Section 1. Current Scientific Evidence on Glycemic Control and

advertisement

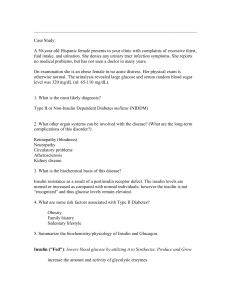

Section 1. Current Scientific Evidence on Glycemic Control and Targets: The Noncritically Ill Hospitalized Patient A 58-year-old obese woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus is admitted for treatment of an infected diabetesrelated foot ulcer. There is a 20- x 10-cm area of cellulitis surrounding the ulcer, which has some purulent drainage and contains significant fibrinous material. The patient is started on intravenous (IV) antibiotics. The surgeons have requested that she be kept nothing by mouth (NPO) after midnight for surgical debridement in the morning. Her current weight is 100 kg (body mass index [BMI] 38), and her recent glycemic control can be summarized as having blood glucose values that are usually in the mid 200s mg/dL and a recent glycosylated hemoglobin (A1c) measurement of 11.2%. Her home medical regimen includes glipizide 10 mg twice daily, metformin 1000 mg twice daily, and exenatide 10 mg subcutaneous twice daily. Her blood glucose in the emergency department is 292 mg/dL. Which statement is MOST correct about the role of glycemic control in this patient’s care? o A. There is evidence from randomized-controlled trials supporting tight glycemic control in this type of patient. Optimal glucose target is below 110 mg/dL. o B. There is evidence from randomized-controlled trials supporting tight glycemic control in this type of patient. Optimal glucose target is below 180 mg/dL. o C. There are observational data demonstrating an association between poor outcomes and hyperglycemia in this type of patient. Optimal glucose target is uncertain. o D. There are no data linking glycemic control to outcomes in this type of patient. Optimal glucose target is uncertain. Answer: C. There are many observational trials demonstrating an association between hyperglycemia and adverse clinical outcomes in hospital patients. The patient in this case requires active management of her blood glucose levels given her poor baseline blood glucose control and her current active medical and surgical issues. The optimal glycemic target is uncertain, although maintaining a blood glucose level below 180 mg/dL would be generally in accord with expert recommendations. Current Scientific Evidence on Glycemic Control and Targets: The Noncritically Ill Hospitalized Patient There is substantial evidence demonstrating an association between hyperglycemia in hospitalized patients and adverse outcomes.1-6 As an example, Umpierrez et al showed that 38% of patients admitted to their hospital suffered from hyperglycemia, and 33% of these patients had not been diagnosed with diabetes prior to the hospital admission. The patients with diabetes and hyperglycemia had a significantly higher in-hospital mortality than the patients with normal blood glucoses (3% vs 1.7%), but the patients with hyperglycemia that were not known to have diabetes had the highest mortality of all (16%).2 Other cohort studies have also shown associations between hyperglycemia and infections.3-5 Several randomized trials have evaluated the effects of targeting “euglycemia” in intensive care unit (ICU) patients. Unfortunately, there have been no comparable randomized studies in noncritically ill hospitalized patients. Without randomized trials, clinicians try to extrapolate from the conflicting results of the ICU trials, which may not apply to noncritically ill patients. Moreover, the overall management goals for the noncritically ill are unclear. Is the goal to only avoid severe illness related to hyperglycemia, such as diabetic ketoacidosis; to avoid moderate levels of hyperglycemia and its pathophysiologic implications; or to achieve true euglycemia in hopes of preventing all theoretical adverse consequences of hyperglycemia in a patient with active illness? Currently, hospitalists are saddled with the responsibility of managing inpatient diabetes and hyperglycemia without good data to define specific glycemic targets or treatments. Although some argue that the lack of data on the subject means that we should not waste our time discussing it, the subject is ubiquitous and difficult to ignore. At the time of admission to the hospital, most patients with diabetes hand over the management of their blood glucose levels to the doctors and nurses. Given the lack of strong scientific data, clinicians often turn to expert opinion for a rational approach. Most of the recommendations in this module are based on the opinions of experts.1,7-9 In a consensus statement, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists have recommended that fasting blood glucoses should be below 140 mg/dL, and random glucoses should be below 180 mg/dL when patients are in the hospital, as long as this can be safely achieved (Table 1).7 However, these values are given only as guidance and the authors note that glycemic control should be individualized. These recommendations are based solely on the opinion of experts, as opposed to scientific trial evidence. Critics call the goals arbitrary and lament that they are potentially