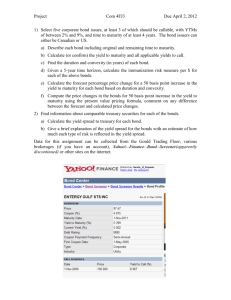

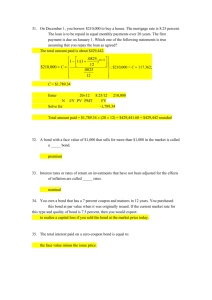

R Y B

advertisement