MA-Thesis-FINALDraft_WHITESOCK_042012

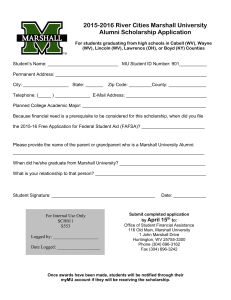

advertisement