siemens.com/energy

Steam Turbines:

Siemens Reactive Blading – designed for highest

efficiency and minimal performance degradation

Russia Power 2014

4-6 March, 2014

Moscow, Russia

Author:

Rudolf Wolf

Ph.D. Klaus Romanov

Siemens AG

Energy Sector

Service Division

Table of Contents

1.0

1.1

Foreword ................................................................................................................ 2

Introduction to Reactive Blading

2.0

Conversion to Reactive Blading.............................................................................. 4

2.1

HPC Casing ............................................................................................................ 4

2.2

Blade Profiles ......................................................................................................... 5

2.3

Shroud Seals ........................................................................................................... 7

2.4

Steam Path Clearances.......................................................................................... 10

2.5

End Seals ............................................................................................................. 11

2.6

Intermediate Seals ................................................................................................ 12

2.7

HPC Rotor............................................................................................................ 14

3.0

Examples of Change in In-Service Performance ................................................... 15

1.0

Foreword

An article in Teploenergetika, N 6, 2005 “Comparison of Active and Reactive High-Pressure

Steam Turbine Cylinders” by A. G. Kostiuk, DEng and A. D. Trukhny, DEng, Moscow Power

Engineering Institute, compared the performance of high-pressure stages and cylinders (HPC) of

active and reactive blading in the turbine flow section as it relates to the design concepts of

various manufacturers. It concludes that it is inappropriate to use reactive blading in supercritical pressure turbines with HPCs of the traditional design.

The authors came to the following conclusions on the basis of materials on hand:

during planned repairs the performance of reactive turbines declines more quickly than

that of active ones;

performance declines as a result of labyrinth seal wear;

restoring reactive turbine performance involves considerable challenges and takes more

time than for active turbines;

a major drawback of the reactive cylinder is the attachment of stator blading directly in

the cylinder inner casing.

To confirm the high performance of reactive blading in Siemens steam turbines, the following

presentation discusses the design of a retrofitted high-pressure cylinder on the K-300-170 turbine

at Greece’s Agios Dimitrios power plant. The HPS retrofit was part of a joint project between

Siemens and Power Machines.

AL:N; ECCN:N

Copyright © Siemens AG 2013. All rights reserved.

Page 2 of 19

This presentation presents the following design features of the retrofitted HPC:

labyrinth and end seals;

blade system, blade attachments;

rotor, inner casing.

Data from 20 power plants were used to analyze the change in the efficiency of Siemens HPCs

and IPCs with reactive blading. A graph of the change in actual (i.e., measured) efficiency over

up to 75 months after commissioning is presented.

1.1

Introduction to Reactive Blading

Karl Gustaf Patrik de Laval developed the active steam turbine more than a century ago (1883).

A year later Sir Charles Algernon Parsons invented the compound reactive turbine. The basic

difference between the two is the choice of stage reactivity.

Stage reactivity means the ratio of the available blade system thermal head to the available

turbine stage thermal head. A turbine is called a reaction turbine if the reactivity at the average

diameter is about 0.5, i.e., the stage head is converted into flow energy half in the vane system

and half in the blade system.

Distributing the thermal head in a stage in this way leads to approximately identical flow

accelerations in the vane and blading system channels. For this reason vanes and blades may

have identical profiles, which is advantageous in manufacturing them.

Distributing thermal head to the vane and blade system in this way results in moderate mean

accelerations in the channels and therefore to profile and secondary losses that are lower in

comparison to an active stage.

Hence the pressure drop to the reactive stage is also distributed equally between vanes and

blades. As a result the turbine rotor is exposed to fairly high axial force, which requires the

installation of a dummy rotor in single-flow cylinders.

Although it is theoretically possible to build a stage with any reactivity from 0 to 1, since the

invention of the steam turbine, i.e., for more than a century, all axial turbine manufacturers

worldwide have adhered to following the principle - either a low-reactivity turbine or a reactive

turbine.

The only thing that both groups have in common is that all blading rows have almost identical

reactivity.

