3.6) Ch. 7 Lecture PowerPoint - History 1101: Western Civilization I

advertisement

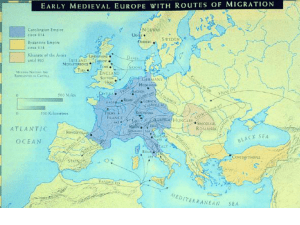

The Struggle to Bring Order The Early Middle Ages, ca. 750-1000 The Struggle to Bring Order The Big Picture Viking Invasions 800-950 Charlemagne’s Kingdom 768-814 700 800 Muslim Assaults 850-950 Magyar Invasions 890- 950 900 Canute’s Unification 1016-1035 1000 2 Bringing Order with Laws and Leadership Struggle for Order – Fragile New Kingdoms: After the disruptions of the fifth, sixth, and seventh centuries, Western Europeans struggled restore order to their societies, and did so by trying to join all members of societies—from nobles to peasants—through ties of law and loyalty. – Emergence of Organized Social Structures: European society was being increasing defined by contractual and personal relationships such as the localized one that existed between peasants and nobles. Kings and the Church were more distant authorities, but their power was growing. 3 Bringing Order with Laws and Leadership The Rule of Law – Germanic Law: Germanic tribes had developed their own rule of law well before they came under Roman influence, but they had had not written it down. – Features of Germanic Legal System: Someone accused of a crime could have character witnesses—twelve honorable men—who would testify in a process called compurgation. Another legal process was called ordeal, which subjected the accused to a form of torture: being forced to pick up a red hot poker or be submerged under water. Whether or not they suffered any ill effects would determine whether they were guilty or not, with the belief that supernatural forces were in play. – Wergeld: Cycles of violence were often prevented by the tradition of “man money,” meaning that death and injury could be monetarily compensated. A free peasant’s life was worth about 200 shillings, while a nobleman’s life was worth 1,200. An ear was worth 30 shillings, while a nose, 60. Women in 4 their childbearing years were worth more than postmenopausal women. Bringing Order with Laws and Leadership The Rule of Law – Intricate System of Law: The fines for everything from an insult to a lost toe may seem bizarre to us now, but they nonetheless represent a growing synthesis of Germanic and Roman traditions as they were increasingly written down. – Law as Instrument of Royal Power: By the eighth century, kings and their royal officials inserted themselves between feuding families, using the law codes as a means to assert their authority. They nonetheless never completely brought their subjects’ desire for vengeance under control. Yet wergeld, compurgation, and trial by ordeal became regular features of medieval law, and helped to consolidate the power of these early monarchies. 5 Anglo-Saxon England: Forwarding Learning and Law • Early Medieval England: It was not unified, but consisted of several different kingdoms, the most prominent being Northumbria, Mercia, and Wessex. • Theodore of Tarsus: Pope Vitalian sent this learned man from the Eastern Mediterranean to become the archbishop of Canterbury, who started organizing the church on the Roman model with a hierarchy of bishops and priests, and started to replace the monastery/missionary organization that preceded it. He also established a school at Canterbury and sent other scholar monks to the north of England to found monasteries, including a large one at Wearmouth-Jarrow. Beowulf was likely recorded during this period or monastic scholarship. 6 Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms, ca. 700 7 Anglo-Saxon England: Forwarding Learning and Law The Venerable Bede: Recording Science and History – The Young Bede: A young scholar studying at Jarrow in the 700s mastered all of the texts available to him, and interpreted classical works in a way that made them accessible to his contemporaries, writing in Latin. – Synthesis: Bede drew upon the work of previous scholars, preserving them and expanding upon knowledge from pervious centuries. – The Nature of Things: This scientific work of Bede’s drew upon work by classical scholars, describing the earth as globe and explaining geography, as well as the orbits of the heavens, stars, and planets. It was the most important scientific work of the medieval era. 8 Anglo-Saxon England: Forwarding Learning and Law The Venerable Bede: Recording Science and History – Bede’s History: The full title of Bede’s most famous work was the Ecclesiastical History of the English People. It tells of the history of Anglo-Saxon England up to ca. 731, and plants the seeds of the idea that the English were indeed a cohesive people. It also was the first work of history to distinguish between scholarly knowledge and rumor. It was also the first to use the B.C./A.D. distinction created by Dionysius Exiguus of Theodoric’s court in Italy, which not many people had read (thus the B.C./A.D. distinction is often credited to Bede). – Roman Perspective: The History tells the tale from the perspective of Roman Christian missionaries coming to England, and their slow conversion of Anglo-Saxon kings. 