Big Ideas and Craftmaking: A Case for Use in Middle School Ceramics

advertisement

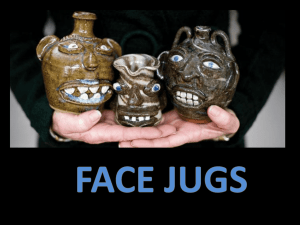

Big Ideas and Craftmaking: A Case for Use in Middle School Ceramics Elaina M. Fejes Upon initial examination, one may carry the assumption that big ideas do not apply to craft making since emphasis on technical skill and craft seem to go hand in hand (Anderson & McRorie, 1997; Sessions 1999), whereas meaning making puts into context art and the world of the artist. For decades, the approach to teaching ceramics has been through technique and media exploration, and rarely has incorporated overarching theme or meaning making behind the work. How then can the principles as defined by Walker (2003) be applied to the teaching of ceramics, that is, teaching meaning through art making using big ideas? This paper addresses how art educators can apply the approach of big ideas to a middle school ceramics curriculum. Several approaches utilize the umbrella of big ideas such as cultural heritage, community, collaboration, and service, which will be detailed in this document. In order for art teachers to engage students in meaning making, teachers must recognize and understand its complexity. Big ideas, as articulated by Walker (2003), requires the melding of the process of art making with meaning making that stems from a broader artistic and personal knowledge base. Walker (2003) cited the use of modern and contemporary artists as a way to connect to students to their lives outside the classroom. She suggested teachers determine boundaries for students such as media and subject matter in order for students to be successful and to make effective choices in their art making. According to her thematic approach, technical skill acquisition falls second to expressing and exploring meaning through artwork. She suggested themes of identity, power, and nature and to examine exemplary artists whose works incorporate those themes. Teachers may refer to modern and contemporary artists who exemplify art making as a meaning making endeavor according to Walker’s (2003) approach; therefore, students will understand the use of technique as a means to express an overarching idea. Media exploration will achieve a broader goal in that students will use those media techniques to solve art problems on their own, not from rote formulas. Artists suggested by Walker (2003) (i.e. Chuck Close, Deborah Butterfield, Andy Goldsworthy, and Sandy Skoglund) work with various media including: sculpture, environmental art, painting, collage, assemblage, and other mixed media works. Walker (2003) thoroughly covered big ideas in fine art, but Big Ideas and Craftmaking: A Case for Use in Middle School Ceramics Elaina M. Fejes ignoreed this approach when applied to craft. Clay has the potential to be an excellent medium for meaning making due to its prevalence in cultural history as well as being an important means of expression still today (Sessions, 1999). The importance of craft should not be reduced for it has excellent meaning making potential in the art classroom. Unfortunately ceramics in the classroom is often underused, misused, trivialized and pushed to a school’s periphery (Brewer, 1991; Sessions, 1999). The construction of big ideas for the classroom is in essence forming a contextualist curriculum. “…[C]ontextualist curriculum de-emphasizes manual and technical skills in favor of those skills connected to constructing and interpreting meaning (signs, symbols, and codes within a mutually understandable social matrix).” (Anderson & McRorie, 1997, p.12). A formalist curriculum in contrast solely focuses on the aesthetic “art for art’s sake” view of art objects that has predominately been associated with traditional ceramics curriculum. There is no reason ceramics could not be approached from a contextual point of view rather than a formalist point of view as it is most commonly approached. Using big ideas outlined below can assist art educators in practicing contextualist curriculum theory. Throughout history, clay has been used by many different cultures (Simpson et al., 1998). A very primal human connection with clay is deeply rooted in human history. Roy Strassberg is an exemplar in the world of ceramic sculpture and is known for connecting ceramics to the big idea of cultural history. His work responds to the Holocaust in a series of sculptures he calls Bone Structures. Each sculptural piece communicates many strong emotions, such as sorrow. His work poses many questions, such as, can the devastation of the Holocaust be mended and healed (Brown, 2007)? He does not attempt to answer those questions directly in his work, for it is up to the viewer to contemplate. Brown (2007) presented an exercise in meaningful art making using a thematic approach, cultural history. The assignment aims for students to find a deep connection to their own cultural history. Required is a demonstration of Strassberg’s ceramic technique as well as a group discussion about the ideas behind his work. Students are then asked to create a ceramic work that represents a significant historical event. The assignment offered collaboration, individual interpretation, connection to student Big Ideas and Craftmaking: A Case for Use in Middle School Ceramics Elaina M. Fejes life outside school, open-ended results, and potential for meaning making in ceramics appropriate for secondary level students. Brown’s exercise demonstrated that educators should think of ceramics as another important medium to create and express meaning, rather than thinking of ceramics as “craftmaking”. One big idea that applies particularly well to teaching ceramics is community, which can provide numerous possibilities to a middle school art curriculum. To begin, teachers must strive to constantly