Another commonality is that, for more than a hundred years, manufacturers have been arguing

over which turbine type is better. The discussion is still going on.

But they often forget that both types of turbines have advantages depending on the application

and boundary conditions.

GE Energy/USA, TOSHIBA/Japan, HITACHI/Japan, TURBOATOM/Ukraine, and

LMZ/POWER MACHNES/ Russia make turbines with active steam path blading.

AL:N; ECCN:N

Copyright © Siemens AG 2013. All rights reserved.

Page 3 of 19

SIEMENS/Germany, ALSTOM/France, MITSUBISHI/Japan, and WESTINGHOUSE/USA

make turbines with reactive steam path blading.

Recently GE Energy/USA and LMZ/POWER MACHNES/ Russia have manufactured a series of

turbines with reactive blading.

An example of a successful application of reactive blading in a HPC is the retrofit of an LMZ K300-170 at a power plant in Greece.

2.0

Conversion to Reactive Blading

The existing Leningrad Metals Plant K-300-170 turbine, delivered in 1978 to the Agios

Dimitrios power plant in Greece, had operated for about 100,000 hours and had been retrofitted

by the Siemens - Power Machines consortium in 2008.

The following work was done during the retrofit:

- replacement of the entire steam path while retaining outer casings.

the IPC and LPC were a Power Machines steam path.

New active blading with the same number of stages is used in the IPC and LPC.

The HPC was a Siemens steam path.

The HPC steam path was converted from active to reactive blading.

The existing 12 active blading stages were replaced with 20 reactive blading stages.

The left flow was equipped with a control stage with nozzle steam distribution and 10 stages in

an inner casing; the remaining 9 stages were in the blading carrier, forming the right flow.

2.1

HPC Casing

The HPC consists of two casings: outer and inner. Both are horizontal split casings.

The outer casing underwent non-destructive examination to determine its further service life.

AL:N; ECCN:N

Copyright © Siemens AG 2013. All rights reserved.

Page 4 of 19

The seats for the inner casing, nozzle blade carrier and end seal casings were machined.

The HPC inner casing was replaced with a new horizontal split casing with blades installed in

casings slots.

The inner casing wall is somewhat thicker than in the previous active HPC, which made it

possible to approximate an axisymmetric design, which supports uniform heating, lowers the

possibility of buckling and, as a result, increases maneuverability.

The halves of the inner casing are attached with special bolts and studs to prevent steam from

swirling on the outer surface of the inner casing.

The secondary flow nozzle blade carrier also has a horizontal split and a somewhat larger wall,

which ensures uniform heating, reduces the possibility of buckling and, as a result, increases

maneuverability.

The design of the inner casing and nozzle blade carrier help keep the bore cylindrical during

variable and transient turbine operating modes. It also guarantees that circumferential clearances

will be retained and prevents grazing in the steam path, seal wear and increased leakage.

Axial forces on the rotor caused by the new reactive HPC blading are balanced under any

operating conditions. A residual axial force of 30-100 kN determined the diameter of the

intermediate seal and was adapted to Power Machines’ requirements for retrofitting IPCs and

LPCs using active blading.

2.2

Blade Profiles

All stages except the control stage are reactive. Reactivity is about 50%.

To achieve maximum turbine efficiency, all stages were equipped with blades with a swirl (3Dprofile). These are tapered twisted blades (F-profiles) which optimally conform to various flow

characteristics at different sections along the height of the blade. In addition to the threedimensional foil profiling, these blades are also distinguished by a reactivity selected

individually for each stage from 0.1 to 0.6.

Blades and vanes are made with integrally machined platforms and integrally machined rhombic

T- and L-shaped root attachments that determine the spacing of the nozzle and blade systems.

Only high-heat, erosion-resistant materials (10-13% chromium steel) are used.

AL:N; ECCN:N

Copyright © Siemens AG 2013. All rights reserved.