9 Anglo-Saxon England: Forwarding Learning and Law Governing the Kingdom – Anglo-Saxon Law: Like other Germanic peoples, AngloSaxons developed intricate law codes that combined Roman principles with wergeld and other Germanic customs. – Common Law: The Anglo-Saxons were developing their own tradition of common law, which differed from statutory that is based on mandates passed by a legislative body. Common law comes from the Germanic tradition in which the customs of the people are admissible law. 10 Anglo-Saxon England: Forwarding Learning and Law Governing the Kingdom – Witan: This was a small council of powerful and wise men that advised the king; a king could not succeed to the throne without the approval of the Witan. The Witan was a small part of a larger assembly of wise men from across the kingdom, the Witenagemot, which met occasionally with the king to discuss important matters of governance. Young or weak kings tended to be dominated by the Witan. – Royal Offices: In an age of slow communications, the king relied on local representatives, called earls, who administered districts called shires. The king also appointed men to assist the earls and keep them in check, called shire reeves (later, sheriffs). Parish priests and village elders were also co-opted into the ruling system. 11 Anglo-Saxon England: Forwarding Learning and Law Alfred the Great: King and Scholar – Alfred (r. 871-901): This King of Wessex is the only English king known as “the Great” on account of his military victories and his support of learning and culture. He did not learn to read until he was 12, but then did so voraciously, and invited scholars, singers, and performers to court. – Danish Invasion: The invasion of Danes at the time of Alfred’s reign disrupted the Anglo-Saxon political order. Scandinavian invaders crossing the North Sea beginning in the late 700s, and continued. The great monastery at Jarrow was raided and destroyed, while a force of 350 ships raided and plundered London. 12 Anglo-Saxon England: Forwarding Learning and Law Alfred the Great: King and Scholar – “Danelaw”: In response to the Scandanavian invasion, King Alfred reorganized the military and created the first English navy. With a few English victories, Alfred was able to negotiate a treaty with Danish King Guthrum in 886, dividing the country between them. “Danelaw” recognized that a different set of laws ruled over the areas of Danish conquest than in the southern areas held by Alfred. Guthrum also had to convert to Christianity under the treaty’s terms. – Alfred’s Translations: Alfred believed that intellectual ideas should be shared by everyone, a very unusual position at the time. He translated or helped translate works like Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy and Bede’s History from Latin to Old English spoken by most of his subjects. – Height of Anglo-Saxon England: Alfred’s reign marked the height of Anglo-Saxon accomplishment in southern England. 13 England in 866: Divided between Alfred and the Danes 14 Charlemagne and the Carolingians: A New European Empire Charlemagne’s Kingdom – Charlemagne’s Reign: The Carolingian King Charles (742-814) , later known as “Charlemagne” or “Charles the Great” (from the Latin “Carolus Magnus”) represented the highest form of blending of Roman, Germanic, and Christian cultures. He was a great warrior—fighting fifty-three campaigns over his rule—but also possessed a deep intellect and greatly valued education and scholarship. – Administering the Realm: His vast realm, stretching from the Mediterranean to the North Sea, posed many challenges to rule of just one person. Charlemagne did not have fixed sheriffs like the Anglo-Saxons of England, but sent traveling officials called missi dominici to examine and monitor his territory. They often traveled in pairs, such as a bishop and nobleman. – Guaranteeing Loyalty: Charlemagne checked on his nobles by requiring them to attend an assembly twice a year. He departed from Germanic 15 tradition by creating a personal, centralized rule. Charlemagne and the Carolingians: A New European Empire Linking Politics and Religion – Subduing the Saxons: The war-like Saxon peoples of the north had been