connect art to life in order to help students make sense of their world (Anderson & McRorie, 1997; Hagaman, 1990; Sessions, 1999; Stephens, 2006). Furthermore, community is “an actual and natural curriculum theme” (Simpson, et al., 1998, p.296). The authors went on to describe a middle school teacher’s unit involving ceramics and the theme of community. A prevalent sense of “placelessness” among his diverse students and awareness that they knew little about the built environment that surrounded them led a middle school art teacher to design a unit that addressed both of these issues… Eighth graders did façade drawings that were later translated into slab vessels or reliefs in clay… Various elements were understood through this learning experience: the links among architecture, landscaping, and geographic constraints that establish the image of a community; the stories that buildings told in the students’ and other artists’ work; and the contribution that visual details like moldings and door handles make toward creating meaning. (Simpson, et al., 1998, pp.296-297) Students in middle school begin to build awareness of their community at this time in their lives (Simpson, et al., 1998). They have the ability to identify not only the problems around them, but can provide innovative solutions to those problems. Art teachers can facilitate this discovery through meaningful problem sets in art once students identify their community concerns. The display of artwork in public spaces has many positive real world benefits for students and is mutually beneficial to the community (Stephens, 2006). Sessions (1999) described the subway tile work of Joyce Kozloff. In her Big Ideas and Craftmaking: A Case for Use in Middle School Ceramics Elaina M. Fejes tile murals, she focused on community artifacts and artistic assimilations of qualities of place and community. Finding public artwork such as Kozloff’s pushes these community and personal agendas that may be incorporated in the classroom. The possibilities for meaning making abound when one utilizes community and community-based learning as a curricular approach to ceramics, especially at the middle school level. When considering working with clay as a way of creating meaning, the art educator may take a child-centered approach (Brewer & Colbert, 1992; Brown, 2007; Hagaman, 1990; Simpson, et al., 1998). Child-centeredness begins with a collaborative classroom. Collaboration, as a big idea in the classroom requires teachers and students to revise their roles. Teachers must allow students to become active contributors to the classroom culture and decision-making. When students face greater responsibility, they will feel greater ownership of the work they produce (Stephens, 2006). Teachers should allow the class to aid in the selection of the big idea, theme, and sub-themes (Simpson, et al, 1998). The task becomes less daunting when the teacher considers his or her population and allows for class involvement and input. Collaborative learning carries real life applications. Students learn from one another. Skills will not be mastered without others according to Bruner (as cited in Hagaman, 1990) who stated that the world is [added for emphasis] others. The role of peer interaction becomes especially critical when students reach middle school. One way to insure “community values” is to choose “[c]ollaboratively derived themes, functions of art to investigate together, and agreed-upon media and techniques that provide for collaborative as well as individual exploration…” (Anderson & McRorie, 1997 p. 14). Connection to cultural history and collaboration are important learning experiences, but as Taylor (2001) stated, “[a]ctive participation is needed to connect art and life” (p. 42). Connecting art to life has the potential to serve a deep need of the community, a need recognized by the creators of The Empty Bowls Project. The project began in Michigan in 1990 as an attempt to raise money for a food drive. The fundraiser evolved into a class project to make ceramic bowls for a fundraising meal. Attendees were served soup in the ceramic bowl for the price of a ticket. Guests were allowed to keep the bowl as a Big Ideas and Craftmaking: A Case for Use in Middle School Ceramics Elaina M. Fejes reminder to continue to support the fight against hunger. Based on the success of this fundraiser, the originators developed The Empty Bowls Project as it is known today. Facilitating an Empty Bowls fundraiser has real life applications as well as giving civil and social responsibilities to students (Taylor, 2001). If given these responsibilities early on, students have the potential to build a lifelong duty to serving their community, especially through art. The intent to help the community is a completely unique motivator for participants to create the bowls. Technical execution of ceramic pots becomes secondary to the love and care that goes into making the ceramic mementos that will be used by someone in the community. Most importantly, art and service learning become mutually beneficial to all those involved, providing satisfaction for volunteers and meeting a need in the community. Arguments can be made against contextualist and thematic approaches to teaching craft. Lowenfeld and Brittain (as cited in Brewer, 1991) attested to a different child-centered approach. They emphasized the mode of expression and not the content. Teachers are to ask specific questions to activate passive knowledge in students. They argued that individual expression may be quelled if students are exposed to past and current trends in art. Sessions (1999) and Walker (2003) recommended using cultural and artistic exemplars to enlighten and inspire, while Lowenfeld and Brittain stressed that the creation of art comes about by increased