Page 5 of 19

material:

Vanes

X22CrMoV12-1

Blades

X22CrMoV12-1

Blades and vanes are inserted and caulked in the appropriate slots on the inner casing/guide vane

and rotor carrier.

When blades and vanes are installed in the groves using the special assembly process, they

wedge against one another circumferentially (by the twisting of the platform relative to the root).

In this way, after the last blade or vane is installed, those with a T-shaped root attachment in one

row are pre-stressed at the root and shroud. In blades with L-shaped roots, stress is created only

at the shroud. Depending on the blade or vane type, stress is monitored by measuring the degree

of twist of the roots and shroud.

AL:N; ECCN:N

Copyright © Siemens AG 2013. All rights reserved.

Page 6 of 19

Measurement of blade/vane torsion

The wedging of the blade row provides very good damping of frequency and stochastic

excitations from the steam flow.

The slots needed to install blades in the rotor slots are covered by the blade root, which is

connected to the rotor by a tapered or threaded pin. The type of pin depends on the centrifugal

forces on the last blade.

This modification ensures high reparability if blades have to be replaced.

After all blades of one row are inserted, their shrouds form an outer winding, which is then

surfaced to obtain the seal geometry.

2.3

Shroud Seals

HPC blades have a comparatively low height-to-width ratio. Blades with a short height and

relative large shaft diameter have a relatively large seal clearance if the clearance relative to the

steam path is equal. Losses through seals at short blades are therefore relative large. The seals

are also relatively short compared to end seals. The choice of the optimum seal design for the

HPC blades is vital.

The relative expansion of the rotor relative to the cylinder is decisive in selecting the seal type.

Labyrinth seals were selected as the seals between the rotor and blades and the seals between

blades and casing on the basis of calculations and the values for the relative expansion of the

HPR on the K-300-170 at Agios Dimitrios.

AL:N; ECCN:N

Copyright © Siemens AG 2013. All rights reserved.

Page 7 of 19

Inner casing

Vanes

Rotor

Rotor

This type of seal has better performance than other types and reduces peripheral leakage.

Photographs of steam leaks in seals

Shroud seal design

AL:N; ECCN:N

Copyright © Siemens AG 2013. All rights reserved.

Page 8 of 19

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

(5)

(6)

(8)

(9)

(7)

Line diagram of a reactive stage with shroud seal

(1) inner housing, (2) rivet, (3) lug, (4) blade, (5) vane, (6) rotor, (7) rivet, (8) lug, (9) wrought

wire

To reduce losses in the seals in blades and vanes (4, 5), in the inner casing (1) and in the rotor (6)

seal lugs (3, 8) are caulked. Cylindrical slots are drilled on the blade/vane (4, 5) shroud opposite

the lugs. These cylindrical slots are stepped so that the steam flow swirls more intensely and the

sealing action is therefore increased. Sealing lugs (3, 8) caulked in the rotor and inner casing

with wire (9) are reinforced for strength. They also support optimum radial clearances. If there is

grazing, they abrade without releasing a lot of heat. Later, when the specified clearances are

restored, the sealing lugs are easy to renew.

This seal design (sealing winding and wrought wire) greatly facilitates the replacement of worn

seals during repair.

Sealing winding in the required size is supplied in a roll.

Fragment from a drawing of the steam path of the retrofit HPC in the K 300 – 170, unit 3,

Agios Dimitrios

AL:N; ECCN:N

Copyright © Siemens AG 2013. All rights reserved.

Page 9 of 19

Blade and vane shroud and radial seals take the form of labyrinth seals, a slot on the blade and

vane shroud, and seal lugs in the rotor and in the inner casing. Seal lugs are made of strip

crimped into the slot with wire. The design supports low-cost replacement if the lugs are

damaged.

2.4

Steam Path Clearances

Radial clearances are set for possible deformation of the inner and outer casings on the one hand

and for flexure of the high-pressure rotor on the other. These deformations may occur in nonsteady-state operating modes, e.g., during start and shutdown.

