二、笛卡尔,霍布斯与剑桥的柏拉图主义者 - Zhongwei Li Philosophy

advertisement

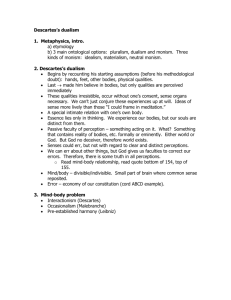

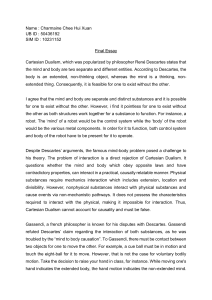

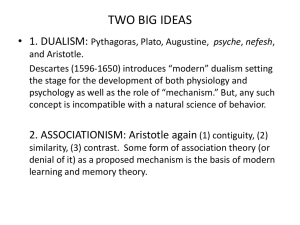

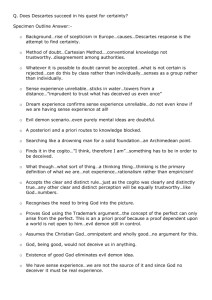

笛卡尔、霍布斯与剑桥柏 拉图主义者 李忠伟 Zhongweili.net 笛卡尔(Descartes,1596-1650): 我思故我在 Descartes’ Life and Work Born 31 March 1596,France Died 11 February 1650 (aged 54) Stockholm, Sweden Main interests: Metaphysics, Epistemology, Mathematics Notable ideas: Cogito ergo sum, method of doubt, Cartesian coordinate system, Cartesian dualism, ontological argument for the existence of Christian God It seems to me that men's thoughts freeze here during winter, just as does the water. 生平 1. 生平介绍 2. As soon as my age allowed me to pass from under the control of my instructors, I entirely abandoned the study of letters, and resolved not to seek after any science but what might be found within myself or in the great book of the world. . . .I spent nine years in roaming about the world, aiming to be a spectator rather than an actor in all the comedies of life. while I do not lack any conveniences of the most frequented cities, I have been able to live a life as solitary and retired as though I were in the most remote deserts. (AT VI. 2, 9, 31; CSMK I.111, 115, 126) 两部重要哲学著作: 《谈谈方法》和《第一哲学沉思录》 笛卡尔的早期科学与哲学工作 笛卡尔早年的工作主要集中在数学和物理学(特别是光学) ,发明了坐标系和解析几何。 《世界》的主题: ‘the nature of light, the sun and the fixed stars which emit it; the heavens which transmit it; the planets, the comets and the earth which reflect it; all the terrestrial bodies which are either coloured or transparent or luminous; and Man its spectator’ 笛卡尔的《论方法》及其四条原则 (A Discourse on Method: the right way to use one’s reason and seek truth in the sciences.)(简单、深刻、优雅) 预设:理性是存在的,人们能通过理性之光理解自身与世 界。 思想与寻求真理四原则 1.方法论的怀疑:在不清楚明白知道某件事为真之前,就 绝对不要接受它。换言之,即谨慎地避免卤莽和偏见,并 除了那呈现在我的理性之中既极清晰明了,而又毫无怀疑 余地的事物之外,不作任何其它的判断。 2.分析:要把每一项在审察中的困难,尽问题所许可地划 分成若干部分,好达到充分的解决。 3.循序渐进:要按次序引导我的思想,由最简单和最容易 明了的事物着手,渐渐地和逐步地达到最复杂之事的知识, 甚至在那些本质上原无先后次序的事物,也为假定排列层 次。 4. 周全:在每一种研究上,枚举事实要那么周全,而且审 查要那么普遍,但可确实地知道没有任何遗漏。 笛卡尔式的《第一哲学沉思录》 和方法论怀疑(Methodological Doubt) 怀疑之目的:检验是否存在确定的真理,以作为知识大厦 基础。 系统怀疑的步骤: 怀疑感性知识、怀疑数学知识。 怀疑感性知识 论证1:感性欺骗性论证 I have noticed that the senses are sometimes deceptive; and it is a mark of prudence never to place our complete trust in those who have deceived us even once. 笛卡尔的睡梦论证: Descarts’ Dream Argument 关键引文: 我的沉睡经常使我相信,我在这里,穿着便服,坐在火 炉边——而实际上我却没穿衣服躺在床上。每念及此,我 明确地认识到,没有任何明显的标志,可以区分清醒与 睡梦。 But right now my eyes are certainly wide awake when I gaze upon this sheet of paper. This head which I am shaking is not heavy with sleep. I extend this hand consciously and deliberately, and I feel it. Such things would not be so distinct for someone who is asleep. As if I did not recall having been deceived on other occasions even by similar thoughts in my dreams! 