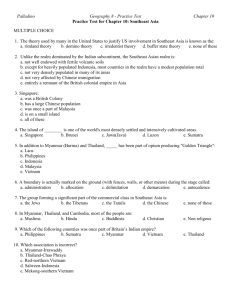

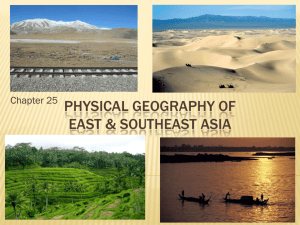

Synchronizing economic integration and security agendas in Southeast Asia: (Add subtitle)

advertisement