Comments on - Rutgers University

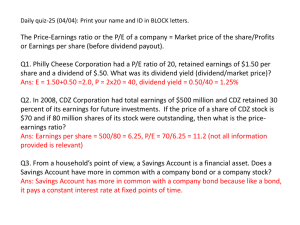

advertisement

Dividend Policy and Dividend Payment Behavior: Theory and Evidence Cheng-Few Lee Rutgers University Flow Chart of Dividend Policy and Dividend Behavior Dividend Policy Dividend Irrelevance Theory Dividend Relevance Theory without Tax Effect Empirical Work Theory Time-Series Dividend Relevance Theory with Tax Effect CAPM Approach Non-CAPM Approach Cross-Sectional 2 Flow Chart of Dividend Policy and Dividend Behavior Dividend Relevance Theory without Tax Effect Theory Empirical Work Time-Series Dividend Behavior Cross-Sectional Signaling Hypothesis Free Cash Flow Hypothesis Flexibility Hypothesis Life-Cycle Theory Price Multiplier Model Cov. btw ROE and g Partial Adjustment Process Information Content or Adaptive Expectations Myopic Dividend Policy Residual Dividend Policy 3 Empirical Analyses in Dividend Policy Research Descriptive Data Analysis Time Series Cross-Sectional Regression Analysis Time Series Probit / Logit Cross-Sectional Fama-MacBeth Procedure Panel Data Analysis Seemly Uncorrelated Regression (SUR) Fixed Effect Model 4 Dividend Policy and Dividend Payment Behavior A. Theory (i) Dividend irrelevance (M&M, 1961) and corner solution (DeAngelo and DeAngelo, 2006) (ii) Dividend relevance (Gordon, 1962; and Lintner, 1964) - A bird in hand theory (Bhatacharya, 1979) - Signaling theory (John & Williams, 1985; Miller & Rock, 1985; and Lee et al., 1993) - Free cash flow theory (Eastbrook,1984; Jensen, 1986; and Lang and Lizenberger,1989) - Financial flexibility theory (Jagannathan et al., 2000, DeAngelo and DeAngelo, 2006; Blau and Fuller, 2008) - Life-cycle theory (DeAngelo et al., 2006) 5 Dividend Policy and Dividend Payment Behavior B. Dividend Behavior Models (i) Partial Adjustment Model (Lintner, 1956 AER) D t a 0 a1 D t 1 a 2 E t et (1) Current earnings C E D a a D a CE e (1a) => Lintner’s model Permanent earnings P E Dt a 0 a1 Dt 1 a 2 PE t et (1b) => Lee and Primeaux (1991) and Lambrecht and Myers (2012) (ii) Mixed Partial Adjustment and Adapted Expectation (Fama & Babiak, 1968 JASA) (iii) Generalized Dividend Forecasting Model (Lee et al., 1987, Journal of Econometrics) t t 0 1 t 1 2 t t t D t a1 a 2 D t 1 a 3 D t 2 a 4 E t v t (2) w here a1 , a 2 2 , a 3 1 1 , a 4 r , and v t u t 1 u t 1 . 6 Dividend Policy and Dividend Payment Behavior C. Price Multiplier Model (i) Friend and Puckett (1964, AER) have proposed the relationship between stock prices, dividends, and retained earnings as follows: where Pti A B D ti C R ti i 1, ,N t 1, ,T (3 ) Pti , D ti , and R ti represtne price per share, dividen d per share and retained earnings per share, respectively. Based upon Eq. (1) and discount cash flow model in terms of optimal forecasting, Granger (1975 JF) has shown that B and C can be written in terms of discount rate, a1 , and a 2 of Eq. (1). Therefore, it can be concluded that Eq. (3) is a theoretical derived model instead of an ad-hoc model. (ii) Lee (1976, JF), Chang (1977, JFQA), and Gilmore and Lee (RES) have done empirical studies on price multiplier model. 7 Dividend Policy and Dividend Payment Behavior D. Integration of Dividend Policy and CAPM (Litzenberger and Ramaswamy, 1982) E ( R j) - rf A B j C (d j - rf ) A is the excess return on a zero-beta portfolio with a dividend yield equal to the riskless rate of interest, relative to the market portfolio. B is similar to the market-risk premium concept in the original CAPM. C represents a balancing of risks. The further discussion of Eq. (4) can be found in Litzenberger and Ramaswamy (1982) or Lee et al. (2009). 8 Outline 1. Introduction 2. The Model for Optimal Dividend Policy 3. Comparative Static Analysis of Dividend Payout Policy 3.1 Case I: Total Risk 3.2 Case II: Systematic Risk 3.3 Total Risk and Systematic Risk 3.4 No Change in Risk 3.5 Relationship between the Optimal Payout Ratio and the Growth Rate 4. Joint Optimization of Growth Rate and Payout Ratio 4.1 Optimal Growth Rate v.s. Time Horizon 4.2 Optimal Growth Rate v.s. Degree of Market Perfection 4.3 Optimal Growth Rate v.s. ROE 4.4 Optimal Growth Rate v.s. Initial Growth Rate 4.5 Optimal Dividend Policy v.s. Optimal Growth Rate 9 Outline 5. Dividend Behavior Model 5.1 Partial Adjustment Model (Lintner, 1956 AER) 5.2 Mixed Partial Adjustment and Adapted Expectation (Fama & Babiak, 1968 JASA) 5.3 Generalized Dividend Forecasting Model (Lee et al., 1987, Journal of Econometrics) 6. Empirical Evidence 6.1 Sample Description 6.2 Multivariate Analysis 6.3 Fama-MacBeth Analysis 6.4 Fixed Effect Analysis 7. Summary and Concluding Remarks 7.1 Limitations of cross-sectional approach to investigate dividend policy 7.2 We need to use dividend behavior model to supplement cross-sectional approach to obtain more meaningful conclusion for decision making. 