raiding Frankish territory for generations. Charlemagne sought to subdue them by Christianizing them and incorporating them into his empire. Thirty years of religious coercion brought them under his control; he used religion as a political weapon. – Charlemagne and Irene of Byzantium: Charlemagne tried to unify the church and empires by having his son marry the Byzantine Empress Irene’s daughter, but Irene blinded and deposed her son. He then tried to marry Irene, but these negotiations fell through. – Charlemagne’s Coronation: In 800, Charlemagne came to Rome at the request of Pope Leo III (r. 795-816), who had lost control of Rome. Charlemagne’s forces restored order, and in return, the pope crowned the king the “Holy Roman Emperor,” creating a central alliance between Frankish kings and the papacy. 16 The Empire of Charlemagne, ca. 800 17 Charlemagne and the Carolingians: A New European Empire Negotiating with Byzantium and Islam – Byzantine Relations: The title of emperor irked Empress Irene, but she did not have time to respond since she was overthrown by a Byzantine aristocrat, Nicephorus, in 802. In 813, it was negotiated that Charlemagne would take the title of “Emperor of the Franks” and the Byzantine emperor would have “Emperor of the Romans.” But relations continued to be tense. – Relations with Islam: Charlemagne had much better relations with Harun al-Rashid, the Caliph of Baghdad (r. 786-809). The two exchanged many gifts, including an elephant that the caliph gave to the emperor. Harun also gave Charlemagne nominal control over scared Christian sites in the Holy Land. – Relative Peace and Prosperity: The relative peace within the borders of Charlemagne’s empire led to a period of prosperity, and lucrative 18 trade with the powers of the East. Charlemagne and the Carolingians: A New European Empire An Intellectual Rebirth – Establishing Schools: An Anglo-Saxon scholar from York, England, Alcuin (ca. 730s – 804) visited Charlemagne’s court and so impressed the leader that he invited to become a resident of the court and help the emperor establish institution of learning. – Curriculum: Alcuin brought in scholars from across Europe, and together they established what would become basis for university curricula in Europe: the trivium (grammar, rhetoric, and logic); and the more advanced quadrivium (arithmetic, music, geometry, and astronomy). Medieval scholars saw all of these subjects as deeply related, reflecting patterns by which God organized the world. 19 Charlemagne and the Carolingians: A New European Empire An Intellectual Rebirth – Correcting Texts: Before the printing press, books were created by hand. It could take a full day for a scholar to copy 6-10 manuscript pages. Scribes were in short supply; more people could read than write. Copyists often were not fluent in Latin and made many mistakes. Scholars at Charlemagne’s court sought to correct errors in important texts by comparing different versions and figuring out the correct one. They also developed a standardized method of writing, eliminating many variations that caused confusion. [The next page shows how difficult reading this writing could be!] 20 Photo credits: a) By permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library; b) Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris 21 Struggle for Order in the Church Monasteries Contribute to an Ordered World – Monasteries: Benedict of Nursia (ca. 480-543) had started the tradition of monastic and convent life, with communities living strictly regimented lives under a monastic leader. Monastic life proved popular, and provided one of the few avenues of social mobility. They also provided an essential service of copying, transmitting, and preserving texts and learning. – Monasteries and Politics: Nobles and kings often exerted influence over their local bishops and priests, which seemed to subsume spiritual life to earthly politics. – Cluniac Reform: In 910, a group of monks persuaded a duke in southern France to fund a new monastery at Cluny that was exempt from local control, and accountable only to the pope. Several other monasteries followed suit, becoming accountable to the abbot at Cluny 22 and thus to the pope, avoiding local politics. Order Interrupted: Vikings and Other Invaders Competing for the Realm: Charlemagne’s Descendents – Charlemagne’s Descendents: He had only one son, Louis the Pious (r. 814-840), who inherited his empire, and under whose rule there were already signs of the eventual disintegration of the empire. – Civil War: After Louis’s death, civil war broke out between Louis’s three sons: Charles the Bald (r. 843-877) Lothair I (r. 840-855) Louis the German (r. 843-876) 23 Order Interrupted: Vikings and Other Invaders Competing for the Realm: Charlemagne’s Descendents – Treaty of Verdun: This agreement between the three brothers made in 843 destroyed Charlemagne’s united Western Europe by dividing into three. It also anticipated future European national divisions because linguistic divisions played a part in the division. – The Strasbourg Oaths: When Charles the Bald and Louis the German took oaths to respect the treaty, the oaths were pledged in two different languages: Charles did so in a Romance (Latinderived language), while Louis used an early Germanic tongue. 