PROCESS SELECTION,

DESIGN, AND ANALYSIS

CHAPTER 7

DAVID A. COLLIER AND JAMES R. EVANS

OM3 Chapter 7 Process Selection, Design, and Analysis

© 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be scanned, copied or duplicated, or posted to a publicly accessible website, in whole or in part.

1

Process Choice Decisions

Process design is an important operational

decision that affects the cost of operations,

customer service, and sustainability.

2

Process Choice Decisions – Types of Goods and

Services

• Custom, or make-to-order, goods and

services are generally produced and delivered as

one-of-a-kind or in small quantities, and are

designed to meet specific customers’

specifications.

Examples include ships, weddings, certain

jewelry, estate plans, buildings, and surgery.

3

Process Choice Decisions – Types of Goods and

Services

• Option, or assemble-to-order, goods and

services are configurations of standard parts,

subassemblies, or services that can be selected by

customers from a limited set.

Examples are Dell computers, Subway

sandwiches, machine tools, and travel agent

services.

4

Process Choice Decisions – Types of Goods and

Services

• Standard, or make-to-stock, goods and

services are made according to a fixed design,

and the customer has no options from which to

choose.

Examples are appliances, shoes, sporting

goods, credit cards, online Web-based

courses, and bus service.

5

Process Choice Decisions – Types of Processes

• Projects are large-scale, customized initiatives that

consist of many smaller tasks and activities that

must be coordinated and completed to finish on

time and within budget.

Characteristics: One-of-a-kind, large scale,

complex, resources brought to site; wide

variation in specs and tasks.

Examples: Legal defense preparation,

construction, customer jewelry, consulting, and

software development.

6

Process Choice Decisions – Types of Processes

• Job shop processes are organized around particular

types of general-purpose equipment that are flexible

and capable of customizing work for individual

customers.

Characteristics: Significant setup and/or changeover time, batching,

low to moderate volume, many routes, many different products, high

work-force skills, and customized to customer’s specs.

Examples: Many small manufacturing companies are set up as job

shops, as are hospitals, legal services, and some restaurants.

7

Process Choice Decisions – Types of Processes

• Flow shop processes are organized around a fixed

sequence of activities and process steps, such as

an assembly line, to produce a limited variety of

similar goods or services.

Characteristics: Little or no setup time, dedicated to small range of

goods or services that are similar, similar sequence of process steps,

moderate to high volume.

Examples: Assembly lines that produce automobiles and appliances,

production of insurance policies and checking account statements, and

hospital laboratory work.

8

Process Choice Decisions – Types of Processes

• A continuous flow process creates highly

standardized goods or services, usually around the

clock in very high volumes.

Characteristics: Very high volumes in a fixed

processing sequence, high investment in system,

24-hour/7-day continuous operation, automated,

dedicated to a small range of goods or services.

Examples: Chemical, gasoline, paint, toy, steel

factories; electronic funds transfer, credit card

authorizations, and automated car wash.

9

Process Choice Decisions

•

A product life cycle is a characterization of product

growth, maturity, and decline over time.

Four phases:

•

Introduction

Growth

Maturity

Decline and turnaround

A product’s life cycle has important implications in terms of process design

and choice. For example, new products with low sales volume might be

produced in a job shop process; however, as sales grow and volumes

increase, a flow shop process might be more efficient.

10

The Product-Process Matrix

• The product-process matrix is a model that

describes the alignment of process choice with

the characteristics of the manufactured good.

The most appropriate match between type of

product and type of process occurs along the

diagonal in the product-process matrix.

As one moves down the diagonal, the emphasis

on both product and process structure shifts from

low volume and high flexibility, to higher volumes

and more standardization.

11

Exhibit 7.1

Characteristics

of Different

Process Types

12

Exhibit 7.2

Product-Process Matrix

13

The Service-Positioning Matrix

•

•

In the product-process matrix, product volume, the

number of products, and the degree of

standardization/customization determine the

manufacturing process that should be used. This

relationship between volume and process is not found in

many service businesses.

The Service-Positioning Matrix is similar to the productprocess matrix in that it suggests that the nature of the

customer’s desired service encounter activity sequence

should lead to the most appropriate service system design

and that superior performance results by generally staying

along the diagonal of the matrix.

14

The Service-Positioning Matrix

• A pathway is a unique route through a service

system. Pathways can be customer- or

provider-driven, depending on the level of

control that the service firm wants to ensure.