difficult to achieve. In summary, there are abundant studies demonstrating an association between hyperglycemia and adverse outcomes in hospital patients, and there are practical reasons for controlling blood glucose levels in hospitalized patients. However, there is not strong evidence supporting any specific glucose target for noncritically ill hospitalized patients. Expert recommendations offer some guidance. Section 2. Controlling Blood Glucose Levels in the Hospital: Which Medications Are Best A 58-year-old obese woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus is admitted for treatment of an infected diabetesrelated foot ulcer. There is a 20- x 10-cm area of cellulitis surrounding the ulcer, which has some purulent drainage and contains significant fibrinous material. The patient is started on IV antibiotics. The surgeons have requested that she be kept NPO after midnight for surgical debridement in the morning. Her current weight is 100 kg (BMI 38), and her recent glycemic control can be summarized as having blood glucose values that are usually in the mid 200s mg/dL and a recent A1c measurement of 11.2%. Her home medical regimen includes glipizide 10 mg twice daily, metformin 1000 mg twice daily, and exenatide 10 mg subcutaneous twice daily. Her blood glucose in the emergency department is 292 mg/dL. Which of the following treatment modalities would be MOST consistent with expert recommendations in this situation? o A. Continue her outpatient medications for diabetes, but add a dose of glargine insulin before bedtime and an insulin sliding scale. o B. Discontinue her diabetes medications and initiate sliding scale insulin to estimate her insulin needs. o C. Discontinue her diabetes medications and initiate scheduled glargine, scheduled short-acting insulin given with meals, and an insulin sliding scale. o D. Increase the dose of her home diabetes medications. Answer: C. The patient in the case should be given scheduled basal and nutritional insulin. Controlling Blood Glucose Levels in the Hospital: Which Medications Are Best Medications to treat hyperglycemia in the hospitalized patient should have the following characteristics: Act rapidly Allow for rapid titration (ie, increases and decrease in doses should have immediate effects) Have safety monitoring (ie, glucose testing) Insulin is the medication that most often meets these criteria, and it is the medication on which the remainder of this module will focus. I believe that most noncritically ill patients who demonstrate blood glucose levels that are consistently outside of the target range should be treated with subcutaneous insulin. Most other diabetes medications have shortcomings when used in patients that are ill enough to be hospitalized. 1 Table 2 summarizes the issues that should be considered when using noninsulin diabetes medications in the hospital, and illustrates why insulin is regarded as the medication of choice for controlling blood glucose in ill patients.8 There are situations, such as a patient nearing discharge, where the use of oral medications (or other noninsulin medications) is appropriate. Although insulin is the drug of choice for managing insulin in the hospitalized patient, it is important to recognize that insulin has historically been associated with high rates of adverse events, especially hypoglycemia, when used in the hospital. Therefore, many experts believe that insulin use in hospitals should be standardized to assure patient safety and reduce insulin-related errors. In the multiple choice question for this section, the answer is relatively straightforward because this patient should be treated with insulin regardless of her acute hospitalization based on her recent blood glucose levels and her A1c level. Continuation of her oral medications would, at best, maintain her poor control. The addition of other noninsulin agents in this case would not have a rapid effect on her glycemic control and would be unlikely to achieve adequate control. Because the patient will be NPO after midnight, her sulfonylurea should be held to reduce the likelihood of hypoglycemia in the fasting state. Metformin should be held in the perioperative setting where there is an increased likelihood of hemodynamic changes or changes in renal function which could increase the risk of metformin-induced lactic acidosis. Exenatide has not been well studied in the inpatient setting and carries the risk of nausea, gastroparesis, and pancreatitis. A once-weekly formulation (pending US Food and Drug Administration approval), with its long duration of action (up to 4–6 week), will pose a management challenge to the inpatient provider. Providers will have to prescribe appropriate amounts of insulin, likely at lower doses than most formulas would recommend, to account for the glucagon-like peptide-1 medication. Therefore, this patient’s home regimen should be held, and she should be treated with insulin. Answer B (initiate a short-acting insulin sliding scale) is what many physicians would do in this case. An insulin sliding scale used in isolation is designed to provide insulin to patients who need insulin only