Power Point Slides for Chapter 3

advertisement

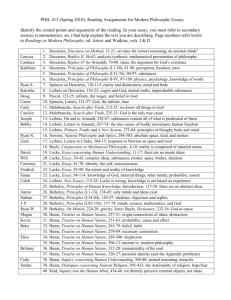

Chapter 3: Psychology During Mid-Millennium Transitions 15th to the end of the 18th Century While there is no universally accepted theory to explain the global complexity of mid-millennium transitions, historians generally agree about Western civilization. They describe this period in terms of three fundamental developments: The Renaissance The scientific revolution The Reformation, Historians associate the Renaissance with the reintroduction of major elements of Greco-Roman antiquity in arts, sciences, and education. As the advancing Reformation movement grew in Europe, religious faith was becoming increasingly a matter of individual conscience. Scientific revolution: For the educated, the mysterious and unpredictable quality of nature was unfolding into something clear and quantifiable. Scientific Discoveries of the 16th and 17th Centuries: Selected Examples • In 1543, Nicolas Copernicus theorized that the Earth rotated around the sun. • In 1621, Johannes Kepler established that the celestial orbits were not circular but elliptical. • In 1638, Galileo Galilei introduced his theory of inertia. • In 1641,William Gilbert published his theory of magnetism. • In 1628,William Harvey collected evidence about blood circulating in the body and in 1651 formulated the main principles of embryology. • In 1687, Newton articulated the laws of motion. • In 1665, Robert Hooke first reported to the world that life’s smallest living units were “little boxes.” These were later known as cells. Girolamo Cardano (1501–1576) wrote a detailed autobiography (a relatively common practice among scientists), filled with meticulous details about his activities and psychological experiences including thought process, doubts, and anxieties. He provided an interesting account of therapeutic techniques, such as self-inflicted physical pain to reduce more serious psychological disturbances. Small pain or irritation, he believed, would overtake psychological anguish caused by a more serious disturbance. Anatomy of Melancholy By Robert Burton published in 1621 was one of the earliest books devoted to anxiety and mood problems Mysticism, a belief in the existence of realities beyond perceptual reflection or scientific explanations but accessible by subjective experience, remained a very important element in the lives of the Christian and Jewish communities in Europe and in the Muslim communities of the Middle East and North Africa. Witchcraft was part of human folk tradition supported by religious beliefs. From the evidence accumulated in printed sources, including The Malleus Maleficarum, we can infer that the “work of the devil”, and witchcraft in particular, was attributed to psychological and behavioral symptoms such as delusions, hallucinations, or manic episodes. René Descartes (1596–1650) Descartes believed that animal spirits are light and roaming fluids circulating rapidly around the nervous system between the brain and the muscles. The Body Animal spirits come into contact with the brain and trigger, strengthen, or weaken affective states in the soul, or passions of the soul. The Brain Descartes distinguished six basic passions: wonder (surprise), love, hatred, desire, joy, and sadness. Passions of the Soul R E F L E X E S Benedict Spinoza (1632–1677) His views of emotions We too often follow our impulses and become virtual slaves to our wishes We lose freedom because we are trapped in the continual search for gratification of our wishes without knowing why we do so To avoid this endless quest for pleasure, we should know more about the causes of our own actions Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716) According to Leibniz, the soul has an infinite number of monads and therefore perceptions. Monads can perceive, and the soul possesses “little perceptions” that are not conscious but could become so because of memory and attention. The soul possesses several areas of knowledge distinguished by the strength of apperception: clear knowledge, fragmented knowledge, and unconscious knowledge. Leibniz is one of the first scholars to have identified a category of unconscious psychological phenomena. Like Descartes, Leibniz believed in the existence of innate ideas because he felt it was impossible to derive certain abstract ideas directly from experience. Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) Hobbes believed that the essence of human behavior is in physical motion and that the principles of Galileo’s mechanics could explain sensation, emotions, motivation, and even moral values. Hobbes understood the soul as mechanical movements in the body. He laid foundations for the empirical branch of epistemology and psychology and supported empiricism, the scientific belief that experience, especially sensory processes, is the main source of knowledge. John Locke (1632–1704) Locke believed that the child’s mind is a “clean board,” or in Latin, tabula rasa. Experiences can be recorded in the mind in a fashion similar to the way in which teachers use a piece of chalk to write on the board. Following a tradition in epistemology, Locke continued to distinguish between the primary and secondary qualities of things. Primary qualities are inseparable from the body and reflect the qualities of objects; these included extension, motion, number, or firmness. Secondary qualities, such as color or taste, exist only in sensations. George Berkeley (1685–1753) Perception To understand Berkeley is to comprehend his famous principle: to exist is to be perceived (esse est percipi in Latin). We always use our sensations to prove the desk’s existence! Therefore, every object requires a perceiving mind. David Hume (1711–1776) Hume contributed to psychology by developing pragmatic views in the fields of naturalism and instrumentalism. Naturalism refers to the view that observable events should be explained only by natural causes without assuming the existence of divine, paranormal, or supernatural causes such as “magic” or “evil eye.” Instrumentalism applied to Hume’s works means that human action is reasonable as long as it justifies this individual’s goals. David Hume (1711–1776) Hume’s Views of Personality. 1. The Epicurean displays elegance and seeks pleasure. 2. The Stoic is a person of action and virtue. 3. The Platonist is the person of contemplation and philosophical devotion. 4. The Skeptic is the person of critical thinking. Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) “Golden Rule”: act according to your rational will but assume that your action, to be considered moral, should become a universal law for others to follow. He believed that such a moral imperative should be innate, which means, in contemporary terms, that all human beings should have a natural predisposition for moral behavior. Many years later, founders and supporters of humanistic psychology and its many branches emphasize the moral side of human behavior and, like Kant, they celebrate moral act as a natural expression. Paul-Henri Thiry (1723–1789) He believed that the brain is capable of producing within itself a great variety of physical motion called intellectual faculties. In his materialist outlook, the brain is the center of all activities attributed to the soul. To understand how the brain works, scientists should combine their efforts as physicians, natural philosophers, and anatomists. In addition to his publications, he was best known for hosting his famous salon -- a common name for periodic “gettogethers” of people of social status and intellectual merit. Abbé de Condillac (1714–1780) Acquisition of knowledge, according to Condillac Julien Offray de LaMettrie (1709–1751) In “Man a Machine”, he defended a view that a human being is just a complex machine. Each tiny fiber or part of a living body moves by a particular principle. People are trained to perform simple and complex tasks in the same way that animals are trained to look for food and protect themselves. A geometrician, according to La Mettrie, learns to perform the most complicated calculations in the same way as a trained animal learns to perform tricks. Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778) He openly glorified the very early stages of human civilization, the view endorsed today by some cultural anthropologists and psychologists (Shiraev & Levy, 2009). Rousseau even coined the term, “noble savage” suggesting that people were essentially good when they lived under the rules of nature, before modern civilizations were created. Those rules, in his mind, stood for honesty, reliability, and spiritual freedom.