Essentials Oils Trade Information Brief

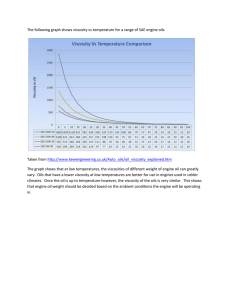

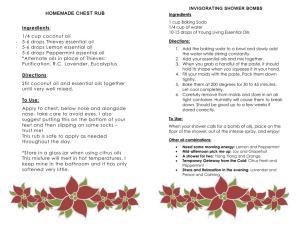

advertisement