California’s Cap‐and‐Trade

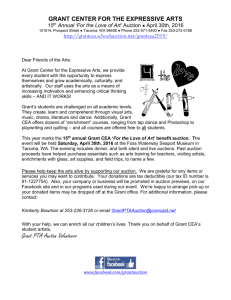

advertisement