NRCO-12-197V1 * Submission

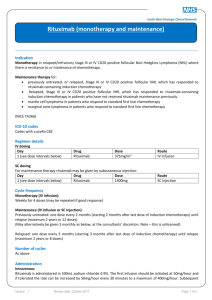

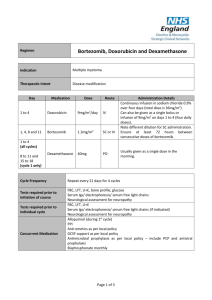

advertisement

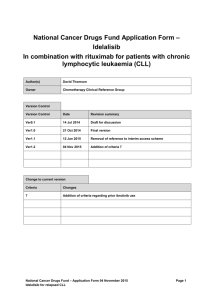

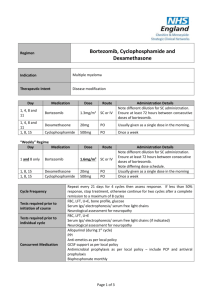

Drug rechallenge and treatment beyond progression— implications for drug resistance Supplementary Text Elizabeth A. Kuczynski, Daniel J. Sargent, Axel Grothey and Robert S. Kerbel Additional rechallenge agents Bortezomib Bortezomib (Valcade) is a first-in-class proteasome inhibitor active in multiple myeloma and is used alone or with chemotherapy and immunomodulating agents such as thalidomide. Retrospective studies suggest that retreatment with bortezomib is effective in patients who progressed after stopping bortezomib.1–3 In initially bortezomib-responsive but heavily pretreated patients, re-treatment with bortezomib yielded a similar TTP to initial treatment1,2 and an ORR >60% at rechallenge.1–3 Initial response was also found to be predictive of secondary response to bortezomib in a few studies.1,2 A follow-up of the VISTA (Valcade as Initial Standard Therapy in Multiple Myeloma) phase III clinical trial compared second line therapies following initial melphalan and prednisone with or without bortezomib.4 Response rates of 178 patients in the bortezomib arm were similar (47% versus 41% versus 59% for bortezomib, thalidomide and lenalidomide based therapies, respectively). Responses to bortezomib were relatively similar when bortezomib was (ORR 47%) or was not used as first line therapy (ORR 59%). Two prospective trials on bortezomib rechallenge have been reported. A single-arm communitybased phase IV trial of 32 heavily pre-treated patients found that although retreatment resulted in decreased TTP, the ORR was favourable (50%).5 A phase II international open-label trial ‘RETRIEVE’ involved 130 patients that were retreated with bortezomib after ≥6 months TFI.6 An ORR of 40% (plus 18% minimal response) was reported at retreatment, and a higher proportion of patients who initially achieved a CR (63% of patients) versus a PR (52%) achieved greater than a PR at rechallenge. Generally, bortezomib retreatment is well tolerated with no new or cumulative (and occasionally fewer2,4) toxicities.1,3,6 Both retrospective and prospective data suggest that in those patients with a TFI ≥6 or 12 months, the ORR is significantly higher.1,2,4,5 The efficacy of bortezomib retreatment suggests that relapsed patients are not intrinsically more resistant, and that there is a lack of selection for truly resistant clones. The NCCN clinical practice guidelines currently state that patients who relapse >6 months following induction of bortezomib may be retreated with the same regimen if they have not received intervening therapies. Alemtuzumab Alemtuzumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody targeting the CD52 cell surface glycoprotein, is approved as single agent for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). It is given until maximal response or for a minimum of 12 weeks,7 but options at relapse are unclear.8 A handful of case reports and case series have documented heavily pre-treated CLL patients re-achieving a PR after relapse following a second course of alemtuzumab.9–13 Only one large retrospective analysis has been published regarding alemtuzumab rechallenge.8 30 heavily pre-treated B-cell CLL patients were identified who relapsed and were immediately rechallenged with alemtuzumab. Of 29 evaluable patients, 14 achieved a PR and 6, SD. Importantly, 85% of those who responded to initial alemtuzumab responded to rechallenge, and PFS at each exposure was not significantly different. A third course of alemtuzumab was also active. Preliminary results in 26 patients by the same authors found that patients treated within 10.3 months after the last dose of alemtuzumab had a significantly shorter median OS than if retreatment was later. 