10 Introduction Dividend Policy Miller and Modigliani (1961) - Firm Value is independent of dividend policy. - Assumptions of M&M theory 1) no tax. 2) no capital market frictions (i.e., no transaction cost, asset trade restriction, or bankruptcy cost) 3) firms and investors can borrow or lend at the same rate. 4) firm financial policy reveals no information. 5) only consider no payout and payout all free cash flow. DeAngelo and DeAngelo (2006) > M&M (1961) irrelevance result is “irrelevant” because it only considers payout policies that pay out all free cash flow. > Payout policy matters when partial payouts are allowed. 11 Introduction • • • Signaling Hypothesis - The signaling hypothesis suggests managers with better information than the market will signal this private information using dividends. - A company announcements of an increase in dividend payouts act as an indicator of the firm possessing strong future prospects. [Bhatacharya (1979), John and Williams (1985), Miller and Rock (1985), and Nissam and Ziv (2001)] Free Cash Flow Hypothesis (Agency Cost) - Dividend payment can reduce potential agency problem. [Eastbrook (1984), Jensen (1986), Lang and Lizenberger(1989), Lie (2000), and Grullon et al. (2002)] Financial Flexibility - Management trades off two aspects of Dividends. One is financial flexibility by not paying dividends. Another is deterioration on stock price if not paying dividends. 12 [Blau and Fuller (2008)] Introduction 1. Based on the DeAngelo & DeAngelo (2006) static analysis, we derive a theoratical dynamic model and show that there exists an optimal payout ratio under perfect market. 2. We derive the relationship between firm’s optimal payout ratio and its risks. 3. We derive the relationship between firm’s optimal payout ratio and its growth. 4. We further develop a fully dynamic model for determining the time optimal growth and dividend policy under the imperfect market, the uncertainty of the investment, and the dynamic growth rate. 5. We study the effects of the time-varying horizons, the degree of market perfection, and stochastic initial conditions in determining an optimal growth and dividend policy for the firm. 6. When the stochastic growth rate is introduced, the expected return may suffer a model specification. 7. Empirical evidence of the determination of the optimal payout policy. 13 The Model for Optimal Dividend Policy - Let r ( t ) represent the initial assets of the firm and h ( t ) represent the growth rate. Then, the earnings of this firm are given by Eq. (1), which is x (t ) r (t ) A ( o ) e ht - The retained earnings of the firm, y t , can be expressed as y (t ) x (t ) m (t ) d (t ) where is the number of shares outstanding, and d ( t ) is dividend per share at time t. m (t ) 14 The Model for Optimal Dividend Policy The new equity raised by the firm at time t can be defined as e (t ) p (t ) m (t ) where = degree of market perfection, 0 < 1. Therefore, the investment in period t can be written as: hA ( o ) e ht x (t ) m (t ) d (t ) m (t ) p (t ) Rearranging the equation above, we can get d (t ) r (t ) h A ( o ) e ht m (t ) p (t ) m (t ) 15 The Model for Optimal Dividend Policy - The stock price should equal the present value of this certainty equivalent dividend stream discounted at the cost of capital (k) of the firm. p (o ) T kt dˆ ( t ) e dt 0 ( A bI h ) A ( o ) e m ( t ) p ( t ) th T [ A ( o ) (t ) (t ) e 2 m (t ) 0 2 m (t ) 2 2 th ]e 2 kt dt - A differential equation can be formulated: p (t ) [ m (t ) k ] p (t ) G (t ) m (t ) where G (t ) ( a bI h ) A ( o ) e m (t ) th A ( o ) (t ) (t ) e 2 2 m (t ) 2 2 th 2 16 Optimal Dividend Policy Optimal Payout Ratio when 1 : 2 2 2 2 2 2 ( h k )( T t ) ( a bI h ) ( h ( t ) ( t ) ( t ) ( t ) ( t ) ( t ) )[ e 1] 1 2 2 x (t ) ( a bI ) (t ) (t ) ( h k ) D (t ) ( h k )( T t ) 2 2 ( a bI h ) [e 1] (t ) (t ) = 1 h 2 2 ( a bI ) (h k ) ( t ) ( t ) 17 Relationship between the Optimal Payout Ratio and the Growth Rate [ D ( t ) / x ( t )] h ( 1 a bI )[ k he ( h k )( T t ) hk k h h k (T t ) e ( h k )( T t ) k ] (1 ) 2 a bI h k h - The sign is not only affected by the growth rate (h), but is also affected by the expected rate of return on assets (a bI ), the duration of future dividend payments (T-t), and the cost of capital (k). - Sensitivity analysis shows that the relationship between the optimal payout ratio and the growth rate is generally negative. =>a firm with a higher rate of return on assets tends to payout less when its growth opportunities increase. 18 19 Relationship between the Optimal Payout Ratio and the Growth Rate [ D ( t ) / x ( t )] h When ( a bI ) h (T t ) h (T t ) 1 a bI 1 1 h ( a bI ) , there is a negative 2 (T t ) relationship between the optimal payout ratio and the growth rate. =>when a firm with a high growth rate or a low rate of return on assets faces a growth opportunity, it will decrease its dividend payout to generate more cash to meet such a new investment. 20 Implications Hypothesis 1: firms generally reduce their dividend payouts when their growth rates increase. The negative relationship between the payout ratio and the growth ratio in our theoretical model implies that high growth firms need to reduce the payout ratio and retain more earnings to build up “precautionary reserves,” while low growth firms are likely to be more mature and already build up their reserves for flexibility concerns. [Rozeff (1982), Fama and French (2001), Blau and Fuller (2008), etc.] 21 Optimal Payout Ratio vs. Total Risk D ( t ) / x ( t ) (t ) 2 2 ( t ) e ( h k )( T t ) 1 (1 ) a bI hk h High growth firms h a bI : negative relationship between optimal payout ratio and total risk. Low growth firms h a bI : positive relationship between optimal payout ratio and total risk 22 Optimal Payout Ratio vs. Systematic Risk D ( t ) / x ( t ) (t ) 2 2 ( t ) e ( h k )( T t ) 1 (1 ) a bI hk h High growth firms h a bI : negative relationship between optimal payout ratio and systematic risk. Low growth firms h a bI : positive relationship between optimal payout ratio and systematic risk 23 Implications • Hypothesis 2: the relationship between the firms’ dividend payouts and their risks is negative when their growth rates are higher than their rates of return on asset. - Flexibility Hypothesis High growth firms need to reduce the payout ratio and retain more earnings to build up “precautionary reserves.” These reserves become more important for a firm with volatile earnings over time. => For flexibility concerns, high growth firms tend to retain more earnings when they face higher risk. 24 Implications • Hypothesis 3: the relationship between the firms’ dividend payouts and their risks is positive when their growth rates are lower than their rates of return on asset. - Free Cash Flow Hypothesis 1. Low growth firms are likely to be more mature and most likely already built such reserves over time. 2. They probably do not need more earnings to maintain their low growth perspective and can afford to increase the payout [see Grullon et al. (2002)]. 3. The higher risk may involve higher cost of capital and make free cash flow problem worse for low growth firms. => For free cash flow concerns, low growth firms tend to pay more dividends when they face higher risk 25 Optimal Payout Ratio vs. Total Risk and Systematic Risk d [ D ( t ) / x ( t )] d ( where (1 (t ) 2 (t ) 2 h a bI )[ e )d( ( h k )( T t ) hk (t ) 2 (t ) 2 1 ) ] • Relative effect on the optimal dividend payout ratio d[ (t ) 2 (t ) 2 ] d[ (t ) 2 (t ) 2 ] (30) 26 Optimal Payout Ratio when No Change in Risk [ D ( t ) / x ( t )] (1 h a bI )[ k he ( h k )( T t ) hk ] When there is no change in risk, the optimal payout ratio is identical to the optimal payout ratio of Wallingford (1972). 