on an intermittent basis. Sliding scale insulin should not be used alone in this scenario because the patient is demonstrating consistent hyperglycemia. When using a sliding scale, patients receive insulin only after they experience hyperglycemia (ie, the insulin is given reactively). Because the patient in the case is demonstrating consistent hyperglycemia, it is preferable to give insulin in an anticipatory way (ie, preemptively) to maintain the patient in a controlled metabolic state. In addition, sliding scales, when used alone, almost never deliver a well-calculated dose of insulin for the particular circumstances. An insulin sliding scale may be appropriately used alone for the occasional patient who does not have a defined need for insulin therapy. As an example, sliding scale insulin may be prescribed for the patient who is being initiated on high-dose corticosteroids, with normal blood glucose levels so far. In that case, it is not certain that the patient will need insulin, and the sliding scale is used as a safety mechanism. For patients with a defined need for insulin (ie, those with a diagnosis of diabetes requiring oral medications or insulin or those exhibiting hyperglycemia), insulin should be given in an anticipatory and physiologic manner. A prospective, multicenter, randomized trial comparing the efficacy and safety of a basal-bolus regimen with that of sliding scale insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes demonstrated that basal-bolus insulin improved glycemic control without and increased rate of hypoglycemia.10 In the RABBIT-2 Trial, patients with type 2 diabetes randomized to basal-bolus insulin achieved a blood glucose target of less than 140 mg/dL in 66% of patients versus 38% of patients on sliding scale. Rates of hypoglycemia, defined as a glucose lower than 60 mg/dL were equal in each group. In summary, patients who demonstrate consistent hyperglycemia in the hospital should be treated with insulin. Other agents are acceptable in some clinical circumstances, but insulin is fast acting, titratable, and almost never contraindicated in hospitalized patients. Although there are a few circumstances where an insulin sliding scale might be used alone, it should be the exception and not the rule. Patients with consistent hyperglycemia need anticipatory and physiologic insulin. Section 3. Step 1: Computing an Appropriate Dose of Insulin to Manage Hyperglycemia in the Hospital A 58-year-old obese woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus was admitted for treatment of an infected diabetesrelated foot ulcer. There is a 20- x 10-cm area of cellulitis surrounding the ulcer that was debrided yesterday and looks much better. Her current weight is 100 kg (BMI 38), and her recent last A1c measurement was 11.2%. The surgical team appropriately stopped her oral diabetes medications, but only placed her on a sliding scale insulin regimen. She is now eating normally and her blood glucose before lunch is 293 mg/dL. How much total insulin would you estimate that this patient would require in a 24-hour period when eating 3 meals? o A. 20 units or less o B. Approximately 30 units o C. Approximately 40 units o D. 50 units or more Answer: D. A weight-based calculation would suggest that the patient will require 50 units of insulin or more in a day when receiving adequate nutrition. Step 1: Computing an Appropriate Dose of Insulin to Manage Hyperglycemia in the Hospital There are many barriers to good glycemic control in the hospital. One of the biggest barriers is deciding how much insulin to prescribe. Physicians who are uncomfortable estimating a patient’s insulin needs are more likely to avoid the use of insulin even when it is appropriate and to underdose the insulin when it is prescribed. The Society of Hospital Medicine’s Glycemic Control Task Force provides guidelines for choosing a starting dose of insulin for hospitalized patients with hyperglycemia.8 The first step is to estimate a patient’s total daily dose of insulin (TDD). The TDD is the total amount of insulin that a patient requires for metabolic control over the course of an entire day when receiving nutrition. That dose includes the patient’s basal insulin needs (longacting insulin such as glargine or neutral protamine Hagedorn [NPH]) and his or her nutritional needs (shortacting insulin such as aspart that is given with meals). There are 2 methods for estimating TDD. Use the first method for patients who are on insulin at home. The home insulin dose can provide a starting point for the hospital insulin dose (even if the type of insulin will be modified). Of course, when using this approach, several other variables must be considered, including the patient’s glycemic control at home (if control is poor at home, the dose may need to be increased), the seriousness of the illness requiring hospitalization (the stress response to illness typically results in an increase in insulin resistance), and changes in nutritional intake. The second method uses the patient’s weight to calculate a starting dose of insulin. Both methods are outlined in Figure 1.8 The patient weights 100 kg and has