14 Current guidelines allow alemtuzumab retreatment but this strategy has yet to be tested in prospective studies.7 Rituximab Rituximab, a chimeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, is used to treat B-cell lymphomas. Due to high efficacy, rituximab is routinely re-administered over a 4 week course ( ± chemotherapy) in first and sequential lines of therapy based on early phase II studies.15,16 In one trial, 57 initially 1 responding non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients were re-treated with rituximab after PD (monotherapy in 61% initially and 49% subsequently).17 Estimates of time to progression (TTP) at retreatment (17.8 months) were longer but not significantly different from initial TTP (12.4 months; P = 0.224). In the second, 13 progressed patients were re-administered rituximab leading to disease control in 84% and a second PFS of 5.1 months (versus 8.2 months at initial treatment).18 Some patients also responded to greater than three courses of rituximab.17,18 In other patient populations, retreatment with rituximab-based therapy following relapse or refractoriness yields similar PFS and response rates to initial treatment.15,19 Monotherapy rechallenges are reported in only a fraction of patients.20,21 Of 178 patients reintroducted to a similar therapy, only 12 received monotherapy and, of these 3 patients achieved a CR and 7 patients a PR.15 A similar study observed that out of those retreated with rituximab monotherapy (11 patients), 4 patients experienced a CR, 2 patients PR and 4 patients SD.19 ‘Treat as needed’ rituximab has been compared head-to-head with rituximab maintenance therapy. A phase II trial randomly assigned 90 indolent non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients on induction rituximab to receive either re-introduction after relapse or maintenance rituximab.22 In the maintenance group, PFS and final overall and complete response rates were superior. However, the total duration of rituximab benefit was similar across the groups (maintenance 31.3 months versus 27.4 months), in addition to 3 year survival. The randomized phase III RESORT trial found a similar time to treatment failure in the maintenance (one infusion every 12 weeks) versus retreatment arms (3.9 and 3.6 years; not significant), suggesting that retreatment improves benefit after an initial course of therapy. There was no difference in health-related quality of life or anxiety between groups. Although maintenance groups received more doses of rituximab,22,23 and retreatment required the development of progressive disease, outcomes of the two dosing strategies were similar. Trabectedin Trabectedin is a DNA-damaging compound indicated for the treatment of soft tissue sarcomas. Rechallenge after relapse has been reported in cohorts of 8 and 12 patients, with all patients experiencing tumour control at re-exposure following a chemotherapy-free interval.24,25 A Phase II trial (NCT01303094) currently recruiting participants will randomize sarcoma patients to continuous or trabectedin with a drug holiday after 6 cycles of stable disease.26 Gemcitabine* A multi-centre retrospective study on pancreatic adenocarcinoma patients compared survival outcomes in 183 patients after first line gemcitabine-containing therapy. Of patients with initial PFS ≥6 months, 6 patients that were rechallenged with single agent gemcitabine had significant survival improvements compared to 16 treated with another drug.27 Additionally, there is a single case report of gemcitabine rechallenge in clear cell ovarian carcinoma.28 Everolimus* Inhibitors of mTOR are used sequentially with TKIs to stabilize RCC growth. To date, one case report documented successful mTOR inhibitor rechallenge in an RCC patient.29 This patient progressed on the mTOR inhibitor everolimus as well as two different anti-angiogenic TKIs. Since everolimus achieved the best response (a PR; PFS 33 months), he was retreated with this agent and once again achieved a PR lasting >5 months, with little toxicity. Crizotinib* The ALK inhibitor crizotinib is effective in ALK positive cases of NSCLC. A recent case report of one NSCLC experienced 18 months of total disease control due to