• The service encounter activity sequence

consists of all the process steps and associated

service encounters necessary to complete a

service transaction and fulfill customer’s wants

and needs.

15

The Service-Positioning Matrix

• Customer-routed services are those that offer

customers broad freedom to select the

pathways that are best suited for their

immediate needs and wants, from many

possible pathways through the service delivery

system.

Examples include searching the Internet,

museums, health clubs, and amusement

parks.

16

The Service-Positioning Matrix

• Provider-routed services constrain customers to

follow a very small number of possible and

predefined pathways through the service system.

Examples are a newspaper dispenser and

logging on to a secure online bank account.

17

Exhibit 7.3

The Service

Positioning Matrix

Source: Adapted from D. A.

Collier and S. M. Meyer, “A

Service Positioning Matrix,”

International Journal of

Production and Operations

Management, 18, no. 12, 1998,

pp. 1123–1244. Also see D. A.

Collier and S. Meyer, “An

Empirical Comparison of Service

Matrices,” International Journal of

Operations and Production

Management, 2000 (no. 5–6), pp.

705–729.

18

Process Design – Four Levels of Work

• Task—a specific unit of work required to create

an output.

• Activity—a group of tasks (sometimes called a

workstation) needed to create and deliver an

intermediate or final output.

• Process—a group of activities.

• Value chain—a network of processes.

19

Exhibit 7.4 The Hierarchy of Work and Cascading Flowcharts for Antacid Tablets

20

Process and Value Stream Mapping

•

A process map (flowchart) describes the sequence of all

process activities and tasks necessary to create and

deliver a desired output or outcome.

•

Process maps document how work either is, or should be, accomplished,

and how the transformation process creates value.

A process boundary is the beginning or end of a process.

Makes it easier to obtain management support, assign process

ownership, and identify where performance measures should be taken.

21

Process and Value Stream Mapping

• In service applications, flowcharts generally

highlight the points of contact with the customer

and are often called service blueprints or service

maps.

• Such flowcharts often show the separation

between the back office and the front office with

a “line of customer visibility.”

22

Process and Value Stream Mapping

• The value stream refers to all value-added activities

involved in designing, producing, and delivering

goods and services to customers.

• A value stream map (VSM) shows the process flows

in a manner similar to an ordinary process map;

however, the difference lies in that value stream

maps highlight value-added versus non-value-added

activities and include costs associated with work

activities for both value- and non-value-added

activities.

23

Process and Value Stream Mapping

Examples of non-value-added activities include:

• Transferring materials between two nonadjacent

workstations

• Overproducing

• Waiting for service or work to do

• Not doing work correctly the first time

• Requiring multiple approvals for a low cost

electronic transaction

24

Exhibit 7.6 Restaurant Order Posting and Fulfillment Process

25

Process Design Methodology

1. Define the purpose and objectives of the process.

2. Create a detailed process or value stream map that

describes how the process is currently performed.

3. Evaluate alternative process designs.

4. Identify and define appropriate performance

measures for the process.

5. Select the appropriate equipment and technology.

6. Develop an implementation plan to introduce the

new or revised process design.

26

Process Mapping Improves Pharmacy Service

Metro Health Hospital in Grand Rapids, Michigan, applied

process mapping reducing the lead time for getting the first

dose of a medication to a patient in its pharmacy services

operations. The lead time was measured from the time an

order arrived at the pharmacy to its delivery on the

appropriate hospital floor. A process improvement team

carefully laid out all the process steps involved and found

that it had a 14-stage process with some unnecessary steps,

resulting in a total lead time of 166 minutes.

(continued)

27

Process Mapping Improves Pharmacy Service

During the evaluation process, the pharmacy calculated that

technicians were spending 77.4 percent of their time

locating products; when a pharmacist needed a technician

for clinical activities, the technician was usually off searching

for a drug. Overall, the pharmacy at Metro realized a 33percent reduction in time to get medications to patients,

and reduced the number of process steps from 14 to nine

simply by removing non-value-added steps. Patients have

experienced a 40-percent reduction in pharmacy-related

medication errors, and the severity of those errors has

decreased.

28

Process Analysis and Improvement

Strategies:

•

•

•

•

•

•

Increasing revenue by improving process efficiency in creating

goods and services and delivery of the customer benefit

package.

Increasing agility by improving flexibility and response to

changes in demand and customer expectations.

