Notes on Descartes` External World Skepticism

advertisement

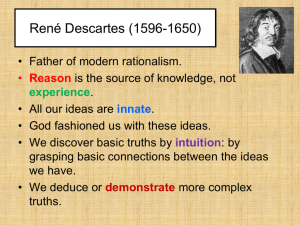

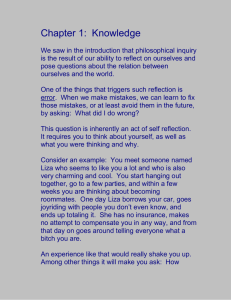

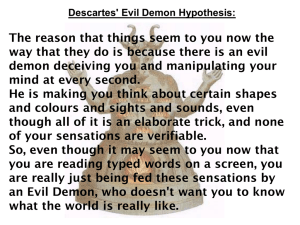

Page 1 Descartesʼ “Meditations” Here I want to discuss two of the many points that Descartes made in his Meditations. First, there is his “Method of Doubt”. I want you to be clear about what this method is, exactly. Second, there is his argument for external world skepticism. I want you to be able to develop this argument and also to evaluate a few responses that one might make to it. THE METHOD OF DOUBT First, Descartes sets a very high standard for knowledge. Basically, if P is some claim that he believes but can sincerely doubt, that is, sincerely doubt whether it is true, then Descartes says that he will assume that P is false. Second, Descartes suggests that he neednʼt consider all of his beliefs one by one. Rather, he is going to select “foundational beliefs” and see whether he can doubt them. These are beliefs that, in some sense, are not supported by other beliefs, but support other beliefs. At this point, Descartes considers two skeptical hypotheses, his dreaming hypothesis and the evil demon hypothesis. What is the point? He wants to find beliefs that he can be absolutely certain of, with the hope that he can then infer from these beliefs that there is an external world, and that many of his common sense judgments will turn out to be true. He begins with “I think therefore I am.” His belief that he exists, claims Descartes, is one that he can be certain of. He then claims that he can be certain that his belief that he is a mind, and after developing a truth criterion for evaluating other beliefs, he goes on to establish proofs that pass that truth criterion test and, taken together, prove that God exists, that He is not a deceiver, and on that basis, prove that his math beliefs are true even if there were an Evil Demon trying to deceive him in those beliefs, and finally, that even if there were an Evil Demon trying to deceive him about the existence of the External World, that his belief that this world exists is true. BUT FIRST, we need to look at his reasons for thinking that External World Skepticism must be taken seriously. DESCARTES ARGUMENT FOR EXTERNAL-W ORLD SKEPTICISM P1. For all we can tell, we are being deceived by an evil demon. P2. If P1 is true, then we cannot be certain that we are not being so deceived. P3. If P2 is true, then we cannot know that we are not being so deceived. P4. If P3 is true, then we cannot know that there is an external world. C. Thus, we cannot know that there is an external world. Page 2 This is really a fascinating argument. The premises seem to be true, but the conclusion seems absolutely insane. How to respond to it? First, there is the “Pragmatist Response.” Basically, the idea is that this argument is sound, and yet, we have practical reasons to believe and act as if there is an external world. For example, itʼs hard to see how we could survive if we didnʼt really believe that if we jumped out of a window, we would fall and actually hit external ground. Notice that this response simply embraces skepticism. Notice also that there is no reason, based on what Descartes says in his Meditations (or anywhere else) that he ever meant to recommend that we not believe in the existence of the External World for purposes of everyday living. Second, there is a “Contextualist Response”. Basically, the idea is that what it takes to know some claim depends upon which standards are relevant. If the standards are high, we donʼt know that there is an external world. If the standards are low, we do. Typically, so this response goes, the standards are low unless we are considering some evil demon hypothesis, and so, typically we know that there is an external world with chairs, tables, and mountains. Notice that this response embraces skepticism too, but tries to quarantine it by claiming that skepticism is true only when we are considering arguments like Descartesʼ argument. Third, there is the “Foundationalist Response” and it comes in two forms. First, the strong form claims that we can know only what we are certain of, or what follows logically from what we are certain of. This form entails skepticism since the existence of an external world does not follow logically from what we are certain of. Second, there a weak form of Foundationalism. This form claims that we can know what we are certain of, or what is made probable by what we are certain of. Here, the idea is that the way things appear to us makes it probable that there is an external world that is causing these appearances. The worry with this second form is that merely being probable seems to be insufficient for knowledge. Suppose that I buy a lottery ticket. I know, for example, that it will likely lose and it is extremely probable that it will lose. Nonetheless, I donʼt know that it will lose. So, these responses to Descartes argument all have serious problems. Are there any others?