27 Joint Optimization of Growth Rate and Payout Ratio • The new investment at time t is dA t dt A t t g t A o e o g s ds Y t D t n t p (t ) L A t Retained Earnings New Equity where New Debt D t the total dollar dividend at tim e t ; p t price per share at tim e t ; degree of m arket perfections, 0 < l; n t P t the proceeds of new equity issued at tim e t ; L = th e d eb t to to tal assets ratio 28 Joint Optimization of Growth Rate and Payout Ratio • The model defined in previous slide is for the convenience purpose. If we want the company’s leverage ratio unchanged after the expansion of assets then we need to modify the equation as t A t g t A o e o g s ds Y t D t n t p ( t ) 1 D / E Y t D t n t p ( t ) we can obtain the growth rate as g (t ) Our Model R O E 1 d 1 R O E 1 d n t p t / E 1 R O E 1 d Higgins’ sustainable g which is the generalized version of Higgins’ (1977) sustainable growth rate model. Our model shows that Higgins’ (1997) sustainable growth rate is under-estimated due to the omission of the source of the growth related to new equity issue which is the second term of our model. 29 Joint Optimization of Growth Rate and Payout Ratio Discount cash flow p o T 0 kt dˆ t e dt The price per share can be expressed as PV of future dividends with a risk adjustment. p o 1 n o T 0 1 2 0 g s ds n t r t g t A o e a A o Future Dividends t 2 t n t 2 0 g s ds kt e e dt t 2 Risk Adj. => maximize p(o) by jointly determine g(t) and n(t). 30 Optimal Growth Rate g * t r r rt 1 1 e go 2 gor go r go e rt 2 Logistic Equation – Verhulst (1845) => a convergence process 31 Case I: Optimal Growth Rate v.s. Time Horizon g * t g t * t r r r t r 1 e go 2 W hen g 0 r , g * t 0. W hen g 0 r , g * t 0. * t 0. W hen g 0 r , g r r t 1 1 e go 2 2 2 32 Case I: Optimal Growth Rate v.s. Time Horizon Convergence Process - Firms with different initial growth rates all tend to converge to their target rates (ROE). 33 Case II: Optimal Growth Rate v.s. Degree of Market Perfection g * t If the m arket is m ore perfect r r t 1 e go 2 rt 2 2 r r t 1 1 e go 2 2 2 is larger , the speed of convergence is faster. 34 Case II: Optimal Growth Rate v.s. Degree of Market Perfection 35 Case III: Optimal Growth Rate v.s. ROE g * t r rt go go 1 e 2 g r o g r g e rt o o t 2 2 re rt 2 2 When initial growth rate is lower than the target rate (ROE), positive. g * t r is => If the target rate (ROE) is higher, the adjustment process will be faster. 36 Case IV: Optimal Growth Rate v.s. Initial Growth Rate 2 g * t g o g * t g o r rt e go 2 r rt 1 1 e go 2 2 is always positive. => The higher initial growth rate is, the higher optimal growth rate at each time. 37 38 Optimal Dividend Payout Ratio D t Y t * g t 1 r t t kt 0 g * s ds e 1 where W T e s 0 g * u du ks t 2 s 2 t 2 t g * t r 2 2 t 1 r g * s g * r g t 2 t g * t * t 3 W 2 ds • Assuming 1 an d g * t g * , ( g k )( T t ) 2 e 1 D t g (t ) * 1 1 g * 2 Y t r t (g k ) (t ) * * - Wallingford (1972), Lee et al. (2010) 39 Optimal Dividend Payout Ratio v.s. Growth Rate [ D ( t ) / Y ( t )] g ( * 1 r t k g e * )[ * ( g k )( T t ) g k * k g * g * k (T t ) e ( g g ] (1 ) 2 * r t g k * * k )( T t ) k r ( t ) g * (T t ) g * (T t ) 1 * r (t ) g The relationship between optimal dividend payout and growth rate is negative in general cases. 40 Stochastic Growth Rate and Specification Error dA t dt t A t g t A o e o g s ds Y t D t n t p ( t ) LA t Retained Earnings New Equity New Debt When a stochastic growth rate is introduced, g t N g t , g t 2 41 Stochastic Growth Rate and Specification Error 0 g s ds g s ds 0 g s ds n t p t C ov r t , A o e 0 E t e r t g t A o e E d t n t n t t t t g s ds If C ov r t , A o e 0 is positive, d t in the previous analysis t is overestim ated. 42 Hypotheses Development • Hypothesis 1: The firm’s growth rate follows a mean-reverting process. H1a: There exists a target rate of the firm’s growth rate, and the target rate is the firm’s return on equity. H1b: The firm partially adjusts its growth rate to the target rate. H1c: The partial adjustment is fast in the early stage of the mean-reverting process. • Hypothesis 2: The firm’s dividend payout is negatively associated with the covariance between the firm’s rate of return on equity and the firm’s growth rate. H2a: The covariance between the firm’s rate of return on equity and the firm’s growth rate is one of the key determinants of the dividend payout policy. 43 Hypotheses Development • Hypothesis 3: The firm tends to pay a dividend if its covariance between the firm’s rate of return on equity and the firm’s growth rate is lower. H3a: The firm tends to stop paying a dividend if its covariance between the firm’s rate of return on equity and the firm’s growth rate is higher. H3b: The firm tends to start paying a dividend if its covariance between the firm’s rate of return on equity and the firm’s growth rate is lower. 