24 Partition of the Carolingian Empire, 843—Treaty of Verdun 25 Order Interrupted: Vikings and Other Invaders Competing for the Realm: Charlemagne’s Descendents – Kingdom of Lothair Split Up: By 870, Charles and Louis split up the weaker middle kingdom, creating a tradition of disputed lands that continued down to the twentieth century (as in the case of Alsace Lorraine on the German-French border). – Invasions Weaken the Carolingians: The rulers may have recovered the Carolingian empire at some point, but invaders from the north, south, and east weakened them. These included the Magyars (Hungarians) from the east, the Muslims from the south, and the Vikings from the north. 26 Invasions of Europe, Ninth and Tenth Centuries 27 Order Interrupted: Vikings and Other Invaders “The Wrath of the Northmen”: Scandinavian Life and Values – Northern Pagans: When Charlemagne converted the Saxons (in what is now northern Germany) to Christianity, the people of Scandinavia (what is now Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and Finland) remained pagan. These peoples worshipped gods who were similar in function to the Greek and Roman gods, but with different names: Wodin, Thor, and Freya (we get some of our English day names from them: Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday). – Scandinavian Life: Scandinavians tended to be farmers, but the growing season in Northern Europe is so short that their society had a tendency toward scarcity. They also tended to be excellent seamen and traders, and goods from all of Europe found their way to Scandinavian farms. 28 Order Interrupted: Vikings and Other Invaders “The Wrath of the Northmen”: Scandinavian Life and Values – Germanic Peoples: Scandinavians were Germanic peoples, but they had much less contact with the Romans than the Germanic people to the south. They preserved their history in spoken prose narratives called sagas, which valued wit and humor as much as strength and courage. They also shared the Germanic passion for revenge, and had a tendencies toward violence. Many Vikings left Scandinavia to take refuge from blood feuds. 29 Order Interrupted: Vikings and Other Invaders “The Wrath of the Northmen”: Scandinavian Life and Values – Viking Ships: Vikings were skilled navigators and had developed highly sea-worthy and quick vessels. They were built of oak and had enough flex built into them to deal with the rough pounding of the North Atlantic. Each could carry between 50 to 100 men, who would man oars on each side. The shallow keel allowed the boats to sail upriver during raids, something most other large European vessels could not do. Viking raiders often escaped before a counterattack could be mounted. One Anglo-Saxon prayers said, “God help us from the wrath of the Northmen.” 30 Order Interrupted: Vikings and Other Invaders Viking Travels and Conquests – Eastern Travels: Some traveled down the Dnieper River to outside the gates of Constantinople. Throughout the 900s, the Byzantine emperor’s personal guards, the Varangians, were Scandinavians. Others traveled down the Volga, founding a strong state known as the Kievan Rus (as discussed in Chapter 6). Others merely raided territories looking for gold, and amassed great hordes. – Western Explorations: Some Vikings sailed across the North Atlantic, establishing a permanent settlement on Iceland, and one that lasted several centuries on Greenland. Norwegian Leif Erikson (970-1035) traveled all the way to the Canadian maritimes, which he dubbed Vinland, which was not permanently settled. They called the native people of North America as Skraelings, which had a 31 derogatory meaning. Order Interrupted: Vikings and Other Invaders Viking Travels and Conquests – European Settlements: Vikings made permanent settlements in Northern France (Normandy), Sicily, and England. Danes had conquered much of the northern England by mid-ninth century. In 1016, King Swein and his son, Canute, sailed for England with a large force and beat the Anglo-Saxon King, Edmund Ironside (r. 1016). Canute became a king of a united England. 