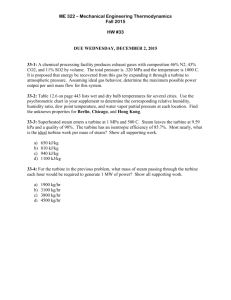

The following table presents data on the axial and radial clearances of the retrofit HPC in

the 300 – 170, unit 3, Agios Dimitrios

Name

Axial

clearance,

mm

Radial

clearance,

mm

Between shrouding and seal lugs on the inner casing (stages 110) and blading carrier (stages 1-9)

0.9 + 0.1

Between the vane shroud and rotor seal lugs

0.9 + 0.1

Inner casing and blade

(stages 1-10), turbine side

7.2

Inner casing and blade

(stages 1-10), generator side

3.7

AL:N; ECCN:N

Copyright © Siemens AG 2013. All rights reserved.

Page 10 of 19

Name

Axial

clearance,

mm

Carrier (stages 1-9) and blades (rows 1 through 9), turbine side

6.7

Carrier (stages 1-9) and blades (rows 1 through 9), generator side

3.7

2.5

Radial

clearance,

mm

End Seals

The end seals’ operating principle is based on reducing steam pressure by throttling, i.e., the

velocity of steam at entry to the labyrinth seal chamber formed by two lugs is damped in it by

swirling.

The number of seal lugs depends on the amount of pressure that has to be reduced, which

determines the required sealing principle and the possible design length.

There are steam chambers within the seals. Steam entering these chambers is drawn off to do

work elsewhere in the turbine.

The remaining small amount of steam-air mixture is discharged to the steam-air mixture

condenser.

The end seals of the retrofit HPC’s outer casing, consisting of 12 rows of segmented seals on the

turbine side and 11 rows of segmented seals on the generator side, were replaced with new,

upgraded ones with coil springs.

Coil springs are far more elastic than the leaf springs used previously and ensure the increased

flexibility of the segments when the shaft neck moves so that clearances are preserved.

All 23 rows of segmented seals were made anew according to the seat dimensions that resulted

after the end seal casings were bored.

AL:N; ECCN:N

Copyright © Siemens AG 2013. All rights reserved.

Page 11 of 19

The drawing shows the dimensions of one of the 23 rows of end seals in the HPC at unit 3 at

Agios Dimitrios. Radial clearances are 0.75 mm. Axial clearances are 3.3 mm on the generator

side and 2.7 mm on the turbine side.

2.6

Intermediate Seals

In turbines with modified flow direction, as on the K 300-170 turbine, intermediate (inner)

seals protect the inner secondary flow steam space from steam leakage from the steam inlet area.

Inner casing/vane system intermediate seals, 8 rows of segmented seals, were replaced with new,

upgraded ones with coiled springs. Around an intermediate seal, the zone of low relative

expansions, labyrinths are formed by opposite lugs.

Seal lugs of shaped strip similar to shroud steals are caulked into the rotor and segments.

Intermediate (labyrinth) seals with caulked lugs to improve their performance come with an extra

abradable NiCrAl layer.

Losses in seals with an abradable layer are 20-30% lower.

Abradable coating

Clearance between assemblies

Clearance between assemblies

Reduced clearance

Approximate composition of the abradable coating

Ni-Cr matrix

Bentonite particles

Bearing material Connecting layer

AL:N; ECCN:N

Copyright © Siemens AG 2013. All rights reserved.

Page 12 of 19

NiCr l is the material applied between caulked lugs. Layer thickness is selected so that the ends

of the seal lugs on the rotor rest on the abradable layer. The material is easily ground by the lugs

resting against it. Because of its alloyed base, the material is resistant to the steam flow

If the clearances shrink until the point when contact occurs, the abradable material wears and

creates an additional labyrinth seal chamber.

Design of the intermediate seal of the retrofit LMZ K 300-170 turbine. Drawing fragment.

.

When the K 300-170 at unit 3, Agios Dimitrios, was retrofit, the abradable layer was 0.6 mm.

The clearance along the seal was 0.6 mm.