44 Sample • Stock price, stock returns, share codes, and exchange codes are CRPS. Firm information, such as total asset, sales, net income, and dividends payout , etc., is collected from COMPUSTAT. • The sample period is from 1969 to 2008. • Only common stocks (SHRCD = 10, 11) and firms listed in NYSE, AMEX, or NASDAQ (EXCE = 1, 2, 3, 31, 32, 33) are included. • Utility firms and financial institutions (SICCD = 4900-4999, 60006999) are excluded. • For the purpose of estimating their betas to obtain systematic risks, firm years in our sample should have at least 60 consecutively previous monthly returns. 45 Summary Statistics of Sample Firm Characteristics 46 46 Summary Statistics of Sample Firm Characteristics 47 Multivariate Regression payout ratio i , t ln 1 payout ratio i , t 1 Risk i , t 2 D i , t g RO A Risk i , t 3 G row th _ O ption i , t 4 ln( Size ) i , t Fixed Effect D um m ies ei Flexibility Hypothesis FCF Hypothesis 48 48 Empirical Results – Mean Reverting Process of firms’ growth rates 49 Partial Adjustment Model for the Growth Rate If t, j 1 => partial adjustment 50 Cov. is negatively related to the dividend payouts 51 The higher of the Cov., the higher possibility to stop the cash dividends. 52 Conclusion - 1 • We derive an optimal payout ratio using an exponential utility function to derive the stochastic dynamic dividend policy model. - Different from M&M model, our model considers 1) partial payout; 2)uncertainty (risks); 3) stochastic earnings. • A negative relationship between the optimal dividend payout ratio and the growth rate. • The relationship between firm’s optimal payout ratio and its risks depends on its growth rate relative to its ROA. - high growth firms pay dividends due to the consideration of flexibility and low growth firms pay dividends due to the 53 consideration of free cash flow problem. Conclusion - 2 • We derive a dynamic model of optimal growth rate and payout ratio which allows a firm to finance its new assets by retained earnings, new debt, and new equity. • The optimal growth rate follows a convergence processes, and the target rate is firm’s expected ROE. • The firm’s dividend payout is negatively associated with the covariance between the firm’s rate of return on equity and the firm’s growth rate. • The firm tends to pay a dividend if its covariance between the firm’s rate of return on equity and the firm’s growth rate is lower. 54 Potential Future Research 1. Time-series v.s. cross-sectional research 2. Relationship among discount cash flow, dividend partial adjustment model, and price multiplier model 3. Tax effect on dividend policy in terms of CAPM with dividend Effect 4. Limitations of cross-sectional approach to investigate dividend policy 5. We need to use dividend behavior model to supplement crosssectional approach to obtain more meaningful conclusion for decision making. 6. The impacts of Integrated Tax System can be further explored. 55 References - 1 Anderson, T. W., 1994, Statistical Analysis of Time Series (John Wiley and Sons, Inc., New York, NY). Andres, C., A. Betzer, M. Goergen, and L. Renneboog, 2009, Dividend policy of German firms: A panel data analysis of partial adjustment models, Journal of Empirical Finance, 16, 175-187. Agrawal, A., and N. Jayaraman, 1994, The dividend policies of all-equity firms: A direct test of the free cash flow theory, Managerial & Decision Economics 15, 139-148. Aivazian, V., L. Booth, and S. Cleary, 2003, Do emerging market firms follow different dividend policies from U.S. firms? Journal of Financial Research 26, 371-387. Akhigbe, A., S. F. Borde, and J. Madura, 1993, Dividend policy and signaling by insurance companies, Journal of Risk & Insurance 60, 413-428. Aoki, M.,1967, Optimization of Stochastic Systems (Academic Press, New York, NY). Astrom, K. J., 2006, Introduction to Stochastic Control Theory (Dover Publications, Mineola, NY). Asquith, P., and D. W. Mullins Jr., 1983, The impact of initiating dividend payments on shareholders' wealth, Journal of Business 56, 77-96. Baker, H. K., and G. E. Powell, 1999, How corporate managers view dividend policy, Quarterly Journal of Business & Economics 38, 17-35. Baker, M., and J. Wurgler, 2004a, A catering theory of dividends, Journal of Finance, 59, 1125-1165. Baker, M., and