睡梦论证的限度 没有证明:数学、逻辑等普遍真理是可疑的。 Arithmetic, geometry, and other such disciplines, which treat of nothing but the simplest and most general things and which are indifferent as to whether these things do or do not in fact exist, contain something certain and indubitable. For whether I am awake or asleep, two plus three make five, and a square does not have more than four sides. 睡梦论证的强化版——邪恶精灵论证 (Evil Genius Argument) 我不知道,邪恶精灵使得(1)没有天地,没有广延的事物,以及 形状,大小,位置等等;同时使得(2)所有这些事情表面上对我 显现得如它们当下显现的那样。 How do I know that Evil Genius did not bring it about that there is no earth at all, no heavens, no extended thing, no shape, no size, no place, and yet bringing it about that all these things appear to me to exist precisely as they do now? 同 理 : 我 们 也 无 从 知 道 , 当 我 在 做数 学 题 的 时候 , 例 如 做 2+3=5的时候,邪恶的精灵没有总是欺骗我。 缸中之脑:邪恶精灵论证的现代版本 Brain in a Vat(BIV): Modern Version of EGA 如果我知道我在太阳下漫步, 那么我就知道我不是BIV 可是并非我知道我不是BIV —————— 我不知道我在太阳下漫步 流行文化中的 “睡梦论证”和“邪恶精灵论证” 《黑客帝国》 《爱丽丝漫游仙境记》 Inception 笛卡尔:我思故我在(Cogito, ergo sum) 尽管我能怀疑感性世界的存在和数学信念的真实性,我们仍然不 能怀疑自我的存在。 我思故我在 I decided to feign that everything that had entered my mind hitherto was no more true than the illusions of dreams. But immediately upon this I noticed that while I was trying to think everything false, it must need be that I, who was thinking this, was something. And observing that this truth ‘I am thinking, therefore I exist’ was so solid and secure that the most extravagant suppositions of sceptics could not overthrow it, I judged that I need not scruple to accept it as the first principle of philosophy that I was seeking. (AT VI. 32; CSMK I.127) 笛卡尔的心物二元论(Dualism) 只有两种彻底不同的实体:物质的本质是其广延;心灵的 本性是其会思考,物质并不属于自我本性。 两种实体相互不同(mutually exclusive):具有不同属性; (B)两种实体构成宇宙(mutually exhaustive)。 理由? 论上帝存在及其作为外部知识的保证 关于上帝存在的论证:自我存在;我有一个全善、全能、 无限的观念;该观念不能是自我产生的,因为自我是有限 的;故而该观念只能来自全知全能全善的上帝。QED。 关于外部知识:上帝是善意的;在我良好使用自身官能、 理性之后所得到的信念应该是真的。 笛卡尔论知识体系及其伦理学 知识体系:知识之树,根为形而上学,树干为物理学,而 树枝为道德和应用科学。 笛卡尔的伦理学:斯多亚学派的。保持最少欲望与心灵平 静的生活。 笛卡尔的知识之树 笛卡尔的遗产(Legacy)和历史地位 其哲学思想以及数学遗产; 对哲学上个人体系创新的信念,开创了新的哲学时代。 笛卡尔是理性主义哲学的开创者; 承接中世纪(如自然之光的思想),开启现代哲学。 笛卡尔的墓志铭 No man is harmed by death, save he Who, known too well by all the world, Has not yet learnt to know himself. 思考问题 1. 简述笛卡尔的几条方法论原则及其应用; 2. 简述笛卡尔对外部世界以及对数学、逻辑知识的几个怀 疑论的论证; 3. 简述笛卡尔对“我思故我在”的论证。 4.简述笛卡尔对上帝存在的论证; 5.简述笛卡尔的“知识之树” 6.简述笛卡尔的历史地位。 霍布斯(Hobbes, 1588—1679) 物质主义的政治哲学家 霍布斯的形而上学:物质主义(Materialism) 与笛卡尔不同,霍布斯只认为一种实体存在,即物质。 霍布斯否认笛卡尔意义上的心灵实体。“incorporeal substance”就跟“round quandrangle”一样。 