Reliable turbine operation without grazing in all modes is key to 100,000 hours between repairs

and is achieved by using modern analytical methods as part of the company’s accepted standards

and processes.

One of the basic, important engineering processes is the determination of relative thermal

displacements and clearances in a turbine.

We can see the results of using these analytical tools and processes during planned repairs and

inspections of turbine units, in which the wear of end tightened blades is low and easily

predictable (0.20 - 0.25 mm.)

AL:N; ECCN:N

Copyright © Siemens AG 2013. All rights reserved.

Page 13 of 19

Rear end seal, PP/Finland, after 100,000 operating hours

Intermediate HP stage, PP/Germany, after 100,000 operating hours

2.7

HPC Rotor

The low-alloyed, high-heat ferritic steels (1%-CrMo(Ni)V) used for a turbine rotor for operation

at temperatures above 350°C gain their optimum performance properties, i.e., a good correlation

of fatigue and viscosity properties, from the appropriate alloying and heat treatment. The use of

these materials makes it possible to extend service life to 200,000 hours and carry out up to

2,200 turbine starts (200 cold, 400 warm and 1,600 hot) according to design criteria.

HPR solid forged without axial channel with reactive blading. Flexible rotor.

The new HP rotor was tested for an overspeed up to 125% of nominal for 2 minutes on the basis

of a multi-dimensional high-speed balancing program per ISO 1940, class G1.0. to G2.5.

This corresponds to an amplitude at G2.5 balancing quality from a peak of about 8 µm “zero to

peak” for operation according to Siemens manufacturing notices.

AL:N; ECCN:N

Copyright © Siemens AG 2013. All rights reserved.

Page 14 of 19

The HP rotor was balanced during manufacture with balancing weights installed in the balancing

slot.

Balancing slots are used instead of balancing holes for more precise balancing.

The rotor has four balancing planes. Two balancing planes are on the blading end planes. One

balancing plane is in the area of the adjusting wheel. These balancing planes are accessible only

when the cylinder is open.

The forth plane is on the HPR-IPR half coupling. The design is based on radial bolts and the

corresponding holes, which can be used for field balancing.

material:

weight (without blades/vanes);

weight (with blades/vanes):

rotor

30CrMoV511

about 11,500 kg

about 12,500 kg

Critical number, shaft oscillations when crossing the critical point

The HPR’s critical speed is 2,178 rpm in the shaft line, which is far higher than half the nominal

speed, and helps prevent low-frequency vibration.

3.0

Examples of Change in In-Service Performance

There are various curves to describe the decline in steam turbine steam path performance. The

decline in performance can be calculated per ASME, DIN, etc.

DIN curves for a decline in performance are calculated before 24 months of operation.

ASME curves for a decline in performance are calculated before 48 months of operation.

For ASME there is an extension of the curve for decline in performance beyond 48 months that

is justified by Siemens Westinghouse data.

In past years Siemens has performed a number of post-retrofit tests. The results showed that the

ASME performance reduction curve yields far higher performance reduction figures than the test

results.

To determine the correction for the decline in performance of a turbine steam path, Siemens

developed a program to determine HPC and IPC efficiency for a number of power plant heat

cycles. The existing power plant heat cycle measurement points were captured by the program.

Parameters were recorded over a long time using standard instruments according to the program

with the power plants’ approval. Measurements were taken when comparable loads were

achieved in a stabilized mode at 15 minute intervals. Measurements were taken with a standard

VIN-TS instrument. The measurements were used to determine HPC and IPC efficiency.

The studies produced the following results:

Power Plant/Germany

AL:N; ECCN:N

Copyright © Siemens AG 2013. All rights reserved.

Page 15 of 19

- monitoring with standard instruments

- thermal tests using calibrated instruments

ASME performance degradation curve

The performance degradation curve based on the measurements yields a performance

degradation of 1.5% over 50 months. Performance degradation per ASME can be calculated at

4%.

Thermal tests using calibrated instruments were performed at the PP/Germany power plant after

6 months and after 36 months of service. The results confirmed calculations based on

measurements with standard instruments.