J. Wurgler, 2004b, Appearing and disappearing dividends: The link to catering incentives, Journal of Financial Economics, 73, 271-288. Bar-Yosef, S., and R. Kolodny, 1976, Dividend policy and capital market theory, Review of Economics & Statistics 58, 181-190. Bellman, R., 1990, Adaptive Control Process: A Guided Tour (Princeton University Press, Princeton, 56 NJ). References - 2 Bellman, R., 2003, Dynamic Programming (Dover Publication, Mineola, NY). Benartzi, S., R. Michaely, and R. Thaler, 1997, Do changes in dividends signal the future or the past? Journal of Finance 52, 1007-1034. Bernheim, B. D., and A. Wantz, 1995, A tax-based test of the dividend signaling hypothesis, American Economic Review 85, 532-551. Bhattacharya, S., 1979, Imperfect information, dividend policy, and “the bird in the hand” fallacy, Bell Journal of Economics 10, 259-270. Black, F., and M. Scholes, 1974, The effects of dividend yield and dividend policy on common stock prices and returns, Journal of Financial Economics 1, 1-22. Blau, B. M., and K. P. Fuller, 2008, Flexibility and dividends, Journal of Corporate Finance 14, 133152. Boehmer E., C. M. Jones, and X. Zhang, 2010, Shackling short sellers: The 2008 shorting ban, Working paper. Brennan, M. J., 1973, An approach to the valuation of uncertain income streams, Journal of Finance 28, 661-674. Brennan, M. J., 1974, An inter-temporal approach to the optimization of dividend policy with predetermined investments: Comment, Journal of Finance 29, 258-259. Brook, Y., W. T. Charlton, Jr., and R. J. Hendershott, 1998, Do firms use dividends to signal large future cash flow increases? Financial Management 27, 46-57. Cameron, A. C., J. B. Gelbach, and D. L. Miller,2006, Robust inference with multiway Clustering, Working paper. 57 References - 3 Chen, H. Y., M. C. Gupta, A. C. Lee, and C. F. Lee, 2012, Sustainable growth rate, optimal growth rate, and optimal payout ratio: A joint optimization approach, Journal of Banking and Finance, forthcoming. Chiang, A.C, 1984, Fundamental Methods of Mathematical Economics, 3rd ed. (McGraw-Hill, New York, NY). Chow, G. C., 1960, Tests of equality between Sets of coefficients in two linear regressions, Econometrica 28, 591-605. DeAngelo, H., and L. DeAngelo, 2006, The irrelevance of the MM dividend irrelevance theorem, Journal of Financial Economics 79, 293-315. DeAngelo, H., L. DeAngelo, and D. J. Skinner, 1996, Reversal of fortune: Dividend signaling and the disappearance of sustained earnings growth, Journal of Financial Economics 40, 341-371. DeAngelo, H., L. DeAngelo, and D. J. Skinner, 2004, Are dividends disappearing? Dividend concentration and the consolidation of earnings, Journal of Financial Economics, 72, 425-456. DeAngelo, H., L. DeAngelo, and R. M. Stulz, 2006, Dividend policy and the earned/contributed capital mix: A test of the life-cycle theory, Journal of Financial Economics 81, 227-254. Denis, D. J., D. K. Denis, and A. Sarin, 1994, The Information Content of Dividend Changes: Cash Flow Signaling, Overinvestment, and Dividend Clienteles, Journal of Financial & Quantitative Analysis 29, 567-587. Denis, D. J., and I. Osobov, 2008, Why do firms pay dividends? International evidence on the determinants of dividend policy, Journal of Financial Economics 89, 62-82. Dittmar, A. K., and R. F. Dittmar, 2008, The timing of financing decisions: An examination of the 58 correlation in financing waves, Journal of Financial Economics, 90, 59-83. References - 4 Easterbrook, F. H., 1984, Two agency-cost explanations of dividends, American Economic Review 74, 650-659. Fama, E. F., and H. Babiak, 1968, Dividend policy: An empirical analysis, Journal of the American Statistical Association, 63, 1132-1161. Fama, E. F., and K. R. French, 2001, Disappearing dividends: Changing firm characteristics or lower propensity to pay? Journal of Financial Economics 60, 3-43. Fama, E. F., and J. D. MacBeth, 1973, Risk, return, and equilibrium: empirical tests, Journal of Political Economy 81, 607-636. Fenn, G. W., and N. Liang, 2001, Corporate payout policy and managerial stock incentives, Journal of Financial Economics 60, 45-72. Flannery, M. J., and K. P. Rangan, 2006, Partial adjustment toward target capital structures, Journal of Financial Economics, 79, 469-506. Gabudean, R. C., 2007, Strategic interaction and the co-determination of firms financial policies, Working Paper. Gordon, M. J., 1962, The savings investment and valuation of a corporation, Review of Economics and Statistics 44, 37-51. Gordon, M. J., 1963, Optimal investment and financing policy, Journal of Finance 18, 264-272. Gordon, M. J., and E. F. Brigham, 1968, Leverage, dividend policy, and the cost of capital.” Journal of Finance, 23, 85-103. Gould, J. P., 1968, Adjustment costs in the theory of investment of the firm, Review of Economic Studies 35, 47-55. 