PHIL 101 INSTRUCTOR: WILBURN Model answers to publishers

advertisement

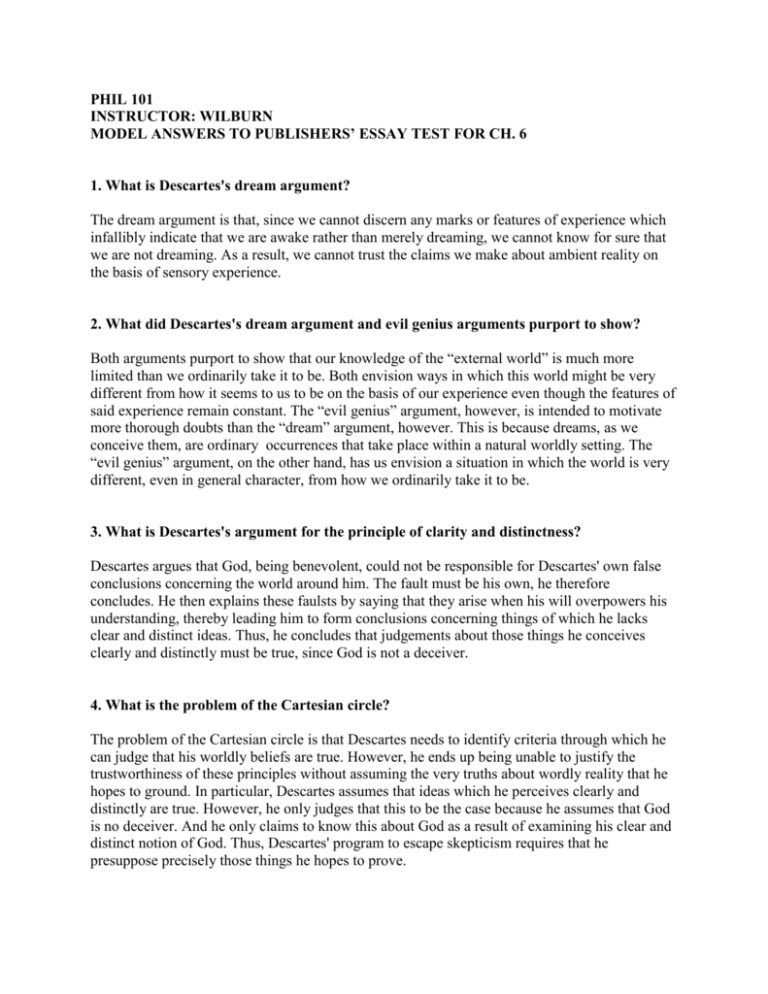

PHIL 101 INSTRUCTOR: WILBURN MODEL ANSWERS TO PUBLISHERS’ ESSAY TEST FOR CH. 6 1. What is Descartes's dream argument? The dream argument is that, since we cannot discern any marks or features of experience which infallibly indicate that we are awake rather than merely dreaming, we cannot know for sure that we are not dreaming. As a result, we cannot trust the claims we make about ambient reality on the basis of sensory experience. 2. What did Descartes's dream argument and evil genius arguments purport to show? Both arguments purport to show that our knowledge of the “external world” is much more limited than we ordinarily take it to be. Both envision ways in which this world might be very different from how it seems to us to be on the basis of our experience even though the features of said experience remain constant. The “evil genius” argument, however, is intended to motivate more thorough doubts than the “dream” argument, however. This is because dreams, as we conceive them, are ordinary occurrences that take place within a natural worldly setting. The “evil genius” argument, on the other hand, has us envision a situation in which the world is very different, even in general character, from how we ordinarily take it to be. 3. What is Descartes's argument for the principle of clarity and distinctness? Descartes argues that God, being benevolent, could not be responsible for Descartes' own false conclusions concerning the world around him. The fault must be his own, he therefore concludes. He then explains these faulsts by saying that they arise when his will overpowers his understanding, thereby leading him to form conclusions concerning things of which he lacks clear and distinct ideas. Thus, he concludes that judgements about those things he conceives clearly and distinctly must be true, since God is not a deceiver. 4. What is the problem of the Cartesian circle? The problem of the Cartesian circle is that Descartes needs to identify criteria through which he can judge that his worldly beliefs are true. However, he ends up being unable to justify the trustworthiness of these principles without assuming the very truths about wordly reality that he hopes to ground. In particular, Descartes assumes that ideas which he perceives clearly and distinctly are true. However, he only judges that this to be the case because he assumes that God is no deceiver. And he only claims to know this about God as a result of examining his clear and distinct notion of God. Thus, Descartes' program to escape skepticism requires that he presuppose precisely those things he hopes to prove. 5. Does knowledge require certainty? Why or why not? This is a controversial question. But one might argue that knowledge requires, not that we be able to rule out all possible doubt, but that we merely be able to rule out all reasonable doubt. If this is the case, then Cartesian demands for certainty may be misplaced. 6. What is the difference between primary and secondary qualities? Secondary qualities (e.g., color, taste, smell) exist only in perceivers' minds. Primary qualities exist as intrinsic characteristics of external physical bodies (e.g., solidity, mass, or “color” when understood as the reflectance features of external objects that cause perceivers to have such and such visual experiences). 7. How does Locke solve the problem of the external world? On Locke's account, some sensory experiences (i.e., those corresponding to primary qualities, for instance, shape) resemble the primary qualities of perceived objects. Thus, according to Locke, our sensory experiences can and do give us some knowledge of the external world. 