this agent.30 After progressing on critozinib therapy (initial PFS 8 months), she received 16 months of intervening pemetrexed then experienced initial tumour shrinkage following crizotinib rechallenge. Pemetrexed‡ The anti-folate pemetrexed plus platinum has recently been established as first line treatment for malignant pleural mesothelioma. This tumour is highly aggressive and second line agents are currently undefined. Case reports and series and small retrospective studies have observed favourable responses particularly in those with a prolonged intervening period31,32 or first line PFS >12 months.33 Disease control rates reported range from 43–65% at retreatment.33–35 ‘True’ rechallenges have not been clearly reported since the platinum agent may vary (of be removed) 2 at rechallenge.32–35 The largest study to date, a multicentre survey of 423 malignant mesothelioma patients, revealed that retreatment with platinum-based chemotherapy produced improved responses when initial TTP ≥12 months, and compared to pemetrexed-naive patients, retreatment improved both disease control rate and PFS.36 2009 guidelines for mesothelioma treatment recommend retreatment in patients with a good initial response to first line chemotherapy until other second line agents are established.37 Diethylstilbestrol§ Prostate cancer is initially dependent on intrinsic androgens for sustained growth necessitating surgical or chemical castration consisting of anti-androgens and GnRH analogues. At progression patients are termed castration resistant and further endocrine therapy (diethylstilbestrol or corticosteroids which further manipulate the androgen pathway) and subsequently salvage chemotherapy is initiated. Surprisingly, such patients have been observed to regain sensitivity to hormonal therapy following (or not) chemotherapy, indicating that drugs targeting the androgen pathway are still active.38–41 Sundar and Cox have observed that the same phenomenon applies when exposure to diethylstilbestrol is repeated.42,43 For instance, in a subset of androgen refractory patients who had received prior docetaxel and progressed on prior diethylstilbestrol, 6 of 7 patients responded to rechallenge with diethylstilbestrol.42 In a phase II trial, castrate patients who had failed diethylstilbestrol and dexamethasone, stopped hormone therapy and then received chemotherapy, were retreated with this diethylstilbestrol and dexamethasone post-progression.44 43% of 28 patients responded to rechallenge (both castrate and non-castrate patients after chemotherapy), including 8 initial non-responders. Obtaining a PSA response at rechallenge was associated with an increase in OS (16.5 versus 5.5 months). The same phenomenon has been observed in a case report of patients on the GnRH agonist goserelin.45 Together, this work has challenged the notion of ‘castration resistance’ and treatment options, and raises the question of whether rechallenge with an anti-androgen will be similarly effective after a hormone-free interval. Notes *Studies not listed in Supplementary Tables. ‡ With the exception of a few case studies, studies regarding pemetrexed rechallenge rarely involve using the same drug combination at each exposure. Data not in Supplementary Tables. § This data is provided for interest, as diethylstilbestrol represents an older example of rechallenge. Data not in Supplementary Tables. 1. Hrusovsky, I. et al. Bortezomib retreatment in relapsed multiple myeloma - results from a retrospective multicentre survey in Germany and Switzerland. Oncology 79, 247–254 (2010). 2. Taverna, C., Voegeli, J., Trojan, A., Olie, R. A. & von Rohr, A. Effective response with bortezomib retreatment in relapsed multiple myeloma--a multicentre retrospective survey in Switzerland. Swiss Med. Wkly. 142, w13562 (2012). 3. Ciolli, S., Leoni, F., Casini, C. & Bosi, A. Feasibility and efficacy of bortezomib re-treatment in multiple myeloma. Haematologica 92, 260a (2007). 