59 References - 5 Grullon, G., R. Michaely, and B. Swaminathan, 2002, Are dividend changes a sign of firm maturity? Journal of Business 75, 387-424. Gujarati, D. N., 2009, Basic Econometrics, 5th ed. (McGraw-Hill, New York, NY). Gupta, M. C., and D. A. Walker, 1975, Dividend disbursal practices in commercial banking, Journal of Financial & Quantitative Analysis 10, 515-529. Hamilton, J. D., 1994, Time Series Analysis, 1st ed. (Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ). Hansen, B. E., 1996, Inference when a nuisance parameter is not identified under the null hypothesis, Econometrica 64, 413-430. Hansen, B. E., 1999, Threshold effects in nondynamic panels: Estimation, testing, and inference. Journal of Econometrics 93, 345-368. Hansen, B. E., 2000, Sample splitting and threshold estimation, Econometrica 68, 575-603, 2000. Healy, P. M., and K. G. Palepu, 1988, Earnings information conveyed by dividend Initiations and omissions, Journal of Financial Economics 21, 149-175. Higgins, R. C., 1974, Growth, dividend policy and cost of capital in the electric utility industry, Journal of Finance 29, 1189-1201. Higgins, R. C., 1977, How much growth can a firm afford? Financial Management 6, 7-16. Higgins R. C., 1981, Sustainable growth under Inflation, Financial Management 10, 36-40. Higgins R. C., 2008, Analysis for financial management, 9th ed. (McGraw-Hill, Inc, New York, NY). Hogg, R. V., and A. T. Craig, 2004, Introduction to mathematical statistics, 6th ed. (Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ). 60 References - 6 Howe, K. M., J. He, and G. W. Kao, 1992, One-time cash flow cash and free cash-flow Theory: Share Repurchases and special dividends, Journal of Finance 47, 1963-1975. Huang, R., and J. R. Ritter, 2009, Testing theories of capital structure and estimating the speed of adjustment, Journal of Financial Quantitative Analysis, 44, 237-271. Intriligator, M. D., 2002, Mathematical 0ptimization and Economic Theory (Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, Philadelphia, PA). Jagannathan, M., C. P. Stephens, and M. S. Weisbach, 2000, Financial flexibility and the choice between dividends and stock repurchases, Journal of Financial Economics 57, 355-384. Jensen, G. R., D. P. Solberg, and T. S. Zorn, 1992, Simultaneous determination of insider ownership, debt, and dividend policies, Journal of Financial & Quantitative Analysis 27, 247-263. Jensen, M. C., 1986, Agency costs of free cash flow, corporate finance, and takeovers, American Economic Review 76, 323-329. John, K., and J. Williams, 1985, Dividends, dilution, and taxes: A signaling equilibrium, Journal of Finance 40, 1053-1070. Kalay, A., and U. Loewenstein, 1986, The informational content of the timing of dividend announcements, Journal of Financial Economics 16, 373-388. Kalay, A., and R. Michaely, 1993, Dividends and taxes: A reexamination, Working Paper. Kao, C., and C. Wu, 1994, Tests of dividend signaling using the March-Merton model: A generalized friction approach, Journal of Business 67, 45-68. Kreyszig, E., 2010, Advanced engineering mathematics, 10th ed. (Wiley, New York, NY). Lang, L. H. P., and R. H. Litzenberger, 1989, Dividend announcements: Cash flow signaling vs. free cash 61 flow hypothesis? Journal of Financial Economics 24, 181-191. References - 7 Lee, C. F., M. C. Gupta, H. Y. Chen, and A. C. Lee., 2011, Optimal Payout Ratio under Uncertainty and the Flexibility Hypothesis: Theory and Empirical Evidence, Journal of Corporate Finance 17, 483501. Lee, C. F., and J. Shi, 2010, Application of alternative ODE in finance and econometric research, in Cheng F. Lee, Alice. C. Lee, and John Lee, ed.: Handbook of Quantitative Finance and Risk Management (Springer), 1293-1300. Lee, Cheng F., C. Wu, and M. Djarraya, 1987, A further empirical investigation of the dividend