chapter9.2013 - WordPress.com

advertisement

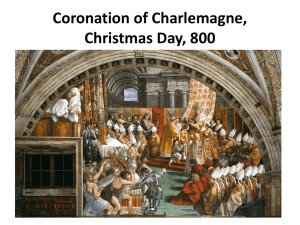

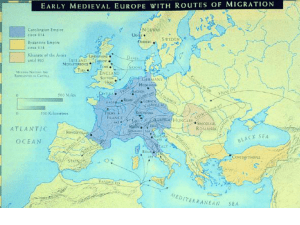

Chapter Nine: The Rise of Medieval Culture Culture and Values, 8th. Ed. Cunningham and Reich and FichnerRathus 400 ce – 800 ce Monasteries are founded Warring tribes migrate throughout Europe following the collapse of the Roman Empire Venerable Bede writes the Ecclesiastical History of the English People The Old English epic Beowulf is created Charlemagne battles the Spanish emirate without conclusive Results; events gives rise to The Song of Roland 800 ce – 1200 ce The feudal system becomes the dominant social structure throughout Europe Charlemagne, a Frank, is crowned emperor of the new Holy Roman Empire Charlemagne supports learning, monasteries, and the writing of books The Ottonian period begins following the death of Charlemagne William I (William the Conqueror) invades England and becomes England’s first Norman king The Romanesque style of architecture dominates European cathedral construction Charlemagne: Ruler and Diplomat (742-814) Papal Coronation – Leo III, Christmas 800 – Revival of Western Roman Empire Feudal Administration – Legal decrees – Bureaucratic system – Literacy Foreign Relations – Byzantines, Muslims Charlemagne: Economic Developments Stabilized the currency – Denier Trade Fairs Tolerance of Jews Jewish merchants and the Near East Trade Routes Import / Export Relationships – Iron Broadswords Learning in the Time of Charlemagne “Palace School” at Aachen Scholar-teachers Curriculum – Trivium, quadrivium – Mastery of texts Text reform – Literary revival = Liturgical revival Literacy as prerequisite for worship Learning in the Time of Charlemagne Alcuin of York – Corrected errors in the Vulgate Bible – Developed Frankish school system Literacy and Women – Aristocratic women – Dhouda- not a nun but wrote a text on Christian living – Illuminated manuscripts Benedictine Monasticism Early monasticism – Varying monastic lifestyles – No predominate rule The Rule of St. Benedict “Magna Carta of monasticism” – Poverty, stability, obedience, chastity – Balance of prayer, work, and study – Horarium – Horarium Monasticum 2:00 A.M. Rise 2:10–3:30 Nocturns (later called Matins; the longest office of the day) 3:30–5:00 Private reading and study 5:00–5:45 Lauds (the second office; also called “morning prayer”) 5:45–8:15 Private reading and Prime (the first of the short offices of the day); at times, there was communal Mass at this time and, in some places, a light breakfast, depending on the season 8:15–2:30 Work punctuated by short offices of Tierce, Sext, and None(literally the third, sixth, and ninth hours) 2:30–3:15 Dinner 3:15–4:15 Reading and private religious exercises 4:15–4:45 Vespers—break—Compline(night prayers) 5:15–6:00 To bed for the night Women and the Monastic Life Scholastica (d. 543) – St. Benedict’s sister Brigit of Ireland (d. 525) Hilda, abbess of Whitby (614-680) Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179) Monasticism and Gregorian Chant Development of sacred music – Gregorian Chant – Ambrosian music – Mozarabic chant – Frankish chant Monasticism and Gregorian Chant Gregorian chant and Carolingian reform Gregorian characteristics – – – – – Monophonic- one or many voices singing one single melodic line Melisma-extensive addition of a chain of intricate notes sung on the vowel sound of a single syllable Acapella-vocals no instrumentation Cantus planus-plain song Neums-notations used in Gregorian chant Liturgical Music and the Rise of Drama The Liturgical Trope – Verbal elaborations of textual content – Added to the long melismas – Aid in memorization – Origin of drama in the West Quem Quæritis Medieval Literature Venerable Bede – – Father of English history Ecclesiastical History of the English People Beowulf Hildegard of Bingen http://www.macalester.edu/~warren/courses/Hildegard/art.html – Writer, painter, illustrator, musician, critic, preacher – Scivias (The Way of Knowledge), Physica (botany), Causae et Curae (illness & cures), Symphonia (hymns & songs), Ordo Virtutum Roswitha -poet, playwright 9.1 Hildegard of Bingen, “Vision of God’s Plan for the Seasons,” from De operatione Dei, 1163-1174 The Morality Play: Everyman Links liturgical and secular drama Allegorical, moralistic – Instructs for moral conversion Religious themes – Life as a pilgrimage – The inevitability of death (memento mori) – Faith vs. Free Will Liturgical overtones The Legend of Charlemagne: Song of Roland Charlemagne canonized 1165 – Reliquaries and commemoratives Epic poem – Charlemagne’s battle with the Basques (778) – Chansons de geste (song of deeds), chansons d’histoire (song of history) Oral tradition, jongleurs (wandering minstrels) Military and religious ideals – 11th c. martial virtues and chivalric code Anti-Muslim bias 9.23 Reliquary of Charlemagne The Visual Arts: The Illuminated Book Carolingian manuscripts on parchment Gospel Book of Charlemagne – Utrecht Psalter – Masterpiece of the Carolingian Renaissance Dagulf Psalter – Roman, Byzantine, Celtic styles Carved ivory book covers Carolingian miniscule 9.9 The four evangelists and their symbols, Palatine School at Aachen, early 9th century. Manuscript illustration from the Gospel Book of Charlemagne 9.10 Drawing for Psalm 150 from the Utrecht Psalter, ca 820-840 9.11 Crucifixion, ca. 860-870, carved ivory panel, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, United Kingdom Carolingian Architecture Charlemagne’s Palace at Aachen Kingdom modeled on ancient Rome Palace – – Chapel – – – Large royal hall, lavishly decorated Joined to chapel by a long gallery Church of San Vitale (Ravenna) as model Altar to the Savior (liturgical services) Chapel to the Virgin (reliquary) Charlemagne’s Throne – “…this most wise Solomon.” Palatine Chapel (palace chapel of Charlemagne), 792–805. Interior of the octagonal rotunda and plan. Aachen Cathedral, Aachen, Germany. The Carolingian Monastery Monastery as “miniature civic center” – Complexity of function and design – Center of life for rural populations Saint Gall plan – Basilica style – Designed to house 120 monks, 170 serfs Plan for an ideal monastery, ca. 820. Saint Gall, Switzerland. Reconstruction based on original plan (44″ across, drawn to scale on vellum) in the Library of the Monastery of Saint Gall, Switzerland. The Romanesque Style Large, “Roman-looking” architecture Influenced by travel, expansion – Pilgrimages Heavy stone arches – Larger, more spacious interiors – Fireproof stone and masonry roofs – Church of Saint Sernin in Toulouse Church of Saint Michael (restored exterior), ca. 1001–1031. Hildesheim, Germany. Adam and Eve Reproached by the Lord, 1015. Panel of bronze doors, 23″ × 43″ (58.4 × 109.2 cm). Dom Museum of Saint Mary’s Cathedral, Hildesheim, Germany. Saint Sernin, ca. 1080–1120. Toulouse, France. Floor plan, Saint Sernin. Toulouse, France. 9.19 Nave, Saint Sernin, ca 1020-1180, Toulouse, France The Romanesque Style Exterior decoration (sculpture) – Lack of interior light – Portal (doorway) – Jamb, capital, trumeau – Tympanum (mandorla, archivolts) Church of Sainte Madeleine at Vézelay 9.20 Cathedral of Sainte-Lazare, west tympanum detail of Last Judgment, ca 1120-1135 “Proclamation to the Shepherds,” folio 8 verso from the Lectionary of Henry II, 1007. Manuscript illumination on vellum, 16¾″ × 12⅝″ (42.5 cm × 32 cm). Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich, Germany. Chapter Nine: Discussion Questions Explain the function of the Song of Roland as both religious and political propaganda during the eleventh and twelfth centuries. What values are extolled within the text that would serve religious and political leaders as they shape their culture? Do we, as a culture, subscribe to these same values today? Why or why not? Why was Charlemagne so interested in developing literacy? Explain his motives and methods for establishing schools and supporting scholars. Describe the role of the liturgical trope in the development of drama in the West. For example, how does one begin with the Quem Quæritis trope and arrive at Everyman? Explain the evolution of the art form.