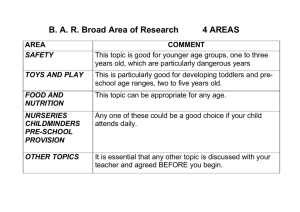

The economic effects of pre-school education and quality IFS Report R99

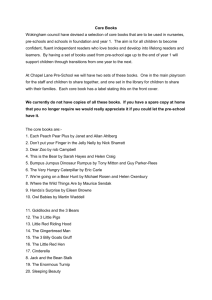

advertisement