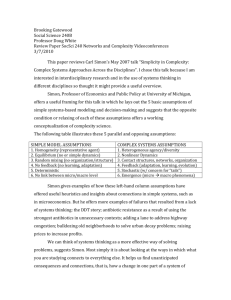

Theoretical foundation of Educational Administration and Policy

advertisement

PEDU 7206 Foundations of Educational Administration and Policy Lecture 1 Introduction: In Search of a Common Ground for the Theory & Practice of Educational Administration and Policy A. Where Do We Stand? In Search of a Common Ground for Educational Policy and Administration Studies 1. There are in general two ways to locate the common ground for educational administration and educational policy. One is to follow the distinction made by Herbert A. Simon between Policy and administration. The other is the distinction made most notably by Douglass C. North between institution and organization. 2. Herbert C. Simon’s formulation: a. Herbert A. Simon, the Nobel laureate in Economics in 1978, in his now classical work in public administration Administrative Behavior: A Study of Decision-Making Processes in Administrative Organization (1997/1945), has formulated the following distinction and connection between the term administration and policy. b. Simon underlines that it is common in political science and public administration to made the distinction between ‘policy questions’ and ‘administrative question’ and to identify “’policy with ‘deciding’ and ‘administration’ with doing.” (Simon, 1997, P. 63) He has quoted Goodnow’s words to substantiate his point. “Politics has to do with policy or expression of the state will. Administration has to do with the execution of these policies.” (Goodnow, quoted in Simon, 1997, P. 63) Such a distinction has further been differentiated into the work of the legislators, who are supposed to make the policy-decisions and even laws, and the administrators, who are to implement the policies and enforce the laws. (P. 65-67) c. However, Simon refutes such a distinction and stipulates that policy (i.e. deciding) and administration (doing) are both integral parts in the public-administrative process. In the opening page of his book, he underlines that i. “Administration is ordinarily discussed as the art of ‘getting things done.’ Emphasis is placed upon processes and methods for insuring incisive action. Principles are set forth for securing concerted action from groups of men. In all this discussion, however, not very much attention is paid to the choice which prefaces all action― to the determining of what is to be done rather than to the actual doing.” (Simon, 1997, p.1) ii. “Although any practical activity involves both ‘deciding’ and ‘doing’ it has not commonly been recognized that a theory of administration should concerned with the processes of decision as well as with the process of action. …The task of ‘deciding’ pervades the entire administrative organization quite as much as does the task of ‘doing’ ― indeed, it is integrally tied up with the latter. A general theory of administration must include principles of organization that will insure correct decision-making, just as it must include principles that will insure effective action.” (Simon, 1997, p.1) 1 1 Pang & Tsang Foundations of EAP d. Simon has further traced the “vague” distinction between policy and administration back to another dubious distinction in administrative science, that is, between fact and value, or more specifically between factual and ethical propositions in administrative science. i. Simon underlines that the decision-making processes in administrative organizations inevitably involve both factual and ethical propositions, in other words, concern both issue of truth and that of good. In Simon’s own words, “Decisions are something more than factual propositions. To be sure, they are descriptive of a future state of affairs, and this descriptive can be true or false in a empirical sense, but they possess, in addition, an imperative quality―they select one future state of affairs in preference to another and direct behavior towards the chosen alternative. In short, they have an ethical as well as a factual content.” (Simon, 1997, P. 56) ii. Accordingly, in evaluation of the correctness of a decision made by an administrative organization, two criteria must be taken into account, namely the ethical and factual elements of the decision. “’Correctness’ as applied to imperatives has meaning only in terms of subjective human values. ‘Correctness’ as applied to factual propositions means objective, empirical truth.” (Simon, 1997, P. 62) c. In conclusion, Simon stipulates that the nature of administrative science is made up of two parts, as theoretical and practical sciences. (Simon, 1997, P. 356-360) i. “Science may be of two kinds: theoretical and practical. Thus, scientific propositions may be considered practical if they are state in some such form as: ‘In order to produce such and such a state of affairs, such and such must be done.’ But for any such sentence, an exactly equivalent theoretical proposition with the same conditions of verification can be stated in a purely descriptive form: ‘Such and such a state of affairs is invariably accomplished by such and such conditions.’ Since the two propositions have the same factual meaning, their difference must lie in the ethical realm. More precisely the difference lies in the fact that the first sentence possesses an imperative quality which the second lack.” (Simon, 1997, P. 356) ii. “Using the term ‘theoretical’ and ‘practical’,….an administrative science may take either of these two modes.” (Simon, 1997, P. 160) d. Accordingly, think about the studies of educational administration and policy and see which scientific modes should they be located. 2. Douglas C. North’s distinction between institution and organization: a. Douglas C. North, the Nobel laureate in Economics in 1993, in his book Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance indicates at the outset that i. “A crucial distinction in this study is made between institutions and organization. Like institutions, organizations provide a structure to human interaction. …Conceptually, what must be clearly differentiated are the rules from the players.” (North, 1990, P. 4) ii. North defines that “institutions are the rule of the game in a society or, more formally, are the humanly devised constraints that shape human interaction. In consequence they structure incentives in human exchange, whether political, social, or economic. …Institutions reduce uncertainty by providing structure to everyday life.” (North, 1990, P. 3) iii. While he defines organization as “groups of individuals bound by some common purpose to achieve objectives. Modeling organizations is analyzing governance 2 2 Pang & Tsang Foundations of EAP structure, skills, and how learning by doing will determine the organization’s success over time.” (North, 1990, P. 5) iv. Accordingly, institution and organization can be construed as interactively and interdependently related. “What organizations come into existence and how they evolve are fundamentally influenced by the institutional framework. In turn they influence how the institution framework evolves.” (North, 1990, P. 5) b. Applying this conceptual distinction to economic analysis, organizations are practically the firms, which can deploy their internal resources in whatever way in achieving their objectives; while the institution is the market and its rules, which will set the limits as well as possibilities for the firms to operate. c. As for the field of education, the organizations are schools, which can organize their teaching and learning resources in a way to attain the educational missions that they have identified. But all schools, no matter public and private, must comply to the rules, regulations and policies laid down by the educational institution and authority. B. On What Footings do we Stand? In Search of the Theoretical and Practical Foundations of EAP Studies 1. Administration and Policy in Education are social actions seeking theoretical and practical reasons a. Weber's aporia for social researchers "Sociology is a science concerning itself with interpretive understanding of social action in order thereby to arrive at a causal explanation of its course and consequence. We shall speak of 'action' insofar as the acting individual attaches a subjective meaning to his behavior. …Action is 'social' insofar as its subjective meaning takes account of the behavior of others and is thereby oriented in its course." (Weber, 1977, p. 38) i. Problem of positive sociology: Weber at the same time stipulates that sociology should strive to render objective “causal explanation” of course and consequences of social action. ii. Problem of interpretive sociology: Weber stipulates that sociology should endeavor to provide "interpretive understanding" of the "subjective meaning" underlying social actions. iii. Problem of the possibility of social reciprocity: Weber finally stipulates that sociology should account for how subjective-meaning endowing individuals come to consensus and act cooperatively in social actions or even in regular social relationships. b. John Rawls’ aporia for political liberals In his book Political Liberalism, John Rawls asserts that political liberalism is to address the question: “How is it possible for there to exist over time a just and stable society of free and equal citizens who still remain profoundly divided by reasonable religious, philosophical, and moral doctrines?” (1993, P. 47) i. Distinction between the rational and the reasonable ii. The predicaments of reasonable disagreement in political liberalism iii. In search of practical grounds for the settlement of reasonable disagreement in modern societies, including their educational institutions and school organizations. 3 3 Pang & Tsang Foundations of EAP 2. Identifying the theoretical foundations of EAP studies a. The methodological foundations of EAP enquiries b. The epistemological foundations of EAP enquiries c. The ontological foundations of EAP enquiries 3. Identifying the practical foundations of EAP studies a. The rationality bases of EAP practices b. The power bases of EAP practices c. The reason and reasonableness bases of EAP practices d. The organizational and institutional contexts of EAP practices e. The system and lifeworld contexts of EAP practices 4 4 Pang & Tsang Foundations of EAP