与笛卡尔相同: 霍布斯认为物质世界由运动、广延得到解释(p.43); 否认诸如颜色、声音、温度等“第二属性”的根本性,只 承认广延与运动这些第一属性。 ‘Whatseover accidents or qualities our senses make us think there be in the world, they are not there, but are seemings and apparitions only. The things that really are in the world without us, are those motions by which these seemings are caused’ (Elements of Law I.10). 霍布斯的政治学说:契约主义 理论起点: 人性理论自然状态(State of Nature)人性本恶,人对人像狼,所 有人对所有人的战争,人类最惧怕无端暴死。 契约论(Contractarianism): 根据一些理性原则,为避免暴死,人类由于关注自身的利益,理 性地推断出,必须让渡部分自由,以换取相互之间的让步。人们 订立契约、确立主权、保证各自利益。 人与人之间订立某种“源初”契约,设定了某种最高主权,其自 由被让渡给某个能够根据法律惩处破坏法律的权力机构。该权力 机构是法律和财产权的来源,是正义与非正义的来源(反对道德 原则内在说),其功能是保证源初契约的执行和其它衍生契约。 霍布斯的语言哲学1:语言的四重功能 (1)记录、描述:First, to register, what by cogitation we find to be the cause of any thing, present or past; and what we find things present or past may produce, or effect: which in sum, is acquiring of arts. (2)传递:Secondly, to show to others that knowledge which we have attained; which is, to counsel and teach one another. (3)以言行事:Thirdly, to make known to others our wills and purposes, that we may have the mutual help of one another. (4)聊以自娱:Fourthly, to please and delight ourselves, and others, by playing with our words, for pleasure or ornament, innocently. (L, 21) 霍布斯的语言哲学2:唯名论(Nominalism) 所有词语都是名字(Names),而名字只指称个体。名字种 类可以分为: Proper Name (Peter) Common Name (Horse) Abstract Name (Red, Length) Descriptions(Circumlocutions)(He that writ the Iliad) 名 字 指 称 个 体 而 非 Universal. Universal names like ‘man’and ‘tree’ do not name any universal thing in the world or any idea in the mind, but name many individuals, ‘there being nothing in the word Universal but Names; for the things named, are every one of them Individual and Singular’. 霍布斯的语言哲学3:基于唯名论的语义学 S is p:“S is p” is true iff S and p names the same S. 为什么“苏格拉底是正义的(Socrates is just)”是真的? 苏格拉底命名苏格拉底; 正义的命名所有正义的东西; 两者都是苏格拉底的名字,那么苏格拉底是正义的。 思考问题: 1.简述霍布斯与笛卡尔形而上学的异同; 2. 简述霍布斯的契约主义政治学说,根据这种学说,如何 批判笛卡尔关于道德准则内在论? 3.根据霍布斯的唯名论(Nominalism),如何理解抽象词的 指称? 4.根据霍布斯的语言哲学,试述为什么“苏格拉底是不死 的”是错误的?试述为什么“人是活着的生物”是正确的? 该理论可能有什么问题? 剑桥的柏拉图主义者 柏拉图与奥古斯丁之友 人物与特点 时期与人物:十七世纪中叶,包括RalphCudworth(16171688),Henry More(1614-87)。 共同点是以柏拉图、普罗蒂诺以及早期教父为思想来源。 宗教倾向和观点:反对清教,反对加尔文派前定论,认同 自由意志,认同宗教自由,但反对将自由扩展到无神论者。 反对物质主义(No Spirit, No God)。 形而上学 1. 认同笛卡尔的二元论,试图论证灵魂不朽与上帝存在。 2. 与笛卡尔和霍布斯不同,他们认为物质世界不能完全用 物质和运动解释;即便是物质也需要某种非物质的原则进 行解释;动物也有感觉。 认识论 大体认同笛卡尔,认为存在内在观念,心灵不是白纸,任 感知图画,而是一本书,感知将其打开。内在观念还包括 内在的道德原则(Cudworth认为道德并不来自于人类的契 约,而是内在于人类)。 道德与上帝意志 与笛卡尔不同,认为上帝意志并非道德原则来源,故无法改 变内在道德原则。‘Virtue and holiness in creatures are not therefore Good because God loves them, and will have them be accounted such; but rather, God therefore loves them because they are in themselves simply good.’