4. Mateos, M. V. et al. Bortezomib plus melphalan and prednisone compared with melphalan and prednisone in previously untreated multiple myeloma: updated follow-up and impact of subsequent therapy in the phase III VISTA trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 28, 2259–2266 (2010). 5. Sood, R. et al. Retreatment with bortezomib alone or in combination for patients with multiple myeloma following an initial response to bortezomib. Am. J. Hematol. 84, 657–660 (2009). 6. Petrucci, M. T. et al. A prospective, international phase 2 study of bortezomib retreatment in patients with relapsed multiple myeloma. Br. J. Haematol. 160, 649–659 (2013). 7. Osterborg, A. et al. Management guidelines for the use of alemtuzumab in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia 23, 1980–1988 (2009). 8. Fiegl, M. et al. Successful alemtuzumab retreatment in progressive B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a multicenter survey in 30 patients. Ann. Hematol. 90, 1083–1091 (2011). 9. Rieger, K., Von Grünhagen, U., Fietz, T., Thiel, E. & Knauf, W. Efficacy and Tolerability of Alemtuzumab (CAMPATH-1H) in the Salvage Treatment of B-Cell Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia—Change of Regimen Needed? Leuk. Lymphoma 45, 345–349 (2004). 10. Pangalis, G. A., Dimopoulou, M. N., Angelopoulou, M. K., Tsekouras, C. H. & Siakantaris, M. P. Campath-1H in B-chronic lymphocytic leukemia: report on a patient treated thrice in a 3 year period. Med. Oncol. 17, 70–73 (2000). 11. Rai, K. R. et al. Alemtuzumab in previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients who also had received fludarabine. J. Clin. Oncol. 20, 3891–3897 (2002). 12. Egyed, M. et al. Fifth successfully retreatment with alemtuzumab in patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. 3 Blood 110, (2007). 13. Thieblemont, C. e. a. Feasibility of Alemtuzumab re-treatment in heavily pretreated refractory B-CLL/SLL [abstract]. Blood 102, (a5165) (2003). 14. Fiegl, M. et al. Retreatment with alemtuzumab after a first, successful alemtuzumab treatment in B-CLL [abstract]. Blood 110, (a4714) (2007). 15. Johnston, A. et al. Retreatment with rituximab in 178 patients with relapsed and refractory B-cell lymphomas: a single institution case control study. Leuk. Lymphoma 51, 399–405 (2010). 16. Abdulla, N. E., Ninan, M. J. & Markowitz, A. B. Rituximab: current status as therapy for malignant and benign hematologic disorders. BioDrugs 26, 71–82 (2012). 17. Davis, T. A. et al. Rituximab anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: safety and efficacy of re-treatment. J. Clin. Oncol. 18, 3135–3143 (2000). 18. Igarashi, T. et al. Re-treatment of relapsed indolent B-cell lymphoma with rituximab. Int. J. Hematol. 73, 213– 221 (2001). 19. Lemieux, B. et al. Second treatment with rituximab in B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: efficacy and toxicity on 41 patients treated at CHU-Lyon Sud. Hematol. J. 5, 467–471 (2004). 20. Tobinai, K. et al. Rituximab monotherapy with eight weekly infusions for relapsed or refractory patients with indolent B cell non‐Hodgkin lymphoma mostly pretreated with rituximab: A multicenter phase II study. Cancer Sci. 102, 1698–1705 (2011). 21. Coiffier, B. et al. Bortezomib plus rituximab versus rituximab alone in patients with relapsed, rituximab-naive or rituximab-sensitive, follicular lymphoma: a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 12, 773–784 (2011). 22. Hainsworth, J. D. et al. Maximizing therapeutic benefit of rituximab: maintenance therapy versus re-treatment at progression in patients with indolent non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma--a randomized phase II trial of the Minnie Pearl Cancer Research Network. J. Clin. Oncol. 23, 1088–1095 (2005). 23. Kahl, B. et al. Results of Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Protocol E4402 (RESORT): A randomized phase III study comparing two different rituximab dosing strategies for low tumor burden follicular lymphoma [abstract LBA-6]. Presented at the 53rd ASH Annual Meeting and Exposition, 13 December 2011. 