adjustment process, Journal of Econometrics 35, 267-285. Lerner, E. M., and W. T. Carleton, 1966a, Financing decisions of the firm, Journal of Finance 21, 202-214. Lerner, E. M., and W. T. Carleton, 1966b, A Theory of Financial Analysis (Harcourt, Brace & World, New York, NY). Lemmon, M. L., M. R. Roberts, and J. F. Zender, 2008, Back to the beginning: Persistence and the crosssection of corporate capital structure, Journal of Finance, 63, 1575-1608. Lie, E., 2000, Excess funds and agency problems: An empirical study of incremental cash disbursements, Review of Financial Studies 13, 219-248. Lintner, J., 1962, Dividends, earnings, leverage, stock prices and the supply of capital to corporations, Review of Economics and Statistics 44, 243-269. Lintner, J., 1963, The cost of capital and optimal financing of corporate growth, Journal of Finance 18, 292-310. Lintner, J., 1964, Optimal dividends and corporate growth under uncertainty, Quarterly Journal of Economics 78, 49-95. 62 References - 8 Lintner, J., 1965, Security prices, risk, and maximal gains from diversification, Journal of Finance 20, 587-615. Litzenberger, R. H., and K. Ramaswamy, 1979, The effects of personal taxes and dividends on capital asset prices: Theory and empirical evidence, Journal of Financial Economics 7, 163-195. Miller, M. H., and F. Modigliani, 1961, Dividend policy, growth, and the valuation of shares, Journal of Business 34, 411-433. Miller, M. H., and F. Modigliani, 1966, Some Estimates of the Cost of Capital to the Electric Utility Industry, 1954-57, American Economic Review 56, 333-391. Miller, M. H., and K. Rock, 1985, Dividend policy under asymmetric information, Journal of Finance 40, 1031-1051. Mossin, J., 1966, Equilibrium in a capital asset market, Econometrica 34, 768-783. Nissim, D., and A. Ziv, 2001, Dividend changes and future profitability, Journal of Finance 56, 21112133. Opler, T., and S. Titman, 1993, The determinants of leveraged buyout activity: Free cash flow vs. financial distress costs, Journal of Finance 48, 1985-1999. Parzen E., 1999, Stochastic Processes (Society for Industrial Mathematics, Philadelphia, PA). Petersen, M. A., 2009, Estimating standard errors in finance panel data sets: comparing approaches, Review of Financial Studies 22, 435-480. Pratt, J. W., 1964, Risk aversion in the small and in the large, Econometrica 32, 122-136. Rozeff, M. S., 1982, Growth, beta and agency costs as determinants of dividend payout ratios, Journal of Financial Research 5, 249-259. Sharpe, W. F., 1964, Capital asset prices: A theory of market equilibrium under conditions of risk, 63 Journal of Finance 19, 425-442. References - 9 Simon, H. A., 1956, Dynamic programming under uncertainty with a quadratic criterion function, Econometrica 24, 74-81. Smith Jr., C. W., and R. L. Watts, 1992, The investment opportunity set and corporate financing, dividend, and compensation policies, Journal of Financial Economics 32, 263-292. Theil, H., 1957, A note on certainty equivalence in dynamic planning, Econometrica 25, 346-349. Thompson, S. B., 2010, Simple formulas for standard errors that cluster by both firm and time, Working paper. Verhulst, P. F., 1845, Recherches mathématiques sur la loi d'accroissement de la population, Nouv. mém. de l'Academie Royale des Sciences et Belles-Lettres de Bruxelles 18, 1-41. Verhulst, P. F., Deuxième mémoire sur la loi d'accroissement de la population, Mém. de l'Academie Royale des Sciences, des Lettres et des Beaux-Arts de Belgique 20, 1-32. Wallingford, II, B. A., 1972a, An inter-temporal approach to the optimization of dividend policy with predetermined investments, Journal of Finance 27, 627-635. Wallingford, II, B. A., 1972b, A correction to “An inter-temporal approach to the optimization of dividend policy with predetermined investments,” Journal of Finance 27, 944-945. Wallingford, II, B. A., 1974, An inter-temporal approach to the optimization of dividend policy with predetermined investments: Reply, Journal of Finance 29, 264-266. Yoon, P. S., and L. T. Starks, 1995, Signaling, investment opportunities, and dividend announcements, Review of Financial Studies 8, 995-1018. Zeileis, A., F. Leisc., K. Hornik., and C. Kleiber, 2002, strucchange: An R package for testing for structural change in linear regression models, Journal of Statistical Software 7, 1-38. 64