individual and environmental awareness. A study was conducted to challenge these notions using 3 different instructional strategies with seventh-grade students and their creation of ceramic vessels. Three groups of about 25 seventh-graders were asked to create a ceramic vessel, but were taught using three very different curricular approaches. Group one was the studio/technical group, group two was the historical/cultural group, and group three was the questioning/discussion group. Group one observed demonstrations and were taught terminology of ceramic techniques; group two was shown early Greek pottery and engaged in a discussion of the works; and group three was asked questions to remind them of their own studio and past experiences working with clay to awaken their passive knowledge. The study then analyzed the ceramic vessels created by students in each group. The vessels were judged on their aesthetic qualities. A written pretest Big Ideas and Craftmaking: A Case for Use in Middle School Ceramics Elaina M. Fejes and a posttest were also given to students to measure knowledge gained in the process. The findings showed the first and second groups produced better quality vessels as well as gaining expanded knowledge of the ceramic process. The third group produced work of a lesser aesthetic quality and only marginally gained new knowledge of the ceramic process compared to the other two groups (Brewer& Colbert, 1992). The findings suggested that technical information and demonstration has a strong place in the development of craft. Discussing Greek pottery gave the students of group two a point of reference and connected what they made to a long human history of clay work. A critique of this study may include the fact that there was no investigation of the wider knowledge that the students in the third group may have obtained, such as meaning-making, problem solving and higher thinking strategies. In a middle school classroom setting, the approach chosen by a teacher should therefore be the right combination of teaching technique while considering meaning making for a comprehensive craft education. Researchers have further suggested that meaning comes from a variety of sources. Artists and students alike recognize that “materials have their own seductive powers and are [sic] part of the reason art can be so compelling. It is not often recognized that materials have the capacity to carry their own meanings… A pot made of clay carries very different meanings [compared to a pot made of other materials]. While the material begins organically and is technically alive in its wet state, fire and heat turn it into something hard, solid, and stable. Ideas about containers are connected to ideas about durability and permanency” (Simpson et al., 1998, p.83-85). This argument is significant because educators should know they may not need to force a big idea, theme, or context because meaning within a material is often innate. The development of a craft such as ceramics has more implications than only an exercise in technical skill. Students may initially find meaning by simply learning a new skill and connecting to their cultural heritage through craft. Later, these skills and connections may be expanded upon by allowing students to use an art form they find meaningful and apply it to creating meaning the way Walker (2003) and Sessions (1999) suggest. Under the umbrella of big ideas comes cultural heritage, community, Big Ideas and Craftmaking: A Case for Use in Middle School Ceramics Elaina M. Fejes collaboration, and service which when introduced to middle school students have the potential to foster life long meaning making through the creation of ceramics. “It takes time to get to know how to use the tools, to find out what a medium can do, and to begin to make some connection between the medium and the ideas it might carry” (Simpson et al., 1998 p. 86). When teaching a craft, such as ceramics, it is important to stress technique as well as meaning making. Moreover, in order to teach ceramics successfully, technical skills should be emphasized prior to incorporating big ideas. When both strategies for teaching a craft are incorporated into a curriculum, students will not only appreciate the craft as a skill-making endeavor, but also as an art form that expresses meaning making themes such as cultural heritage, community, collaboration, and service. Big Ideas and Craftmaking: A Case for Use in Middle School Ceramics Elaina M. Fejes Works Cited: Anderson, T., & McRorie, S. (1997). A role for aesthetics in centering the k-12 art curriculum. Art Education,50(3), 6-14. Brewer, T. M. (1991). An examination of two approaches to ceramic instruction in elementary education. Studies in Art Education, 32(4), 1991. Brewer, T. M., & Colbert, C. B. (1992). The effect of contrasting instructional strategies on seventh-grade students' ceramic vessels. Studies in Art Education, 34(1), 18-27. Brown, S. L. (2007). Using visual art as the bridge to our cultural heritage: Roy Strassber's Holocuast bone structures series. Art Education, 60(2), 25-32. Hagaman, S. (1990). The community of inquiry: An approach to collaborative learning. Studies in Art Education,31(3), 149-157. Sessions, B. (1999). Ceramics curriculum: What is taught? what is learned? how do we know?. Art Education,52(5), 6-11. Stephens, P. G. (2006). A real community bridge: Informing community-based learning through a model of participatory public art. Art Education, 59(2), 40-46. Simpson, J. W., et al. (1998).Creating meaning through art, teacher as choice-maker. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Taylor, P. G. (2002). Singing for someone else's supper. Art Education, 55(5), 46-52. Walker, S. R. (2003). Teaching meaning in artmaking. Worcester, MA: Davis Publications.