Comparison of Public and Private Water Utility

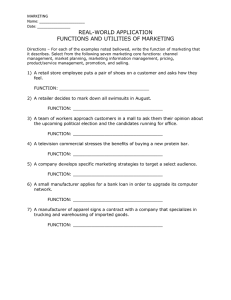

advertisement