Document 12090485

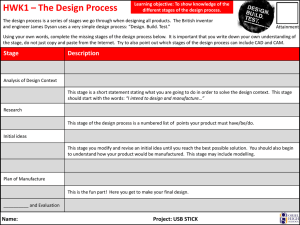

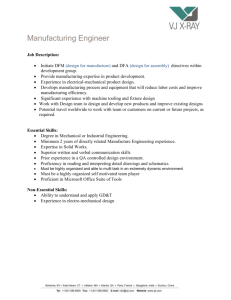

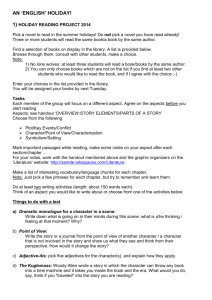

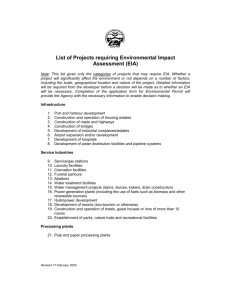

advertisement