a BMI consistent with obesity. Therefore, her TDD would be estimated to be at least 0.5 units/kg TDD = 100 kg x 0.5 = 50 units of insulin This means that this patient would be expected to require at least 50 units of insulin over the course of a day, when taking in normal levels of nutrition. The estimates provided in Figure 1 are conservative, and many patients will require higher doses of insulin to achieve metabolic control. However, most patients will not require less insulin (ie, very few patients will suffer severe hypoglycemia at the suggested doses). Still, it is important to remember that these calculations are just estimates, and the initial estimate of the TDD is less important than the subsequent adjustments made to the dosing which are based on the patient’s response. The fear of hypoglycemia often prompts clinicians to underdose insulin in the initiation phase. Perhaps the most common example of this is the use of sliding scale insulin to “see how much insulin the patient needs.” Although this approach is reasonable in a patient with borderline or normal blood glucose values, patients who are already demonstrating consistent hyperglycemia should be treated with scheduled (anticipatory) doses of insulin to achieve glycemic control. In this population, sliding scale insulin will almost always undertreat the patient and will result in an unnecessary delay in arriving at the appropriate TDD. In summary, the first step toward glycemic control in the hospital is to calculate the insulin TDD. Method 1 is to calculate TDD based on the patient’s home insulin doses and make adjustments based on the factors described previously. Method 2 is to calculate TDD using a weight-based formula which takes into account the patient’s likely insulin sensitivity. This is a key step in formulating an anticipatory insulin program. Section 4. Steps 2 and 3: Formulating an Anticipatory, Physiologic Insulin Regimen with Adjustments as Needed A 100-kg 58-year-old obese woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus was admitted for treatment of an infected diabetes-related foot ulcer. There is a 20- x 10-cm area of cellulitis surrounding the ulcer that was debrided yesterday and looks much better. She was previously on oral medications to treat her diabetes. You have estimated that her insulin TDD is 50 units (100 kg x 0.5 = 50). She is now eating normally and her blood glucose before lunch is 293 mg/dL. What is the most physiologic way of delivering 50 units of insulin to the patient? o A. Give the entire amount as 3 doses of rapid-acting insulin (lispro) divided evenly before each meal. o B. Give the entire amount as intermediate-acting (NPH) or long-acting insulin (ie, detemir or glargine) in 1 or 2 injections per day, along with an insulin sliding scale. o C. Give half of the total daily insulin dose (25 units) as a long-acting insulin, and divide the other half to be given with meals. o D. Give insulin by sliding scale, escalating the dose until the target dose is reached. Answer: C. The patient in the case has an estimated TDD of 50 units of insulin. Half of this could be given as glargine, 25 units subcutaneously daily. The remainder could be provided with meals, such as 8 units of a rapid-acting insulin analogue subcutaneously 3 times daily with meals. None of the other answers provide the recommended anticipatory, physiologic insulin. Steps 2 and 3: Formulating an Anticipatory, Physiologic Insulin Regimen with Adjustments as Needed Step 2: Formulating an Anticipatory, Physiologic Insulin Regimen After the clinician estimates the patient’s TDD, the second step is to decide exactly how to deliver the insulin to the patient. Experts recommend that this be done in a way that is anticipatory (as discussed above) and physiologic (ie, the insulin is given in a way that approximates how insulin would be secreted from the pancreas in normal conditions).1,7-9 The use of anticipatory, physiologic insulin results in improved glycemic outcomes compared to the use of an insulin sliding scale alone.10 Quality improvement efforts using this approach have been shown to lead to significant, although modest, improvements in glycemic control in hospitalized patients.11-13 Humans normally secrete a basal level of insulin, even when in the fasting state, which serves to suppress processes such as gluconeogenesis and ketogenesis. When nutrition is ingested, insulin levels quickly rise to allow for the appropriate metabolic handling of the ingested nutrition. When providing exogenous insulin in a physiologic way, it is useful to conceptualize the insulin that is administered as belonging to 1 of 3 different categories–basal insulin, nutritional insulin (also known as meal insulin), and correctional insulin (also known as supplemental insulin). Basal insulin is the component of the insulin that is given in a way that provides a continuous, low level of insulin throughout the entire day. Nutritional insulin is the component that is given to exactly match the patient’s nutritional intake. Correctional insulin is the component of insulin that is given in small doses on an as-needed basis to correct