth After Caesarean (VBAC), AIMS Mancusco KM, Yancey MK, Murphy JA, Markenson GR (2000) Epidural analgesia for cephalic version: a randomised trial. Obstet Gynecol. May;95(5):648-51 Marquette GP, Boucher M, Theriault D, Rinfret D (1996) Does the use of tocolytic agent affect the success rate of external cephalic version ? Am J Obstet Gynecol., Oct;175(4 Pt1):859-61 Moore P (1997) Pregnant women get that shrinking feeling, New Scientist, 153 (2066) 5 National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2004, Caesarean section guideline number 13, NHS Odent M (2003a) Birth and Breastfeeding, 5;34-49, Clairview, East Sussex, UK Ostgaard HC, Anderson GBJ, Shultz AB, Miller JAA (1993), Influence of some biomechanical factors on low-back pain in pregnancy, Spine, Vol 18 (1) Owen N, 2002, Birth, Love and Death, Midwifery Today Raphael-Leff, 1993, Psychological Processes of Childbearing, Chapman & Hall, London Richardson CA and Jull GA (1995) Muscle control- pain control. What exercises should you prescribe? Manual Therapy 1:2-10 Roberts, H, 2003, Your Vegetarian Prgenancy, Fireside, NY Sills, Franklin, 2005, Womb of Spirit, Lecture Notes. Buddhist Psychotherapy MA. Sills, Franklin, 2006, Trans-Marginal Stress Hierarchy. Lecture Notes. Psychotherapy MA Course. Buddhist Stern D, 2005, The motherhood constellation- a unified view of parent-infant psychotherapy, Karnac, london Sutton J (2001) Let birth be born again, Birth Concepts, Sarsen Press, London Sweet BR (Ed), (1988) Mayes’ Midwifery, 11th Edition, Bailliere Tindall, London Terry K, 2005, The sperm journey/The egg journey, Editorial Colibri, Mexico. Verney T & Weintraub P, 2002, Preparenting- Nurturing your child from conception to birth, Simon & Schuster, New York Verney T, 2002, The secret life of the unborn child, Time Warner Books, London Wegela K, 1996, How to Be a Help Instead of a Nuisance, Shambhala, Boston & London Wirth F, 2001, Prenatal parenting, Collins, NY Web pages www.modent.com www.birthworks.com www.birthconcepts.com www.sheilakitzinger.co.uk www.nice.org.uk www.aims.org.uk