32 Order Interrupted: Vikings and Other Invaders An Age of Invasions: Assessing the Legacy – Two-Hundred Years of Chaos: Viking, Magyar, and Muslim invasions disrupted the order that Charlemagne had worked so hard to restore. Charlemagne’s descendents to not uphold his vision of a personal, centralized authority. Learning and scholarship also suffered, as did the authority of the church during the turmoil of the tenth century. Nuns would mutilate their faces as Vikings approached to avoid rape, which would break their vows of chastity. – Vikings Convert: In the eleventh century, the cycle of violence spent itself as many Vikings converted to Christianity. 33 Manors and Feudal Ties: Order Emerging from Chaos Peasants and Lords: Mutual Obligations on the Medieval Manor Mutual Bonds: As early as the 700s, Carolingian nobles began to develop mutual contracts that bound people into specific relationships. These were based on Germanic tribal relationships, but were more ordered and hierarchical: each person was bound to a superior, from the peasantry up to the king. This system evolved slowly over centuries. 34 Manors and Feudal Ties: Order Emerging from Chaos Peasants and Lords: Mutual Obligations on the Medieval Manor Manors: These developed from the old agricultural estates of the Roman Empire. In Western Europe, manors developed a pattern of serfs and lords that held sway for almost 1,000 years. Almost all manors consisted of the lord’s home, outbuildings like barns and mills, and a village where the peasants resided. Fields were laid out in strips dedicated to each family. Animals were grazed in common pastures. Peasants ate very little meat since their animals produced milk and wool for clothes. Oxen were used to plow the hard clay soil of Northern Europe. Forests provided firewood; fallen limbs could be collected, but trees could not be cut down. 35 Figure 7.8 36 Manors and Feudal Ties: Order Emerging from Chaos Peasants and Lords: Mutual Obligations on the Medieval Manor – Serfs: Peasants were at the bottom of the social order, so they had obligations to those above them, but to no one below them. They were personally free (not slaves), but were bound to the land that they worked (those so bound were serfs). – Serfs’ Obligations: Aside from being required to stay put, serfs had to give the lords a percentage of the crops they grew and livestock they raised, and owed him labor as well. Serfs did not owe military service, as it was only the nobles who could fight. Serf women owed the lord a percentage of their domestic work: spinning and weaving. – Lord’s Obligations to the Serfs: He provided equipment and buildings like barns, and also military protection in case of attack. 37 Manors and Feudal Ties: Order Emerging from Chaos Noble Warriors: Feudal Obligations among the Elite – Supporting Fighting Men: Fighting men were expensive but necessary, so feudal society was organized around supporting them. Manors were the basic unit to provide kings with warriors, and it took about ten peasant families to support one mounted knight. – Lords and Vassals: Warriors were bound to their superior through a web of obligation, just like serfs were bound to their lord. Lords would give warriors land in exchange for military service. – Charles Martel (r. 714-741): Charlemagne’s grandfather who defeated the Muslims at Tours, first offered this exchange of land for service. He recognized the advantage of heavy cavalry, but at the same, knew of its expense. This web of obligation evolved out of Martel’s idea. Pledging loyalty, the knight would become the lord’s vassal, a bond for life. 38 Vassal pledging fealty and receiving a fief from his lord. FIGURE 7.9 Drawing illustrating the relationship between a lord and his vassals Photo credit: Universitatsbibliothek, Heidelberg 39 Manors and Feudal Ties: Order Emerging from Chaos Noble Warriors: Feudal Obligations among the Elite – The Fief: The vassal would be given something from the lord that would produce income, whether it be agricultural land or something else. These nobles would not work the land; their serfs would do this for them. – Feudal Complexities: Even the lowest vassal was still a lord to the peasants who worked his fief. Furthermore, sometimes a vassal was bound to several different lords, and if fighting broke out between them, the vassal often would choose the lord who would give him the biggest fief. – Liege Lord: To prevent these situations, kings in eleventh-century France tried to establish the concept of liege lord: a lord to whom vassals owed absolute loyalty. 40 41 42