hyperglycemia when it occurs despite the administration of basal and nutritional insulin. Approximately half of the TDD should be given as basal insulin, and the other half should be given as nutritional insulin (the “50/50 rule”). Figures 2 and 3 show the action profiles of the available insulins (colored lines) superimposed on the normal insulin secretion profile (blue shadows).8 These figures emphasize how some insulin analogues have the theoretical advantage of more closely mirroring the physiologic profile. In order to give a constant level of basal insulin, a long-acting, low-peaking insulin (eg, glargine) is preferred (Figure 2). For patients taking their nutrition as boluses (ie, meals or bolus tube feeds), the rapid-acting analogues (eg, lispro, aspart, and glulisine) are preferred for the provision of nutritional insulin (Figure 3). A regimen of exogenous insulin that provides these components as separate insulin injections allows the nutritional insulin to be matched to the actual nutrition (eg, modified depending on the patient’s nutritional intake), without affecting the provision of basal insulin (which should be given regardless of nutritional circumstances). In addition to scheduled doses of basal and nutritional insulin, correctional insulin can be administered as small doses of a rapid-acting insulin or regular insulin (usually the same as the nutritional insulin). Correctional insulin is typically given in a dose that varies depending on the patient’s blood glucose at the time of administration. Correctional insulin is usually ordered and administered in a way that is analogous to what most clinicians refer to as “sliding scale insulin” (see example, bottom of Figure 4). However, correctional insulin differs from traditional sliding scale insulin in that it only intends to provide small doses of additional insulin to correct hyperglycemic variations, it is customized to the patient’s level of insulin resistance, and it is always adjunctive to scheduled doses of insulin. Of the 3 components of insulin discussed here, nutritional insulin is the one that requires the most consideration. Hospitalized patients receive nutrition in a variety of ways (eg, NPO, regular meals, liquid diet, continuous or intermittent tube feeds, and parenteral nutrition). The nutritional insulin must be delivered in a way that matches the nutrition regimen. Table 3 shows the Society of Hospital Medicine Glycemic Control Task Force recommendations for preferred insulin regimens for each of several different nutritional situations.8 The insulin regimens in Table 3 are based on the 50/50 rule (previously mentioned), although there are some minor exceptions. These recommendations call for a reduction of the basal portion of the regimen to 40% of the TDD for patients receiving tube feeds because there is a glycemic burden associated with this type of nutrition (ie, the nutritional insulin needs increase more than basal needs with this type of feeding). Also, parenteral feeding is felt to be best treated by mixing the insulin with the feeding so that it is given intravenously. In addition to matching the type of nutrition, the nutritional insulin must be given in a way that allows the insulin to be timed with the delivery of the nutrition. This is complicated by the inconsistency of nutrition intake and delivery in the hospital. This is further discussed in Section 5: Methods for Matching Nutritional Insulin with the Actual Nutritional Intake. Although the principles discussed here are relatively simple, it can be a challenge to consistently employ them in clinical practice. Attempts to use an anticipatory, physiologic approach to insulin management across an entire unit or hospital can be facilitated by physician and nurse education programs and a standardized order set. Several quality improvement efforts using this approach have been shown to result in significant, although modest, improvements in glycemic control and safety in hospitalized patients. Hospitalists interested in quality improvement related to the hospital management of diabetes and hyperglycemia can find a wealth of resources in the Society of Hospital Medicine Glycemic Control Resource Room (http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/ResourceRoomRedesign/GlycemicControl.cfm). Step 3: Insulin Adjustments Following the Initial Regimen It is important to remember that the initial insulin dose estimate is just that—an estimate. It will, invariably, require adjustment based on the response of the patient. The clinician should critically examine each insulin-treated patient’s blood glucose trend on a daily basis. Although the daily manipulation of insulin doses remains more of an art than a science, one common way to adjust the dose for patients who remain consistently hyperglycemic is to add up all of the correctional insulin administered over the last 24 hours. That correctional total is added to the previous day’s TDD to create a new TDD. Divide the new insulin TDD into the 50:50 regimen as described previously. In summary, after estimating the insulin TDD, the second step to achieving inpatient glycemic control is to