24. Sanfilippo, R. et al. Rechallenge with trabectedin in patients with responding myxoid liposarcoma [abstract]. J. Clin. Oncol. 27, 10575 (2009). 25. Sanfilippo, R. et al. Surgery of residual disease of myxoid liposarcoma (MLS) patients responding to trabectedin [abstract]. J. Clin. Oncol. 28, 10056 (2010). 26. US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov [online], http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01303094?term=NCT01303094&rank=1. (2013). 27. Reni, M. et al. A multi-centre retrospective review of second-line therapy in advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 62, 673–678 (2008). 28. Ferrandina, G. et al. A case of drug resistant clear cell ovarian cancer showing responsiveness to gemcitabine at first administration and at re-challenge. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 60, 459–461 (2007). 29. Roca, S. et al. Efficacy of re-challenging metastatic renal cell carcinoma with mTOR inhibitors. Acta Oncol. 50, 1135–1136 (2011). 30. Browning, E. T., Weickhardt, A. J. & Camidge, D. R. Response to crizotinib rechallenge after initial progression and intervening chemotherapy in ALK lung cancer. J. Thor. Oncol. 8, e21 (2013). 31. Hayashi, H. et al. Retreatment of recurrent malignant pleural mesothelioma with cisplatin and pemetrexed. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 15, 497–499 (2010). 32. Razak, A. R. A., Chatten, K. J. & Hughes, A. N. Retreatment with pemetrexed-based chemotherapy in malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM): A second line treatment option. Lung Cancer 60, 294–297 (2008). 33. Ceresoli, G. L. et al. Retreatment with pemetrexed-based chemotherapy in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma. Lung Cancer 72, 73–77 (2011). 34. Steer, J., Bough, G., Razak, A. R. A., Meachery, G. J. & Hughes, A. Life after first-line chemotherapy in malignant pleural mesothelioma: a North-East England experience. Clin. Oncol. 22, 231–235 (2010). 35. Serke, M. & Bauer, T. Pemetrexed in second-line therapy in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma. J. Clin. Oncol. 25, 18198 (2007). 36. Zucali, P. A. et al. Second-line chemotherapy in malignant pleural mesothelioma: Results of a retrospective multicenter survey. Lung Cancer 75, 360–367 (2012). 37. Scherpereel, A. et al. Guidelines of the European Respiratory Society and the European Society of Thoracic Surgeons for the management of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Eur. Respir. J. 35, 479–495 (2010). 38. Attard, G. et al. Phase I clinical trial of a selective inhibitor of CYP17, abiraterone acetate, confirms that castration-resistant prostate cancer commonly remains hormone driven. J. Clin. Oncol. 26, 4563–4571 (2008). 39. Grenader, T. & Goldberg, A. Reinduction of hormone sensitivity to goserelin following chemotherapy with vinorelbine in castration-resistant prostate cancer. ScientificWorldJournal 10, 1814–1817 (2010). 40. Shamash, J. et al. Chlorambucil and lomustine (CL56) in absolute hormone refractory prostate cancer: reinduction of endocrine sensitivity an unexpected finding. Br. J. Cancer 92, 36–40 (2005). 41. Serrate, C. et al. Diethylstilbestrol (DES) retains activity and is a reasonable option in patients previously treated with docetaxel for castration-resistant prostate cancer. Ann. Oncol. 20, 965 (2009). 42. Sundar, S. & Cox, R. Re-induction of sensitivity to diethylstilbestrol in docetaxel-treated androgen refractory prostate cancer [abstract]. 2008 Genitourinary Cancers Symposium, 172 (2008). 43. Cox, R. A. & Sundar, S. Re-induction of hormone sensitivity to diethylstilboestrol in androgen refractory 4 prostate cancer patients following chemotherapy. Br. J. Cancer 98, 238–239 (2008). 44. Shamash, J. et al. A phase II study investigating the re-induction of endocrine sensitivity following chemotherapy in androgen-independent prostate cancer. Br. J. Cancer 98, 22–24 (2008). 45. Smith, D. & Plowman, P. N. Recovery of hormone sensitivity after salvage brachytherapy for hormone refractory localized prostate cancer. Int. Braz. J. Urol. 36, 283–291 (2010). 5