class Dec. 4

advertisement

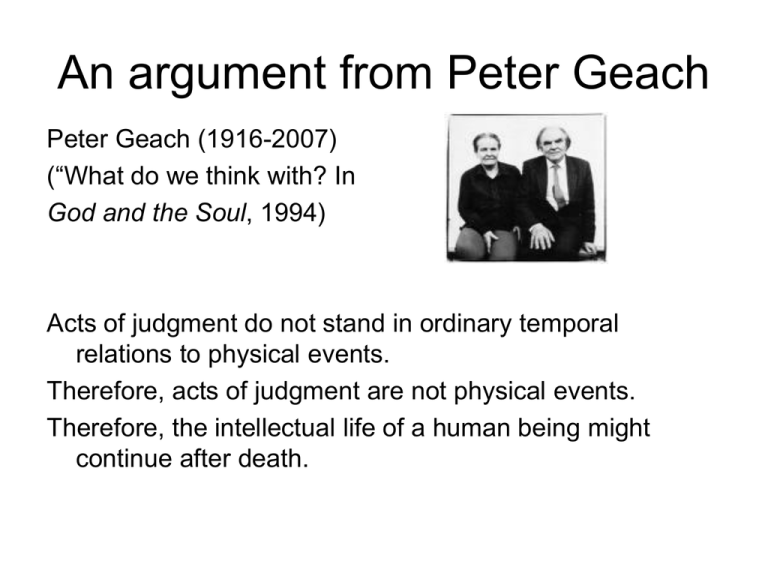

An argument from Peter Geach Peter Geach (1916-2007) (“What do we think with? In God and the Soul, 1994) Acts of judgment do not stand in ordinary temporal relations to physical events. Therefore, acts of judgment are not physical events. Therefore, the intellectual life of a human being might continue after death. Geach’s view of life after death Continued disembodied thought might have such connection with the thoughts I have as a living man as to constitute my survival as a ‘separated soul’. To be sure, such survival must sound a meagre and unsatisfying thing; particularly if it is the case, as I should add, that there is no question of sensations and warm human feelings and mental images existing apart from a living organism. But I am of the mind of Aquinas about the survival of ‘separated souls’, when he says in his commentary on I Corinthians that my soul is not I, and if only my soul is saved then I am not saved, nor is any man. Even if Christians believe that there are ‘separated souls’, the Christian hope is the glorious resurrection of the body, not the survival of a ‘separated soul’(“What Do We Think With?” p. 40). Descartes and Aquinas: Two views of mind and body Descartes Aquinas Mind and body are distinct substances. All conscious states and acts are in the mind. The body is merely a collection of parts of matter. Mind is intellect and will, which are powers of a human being. Acts of intellect and will are not material processes. The soul (principle of life) can exist apart from matter, but only in an incomplete and unnatural state. Descartes’ two arguments for mindbody dualism (1) Methodic doubt shows that a human mind does not have to be extended in order to exist. On the other hand, a body (material thing) does not have to include thinking (consciousness) in order to exist. Therefore, mind and body are two distinct things. (2) A human mind is simple; it has no parts. Every body (material thing) has parts. Therefore a human mind and a human body are two distinct things. Descartes’ First Argument I ask [my readers] to reflect on their own mind, and all its attributes. They will find that they cannot be in doubt about these, even though they suppose that everything they have ever acquired from their senses is false. They should continue with this reflection until they have got into the habit of perceiving the mind clearly and distinctly and of believing that it can be known more easily than any corporeal thing. . . . God can bring about whatever we clearly perceive in a way exactly corresponding to our perception of it. . . . But we clearly perceive the mind, that is, a thinking substance, apart from the body, that is, apart from extended substance. And conversely we can clearly perceive the body apart from the mind (as everyone readily admits). Therefore the mind can, at least through the power of God, exist without the body, and similarly the body can exist without the mind (Second Set of Replies, CSMK, Vol. 2, p. 115,119). Descartes’ Second Argument There is a great difference between the mind and the body, inasmuch as the body is by its very nature always divisible, while the mind is utterly indivisible. For when I consider the mind, or myself in so far as I am merely a thinking thing, I am unable to distinguish any parts within myself; I understand myself to be something quite single and complete. Although the whole mind seems to be united to the whole body, I recognize that if a foot or arm or any other part o the body is cut off, nothing has thereby been taken away from the mind . . . By contrast, there is no corporeal or extended thing that I can think of which in my thought I cannot easily divide into parts; and this very fact makes me understand that it is divisible. This one argument would be enough to show me that the mind is completely different from the body, even if I did not already know as much from other considerations (Meditations, CSMK, Vol. 2, p. 59). An Objection to Descartes' First Argument Even if I can be certain that I exist while being in doubt whether I have a given property, that does not show that I could exist without that property. For example, even if I can be certain that I exist while being in doubt whether I am created by God, does not show that I could exist without being created by God. An Objection to Descartes’ Second Argument A thing can be divisible in one way and not divisible (simple) in another way. For example the word ‘if’ is both divisible (into letters) and not divisible (into words). So even if the mind is not divisible into mental parts, it does not follow that the mind cannot be divided into material parts.