Increasing product and/or service quality by reducing defects,

mistakes, failures, or service upsets.

Decreasing costs through better technology or elimination of

non-value-added activities.

Decreasing process flow time by reducing waiting time or

speeding up movement through the process and value chain.

Decreasing the carbon footprint of the task, activity, process

and/or value chain.

29

Process Analysis and Improvement

Questions to ask for process analysis:

•

•

•

•

Are the steps in the process arranged in logical

sequence?

Do all steps add value? Can some steps be eliminated

and should others be added in order to improve quality or

operational performance? Can some be combined?

Should some be reordered?

Are capacities of each step in balance; that is, do

bottlenecks exist for which customers will incur excessive

waiting time?

What skills, equipment, and tools are required at each

step of the process? Should some steps be automated?

30

Process Analysis and Improvement

•

•

•

•

At which points in the system (sometimes called process

fail points) might errors occur that would result in

customer dissatisfaction, and how might these errors be

corrected?

At which point or points in the process should

performance be measured? What are appropriate

measures?

Where interaction with the customer occurs, what

procedures, behaviors, and guidelines should employees

follow that will present a positive image?

What is the impact of the process on sustainability? Can

we quantify the carbon footprint of the current process?

31

Process Analysis and Improvement

• Reengineering has been defined as “the

fundamental rethinking and radical redesign of

business processes to achieve dramatic

improvements in critical, contemporary measures

of performance, such as cost, quality, service,

and speed.”

32

Process Design and Resource Utilization

• Utilization is the fraction of time a workstation or

individual is busy over the long run.

Utilization (U) =

Resources Used

[7.1]

Resources Available

or

Utilization (U) =

Demand Rate

[Service Rate × Number

of Servers]

[7.2]

33

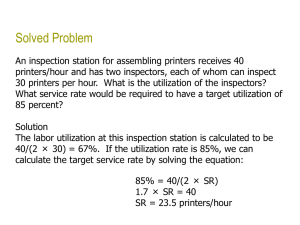

Solved Problem

An inspection station for assembling printers receives 40

printers/hour and has two inspectors, each of whom can inspect

30 printers per hour. What is the utilization of the inspectors?

What service rate would be required to have a target utilization of

85 percent?

Solution

The labor utilization at this inspection station is calculated to be

40/(2 × 30) = 67%. If the utilization rate is 85%, we can

calculate the target service rate by solving the equation:

85% = 40/(2 × SR)

1.7 × SR = 40

SR = 23.5 printers/hour

34

Process Design and Resource Utilization

• The average number of entities completed per unit time—

the output rate—from a process is called throughput.

–

•

Throughput might be measured as parts per day, transactions per

minute, or customers per hour, depending on the context.

A bottleneck is the work activity that effectively limits throughput of the

entire process.

–

Identifying and breaking process bottlenecks is an important part of

process design and improvement, and will increase the speed of the

process, reduce waiting and work-in-process inventory, and use

resources more efficiently.

35

Little’s Law

•

Flow time, or cycle time, is the average time it takes to

complete one cycle of a process.

•

Little’s Law is a simple formula that explains the

relationship among flow time (T ), throughput (R ), and

work-in-process (WIP ).

Work-In-Process = Throughput × Flow Time

or

WIP = R × T

[7.3]

•

If we know any two of the three variables, we can compute the third.

36

Solved Problem

Suppose that a voting facility processes an average of

50 people per hour and that, on average, it takes 10

minutes. What is the average number of voters in the

process? for each person to complete the v

Solution

WIP = R T

= 50 voters/hr (10 minutes/60 minutes per hour)

= 8.33 voters

37

Solved Problem

Suppose that the loan department of a bank takes an

average of 6 days (0.2 months) to process an

application and that an internal audit found that about

100 applications are in various stages of processing at

any one time. Using Little’s Law, we see that T = 0.2

and WIP = 100. What is the throughput? the v

Solution

R = WIP/T = 100 applications/0.2 months

= 500 applications per month

38

Solved Problem

Suppose that a restaurant makes 400 pizzas per week,

each of which uses one-half pound of dough, and that

it typically maintains an inventory of 70 pounds of

dough. In this case, R = 200 pounds per week of

dough and WIP = 70 pounds. What is the average flow

time?

Solution

T = WIP/R = 70/200

= 0.35 weeks, or about 21/2 days.

39