AL:N; ECCN:N

Copyright © Siemens AG 2013. All rights reserved.

Page 16 of 19

The results of a study at the different power plants at 30-40 months for an HPC with reactive

blading [show[ that the rate of performance loss was 2%.

Performance degradation curves based on the data yield a high probability that the performance

degradation after 120 months of operation will be 3.0% to 3,5%.

The results of a study at the different power plants after 30-40 months for an IPC with reactive

blading [show] that the rate of performance loss was 0.75 % [sic].

Performance degradation curves based on the data yield a high probability that the performance

degradation after 120 months of operation will be 1% to 1.5%.

These conclusions give reason to assume that the use of reactive blading with cutting edge

turbine building technology makes it possible to develop a highly economical and reliable

turbine design. This design can be successfully used to retrofit turbines with active blading.

The authors of the article had a high opinion of reactive blading:

“...when reactive turbine HPCs are built using the Siemens ideology, the performance of the HPP

can be sufficiently stable over the entire time between repairs...”

We are grateful to the authors for this high opinion.

AL:N; ECCN:N

Copyright © Siemens AG 2013. All rights reserved.

Page 17 of 19

1.

References

[1] Kostiuk A. G., DEng, Trukhny A. D., DEng, 2005:

Comparison of Active and Reactive Steam Turbine High-Pressure Cylinders,

Teploenergetika N 6

[2] F. Simon, H. Oenhausen, R. Burchner, K. Y. Eich, 1997

Active or Reactive Blading? Combined!

2

Disclaimer

These documents contain forward-looking statements and information – that is, statements

related to future, not past, events. These statements may be identified either orally or in writing

by words as “expects”, “anticipates”, “intends”, “plans”, “believes”, “seeks”, “estimates”, “will”

or words of similar meaning. Such statements are based on our current expectations and certain

assumptions, and are, therefore, subject to certain risks and uncertainties. A variety of factors,

many of which are beyond Siemens’ control, affect its operations, performance, business strategy

and results and could cause the actual results, performance or achievements of Siemens

worldwide to be materially different from any future results, performance or achievements that

may be expressed or implied by such forward-looking statements. For us, particular uncertainties

arise, among others, from changes in general economic and business conditions, changes in

currency exchange rates and interest rates, introduction of competing products or technologies by

other companies, lack of acceptance of new products or services by customers targeted by

Siemens worldwide, changes in business strategy and various other factors. More detailed

information about certain of these factors is contained in Siemens’ filings with the SEC, which

are available on the Siemens website, www.siemens.com and on the SEC’s website,

www.sec.gov. Should one or more of these risks or uncertainties materialize, or should

underlying assumptions prove incorrect, actual results may vary materially from those described

in the relevant forward-looking statement as anticipated, believed, estimated, expected, intended,

planned or projected. Siemens does not intend or assume any obligation to update or revise these

forward-looking statements in light of developments which differ from those anticipated.

Trademarks mentioned in these documents are the property of Siemens AG, its affiliates or their

respective owners.

AL:N; ECCN:N

Copyright © Siemens AG 2013. All rights reserved.

Page 18 of 19

Published by and copyright © 2013

Siemens AG

Energy Sector

Freyeslebenstrasse 1

91058 Erlangen, Germany

Siemens Energy, Inc.

4400 Alafaya Trail

Orlando, FL 32826-2399, USA

For more information, please contact

our Customer Support Center.

Phone: +49 180/524 70 00

Fax: +49 180/524 24 71

(Charges depending on provider)

E-mail: support.energy@siemens.com

All rights reserved.

Trademarks mentioned in this document are

the property of Siemens AG, its affiliates, or

their respective owners.

Subject to change without prior notice. The

information in this document contains general

descriptions of the technical options available,

which may not apply in all cases.

The required technical options should therefore

be specified in the contract.

AL:N; ECCN:N

Copyright © Siemens AG 2013. All rights reserved.

Page 19 of 19