Powerpoint

advertisement

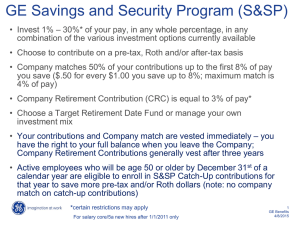

The Shift from DB to DC: Economic Impact on Plan Members Presentation to: Workplace Pensions: Next Generation or Final Frontier Centre for Law in the Contemporary Workplace, Queen’s Law School Toronto, May 2014 Bob Baldwin Cautions • Terms DB and DC lack precise meanings • Heterogeneity within each of DB and DC • DB and DC data may reflect characteristics other than inherent differences • EG: size, differences in governance and management, level of earnings (RPP needs) • Data not perfectly fit for purpose • Relevance will trump reliability Extent of the Shift from DB to DC: PPIC Data All 1980 1990 1999 2012 DB 94% 91% 85% 73% DC 5% 8% 13% 16% Private Sector 1980 1990 1999 2012 DB 90% 85% 77% 51% DC 8% 13% 20% 29% Note too: • In 2012, 488,000 members in plans transitioning from DB to DC (compared to 1 m in DC plans) • PPIC source picks up registered RPPs but not group RRSPs • In 2011, 3m participate in group RRSPs (3 x the number in registered DC) • Migration from small registered DC to group RRSP • Growth in small DB in the private sector Retirement Wealth • Participation in an employment pension matters (SFS, 2012) • Among households aged 55 to 64, 77% have private pension assets with a median value of $304K • 69% have RRSPs with a median value of $50K • Will aim for SFS data on DB vs DC wealth • MVA per member in DB and DC plans (PPIC) • In 2012, the average MVA/member in DB plans was $252K vs $50K for DC plans • DB plan members more likely to identify their workplace pension as their primary source of retirement income • 64% vs 47% (Survey of Financial Preparedness, 2009) An Accounting Identity • Contributions + investment returns = benefits + expenses • Underlines a conceptual point and helps organize information • Where do investment and other uncertainties show up in DB and DC • Pure DB: all on the contribution rate • Pure DC: all on the benefits • A reformulation: In DB the rate of saving is adjusted regularly to meet the benefit obligations; in DC the benefit is adjusted to reflect the contributions and investment returns DB vs DC: The General Picture • Lower level of contributions in DC • Dollar amounts of contributions per member higher in DB than in registered DC ($9K vs $3.8K, 2010) – normalized rate data would be preferred • Actuarial firm identifies 8% as typical DC contribution rate • Life industry spokesperson: employer GRRSP contributions 4% • Marginally lower investment returns in DC • Evidence is from US, sample bias (DC all 100 + members) • Slight advantage to DB but not consistent from year to year (TW study: 0.76 bps over 17 yrs through 2011; 0.39 in last 5 yrs – net of estimated costs) • Well documented problems in US 401K investments • But vs a DC counterfactual, in DB group and individual returns can diverge • Higher fund management and admin expenses in DC • Jog to F/P/T ministers on fund management fees: Private DB 30-45 bps; Public DB 25-35 bps; corp DC 60 bps; corp RRSP 92 bps; retail 40 for ETF/index and 200 on average for active with advice. • Other sources provide a mixed picture • Large size (to a point) and capacity for in-house fund management are clearest determinants of cost The Predictability Problem with DC • DC outcomes depend heavily on conditions in financial markets around retirement age • Purchases of deferred annuities and life cycle investing can limit the impact – at a price • MS modelling • DC replacement rates vary from a high of 48% (2,000) to 14% (1977): investment volatility and salary growth • Blake modelling: 2 scenarios • Scenario 1: DC portfolio and DB are identical M result, DC = 100% of DB, 23% chance DC>DB and 44% chance of DC < 25% DB • Scenario 2 (life cycle): DC portfolio shifts to low risk assets 5 years before retirement M result, DC = 72 % of DB result, only 7% chance of DC < 25% of DB; only 11% chance of DC > DB • NB: mirror image in DB • Variable contributions (consumption opportunities foregone) • Amplitude of variation may be smaller in DB (amortization periods, smoothing of values, etc) Comfort: An Additional Consideration • No need to worry about • Investment decisions (low priced access to expertise) • Longevity risk • Converting assets from accumulation to decumulation • But DC is entrenched • Can be organized to reduce discomfort Outcomes with No Change to DC • Impacts greatest for people earning above half AWS • Greatest need for RPP income to meet earnings replacement goals • Impacts on retirement income and retirement age • Less certainty about amounts of income and retirement age • Likely lower income and later retirement • Some attenuation thanks to interactions with other components of the RIS, income tested benefits and progressive PIT • Impacts more clear on gross versus net replacement rates • DB entails variable foregone consumption opportunities prior to retirement Final Reflections 1 • Future context may be difficult for DB and DC • Ratio of the retirement period to the period of working life • Gap between returns on financial assets and salary growth • But, tighter labour market context may make DB pensions more interesting for employers • retention, orderly exit, and mid career recruitment will become more important • Pension design is not a binary choice between DB and DC • Need to explore designs that involve elements of DB and DC – especially in the private sector • Predictability of contributions and benefits are both desired Final Reflections 2 • Single firms are not appropriate organizational platforms for pensions • Too small, lack expertise, and conflicts • Even with CPP expansion or ORPP, it is important to get workplace pensions right • Next generation or final frontier • Next generation: pensions as we know them are young; we are learning how they function in different environments