8. How would Berkeley respond to the question, If a tree falls in the forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound? Strictly speaking, it doesn't. Certainly, sound waves are ommitted, but no auditory experiences exist, since no auditory sense organs exist as causal conduits through which they might be created. 9. How does phenomenalism close the gap between appearance and reality? According to phenomenalism, all talk about physical objects is ultimately translatable into talk about experiences. Thus, in talking about the former. One is really talking about the latter. 10. Explain the confusion involved in Berkeley's assertion that it's impossible for something to exist unconceived. This assertion is true only if it taken to mean that one cannot conceive of an object without conceiving it. It is false, however, if it is taken to mean that one cannot contemplate the proposition that a certain object does not, in fact, exist. 11-15. Here there is a weird typo. Questions 1-5 are just repeated. See answers above. 16. Explain the causal theory of knowledge. According to the causal theory, knowledge is not a function of internally accessible justification. Rather, what makes a claim true is the very same thing that causes a person believe it is true. Thus, on this account, knowledge is simply suitably caused true belief. For example, I know that there is an apple in front of me if the presence of an apple before me is the thing that causes me to believe that there is an apple before me. 32. Explain why the defeasibility theory of knowledge cannot be correct. The defeasibility theory is the theory that knowledge is undefeated justified true belief. The reason it allegedly cannot be correct is that there are cases in which an item of defeated, justified true belief can still be an item of knowledge because the defeaters in question are themselves defeated in turn (as in the demented Mrs. Grabbit thought experiment). 18. Explain the explanationist theory of knowledge. The explanationist theory says that x knows that p iff the fact that p itself provides the best explanation available for the existence or x’s evidence for believing that p. 19. Explain how the explanationist theory can handle Gettier-type thought experiments. Consider the two Gettier examples: In the first case, Smith’s belief that the man who will get the job has ten coins in his pocket is not best explained by this fact itself, but rather by his other misleading and defeasible evidence (i.e., he heard that Jones will get the job and knows that Jones has ten coins in his pocket). In the second case, the fact that either Jones owns a Ford or Brown is in Barcelona does nothing to explain why Smith believes this to be the case. This disjunctive fact obtains because Brown is in Barcelona. However, the occurrence of his belief is better explained by Smith’s other misleading and defeasible evidence (i.e., his evidence for thinking that Jones owns a Ford). 20. Is the explanationist theory an internal theory of knowledge? Why or why not? The authors take the explanationist theory, as described in (33), to be identical to the following: x knows that p iff (1) x believes that p, (2) p is true, (3) x is justified in her belief that p, (4) when the totality of evidence has been taken into consideration, p is left undefeated. Because this account involves justification, it is internalistic. In causal theories, the fact known causes the knowers belief. But in explanationist theories, the fact known best explains the knower’s evidence for his belief.