What is Philosophy

advertisement

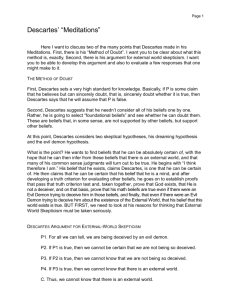

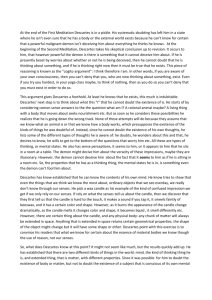

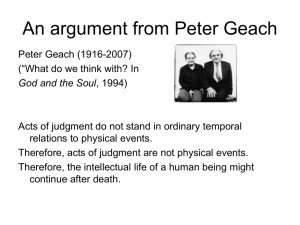

Chapter 1: Knowledge We saw in the introduction that philosophical inquiry is the result of our ability to reflect on ourselves and pose questions about the relation between ourselves and the world. One of the things that triggers such reflection is error. When we make mistakes, we can learn to fix those mistakes, or at least avoid them in the future, by asking: What did I do wrong? This question is inherently an act of self reflection. It requires you to think about yourself, as well as what you were thinking and why. Consider an example: You meet someone named Liza who seems to like you a lot and who is also very charming and cool. You start hanging out together, go to a few parties, and within a few weeks you are thinking about becoming roommates. One day Liza borrows your car, goes joyriding with people you don’t even know, and ends up totaling it. She has no insurance, makes no attempt to compensate you in any way, and from that day on goes around telling everyone what a bitch you are. An experience like that would really shake you up. Among other things it will make you ask: How could I have been such a fool? Why wasn’t I able to see Liza for the kind of person she obviously is? If you are a normal sort of person you will figure out a way to learn something from that experience. You may learn not to be so easily flattered, or to put so much stock in superficial characteristics, or to trust people who you have not known very long or who have never done anything to earn that trust. You might also pose a question like this: What can I do to be absolutely certain that no one ever takes advantage of me like that again? Now, as you probably realize, this is a foolish over reaction. For the only way to make absolutely certain that no one will ever take advantage of you again is to be sure that you never have anything to do with anyone who could possibly do you any harm. In other words you would need to withdraw from society completely, and reject even those who have been close to you all your life, since there is really no telling for sure when they will turn on you. The point of this example is that error can lead us to reflect constructively or destructively. Constructive self-reflection can help us learn from experience. Destructive self-reflection can makes us paranoid. Descartes’ “If you would be a real seeker after truth, it is necessary that at least once in your life you doubt, as far as possible, all things.” Descartes lived during the infancy of modern science. Copernicus, Kepler, Galileo (and Newton soon) had pioneered a way of inquiring into the world that was producing amazing results. But it was a way that brought a huge amount of anxiety from a traditional point of view. The sources of this anxiety were: (1) The method was entirely mechanistic. (2) The method was largely based on probabilities, and could never promise complete certainty. Descartes was a mathematician, and the mathematics with which he was most intimately acquainted did not in any way satisfy itself with mechanism or probabilities. Mathematics, for Descartes was a way of seeing into the very soul of the universe, and it’s results were absolutely certain. The model of inquiry being developed by the physicists and astronomers could promise none of this. A less flattering way of thinking about this is to realize that from a pure philosophical, logical, mathematical point of view physical science is just grubby. You actually have to touch things. That’s just not how we come to know. We come to know by thought, pure thought, and thought alone. The Meditations The Evil Demon and the method of doubt Cogito Ergo Sum and the primacy of the mind. Senses vs. Intellect Blackburn’s Critique Examination of method of doubt o Reconstruction of the argument p22-23 I have been deceived in the past, therefore it is possible that I have always been deceived. o Is the argument coherent? p23-24 If you know that you have been deceived in the past, then you can’t always have been deceived. Can Descartes really succeed in doubting as much as he wants to? What sort of ‘I’ am I? o Mental vs. physical p30 The Cogito establish existence of a mental I, not a physical one. o Is the existence of a thinking thing demonstrated or merely assumed? Lichtenberg claims that Descartes merely assumes his existence as a thinking thing, but is not entitled to it by his method. He’s only entitled to the premise: Thinking is occurring. Clarity and Distinctness o Descartes’ Mathematical Model of Clarity o A + A +B + B = 180 2A + 2B = 180 2(A + B) = 180 A + B = 180/2= 90 o Can we be deceived about our clear and distinct ideas? Yes, both our sensory and our intellectual CD ideas can be wrong. The Trademark Argument (p.34) o This is Descartes proof of God’s existence, which he requires to demonstrate that something exists besides Descartes. The Cartesian Circle (p. 37) o This is a criticism of the reasoning the Trademark argument is involved in. 1. My belief in God’s existence is based only on CD ideas. 2. Beliefs based only on CD ideas always lead to true beliefs. Therefore my belief that God exists is true. Both of these premises can be questioned, but the Cartesian Circle is based on asking for Descartes’ argument for premise 2. Foundations and Webs Hume’s Critique You can’t doubt the principles and beliefs you use to establish doubts. So Descartes project of universal isn’t possible. Rational Foundationalism and Rationalism Rationalism is the theory of knowledge that says all knowledge must be based on a foundation of reason. The ultimate problem with rationalism is that if you start with truths of reason, you never get out to the external world. This is the problem of solipsism. Natural Foundationalism and Empiricism Empiricism is the theory of knowledge that say that all knowledge must be based on a foundation of experience. We build our knowledge on a foundation of what we get from nature. This is a practical starting place, not essentially a logical one. Anti-Foundationalism (p.44) The AF believes that there are no foundational beliefs, and that we can only inspect and repair our system of beliefs, from within. (Remember the Otto Metaphor.) Skepticism (p. 48) Universal skepticism is doubt that we know anything at all. Specifically, the universal skeptic doubts that our beliefs reflect the way the world really is. One useful way of thinking about the significance of Descartes’ meditations is this: Descartes showed us that, while it is possible that the universal skeptic is right, this does not imply, or even suggest that universal skepticism is one of the reasonable alternatives. Descartes moved us from a time when rational belief was connected to the need for certainty, to a time when we recognize that rational belief is possible even under conditions of uncertainty.