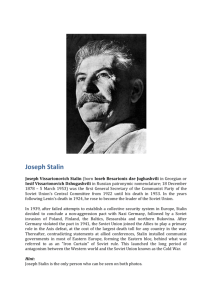

Allocation under Dictatorship: Research in Stalin’s Archives and

advertisement