divide the TDD into “physiologic” basal and nutritional doses. Approximately half of a patient’s TDD should be provided as scheduled basal insulin, and the other half as scheduled nutritional insulin which is given in a way that matches the actual nutrition that a patient is receiving. Correctional “sliding scale” insulin can be given in addition. After the initial regimen is prescribed, continue to adjust for hyperglycemia by adding the amount of correctional insulin administered over the last 24 hours to the previous days’ insulin TDD. Section 5. Methods for Matching Nutritional Insulin with the Actual Nutritional Intake You have written an order to give 25 units of glargine at bedtime, 8 units of lispro insulin before each meal, and an appropriate correctional scale. The patient tolerated a small breakfast, but at lunch time she tells the nurse that she feels mildly nauseated and is not sure that she will be able to eat her lunch. Her pre-lunch blood glucose is 292 mg/dL. Which regimen BEST manages her nutritional insulin in this situation? o A. Give the 8 units of lispro and the correctional insulin along with an antiemetic drug. o B. Hold the 8 units of lispro but give the correctional insulin. o C. Give half of the prescribed lispro (4 units) and the correctional insulin. o D. Let the patient attempt to eat the meal, and give the lispro insulin after the meal in proportion to her actual intake. Answer: D. The patient in the case is preparing to eat, but it is unclear if she will tolerate the meal. Giving all of the prescribed insulin, holding all of the prescribed insulin, or halving the insulin dose would all be arbitrary (and potentially wrong) decisions because there is no way for the clinician to predict what will happen in this case. Methods for Matching Nutritional Insulin with the Actual Nutritional Intake As already mentioned, the most difficult aspect of providing insulin to the hospitalized patient is matching the administered insulin with the actual nutritional intake. In contrast to basal insulin, which can be provided continuously regardless of nutritional intake, nutritional insulin must be reduced if the nutritional intake is reduced and held completely if no nutrition is provided. Adding to the difficulty is the unpredictability of nutritional intake in hospitalized patients. Nutrition is often held in anticipation of tests or procedures, and nutritional intake can also be interrupted by patient-specific factors such as poor appetite and nausea/vomiting. For this reason, the matching of nutrition and nutritional insulin must be done in real time and at the bedside. In most institutions, this means that this real-time management will be the responsibility of nurses. Some common scenarios and solutions are listed below: 1. The patient is NPO for a test or procedure: - Basal insulin is given as prescribed. Nutritional insulin is held until the patient is no longer NPO. 2. The patient is having nausea or vomiting: - Basal insulin is given as prescribed. Nutritional insulin is held. If the patient is able to successfully tolerate some of the meal, the nutritional insulin should be given in proportion to the total intake of the meal. For example, if half of the meal is consumed, half of the nutritional dose should be given post-consumption. 3. It is time for the nutritional insulin to be given but the tray has not arrived: - Nutritional insulin should be given within 10 to 15 minutes prior to the patient starting his or her meal. The dose should be held until the tray arrives and the patient is ready to eat. There are no easy or “autopilot” techniques for matching nutrition and insulin delivery. Doing it well requires a knowledgeable person to assess the situation, the patient’s current glucose level, and the nutrition that has been, or will be, administered. Only then can the prescribed dose of insulin be given, or modified, appropriately. For situations in which the nutritional intake is uncertain, common sense would suggest that the best approach may simply be to give the insulin after the patient has attempted to eat and to give the insulin in a dose that is proportional to the actual intake. The rapid-acting insulin analogues make this approach attractive because they peak quickly and are still able to have the appropriate effect even when given after the meal. Summary Hospitalized patients with hyperglycemia require medical management. When using subcutaneous insulin in hospitalized patients, an anticipatory, physiologic approach is recommended. This requires the clinician to first estimate the TDD of insulin that the patient will require and secondly to administer it in a physiologic way, matching the nutritional insulin with the type of nutrition that is given. Section 6. Preparing Patients for Discharge Home Your 64-year-old female patient who was initially admitted to the ICU with sepsis and acute renal failure has since recovered and you are planning her discharge. Her medical history is significant for diabetes for which she was previously on metformin 1 g twice daily, glyburide 5 mg once daily, and exenatide 10 µg subcutaneous twice daily. Over the last few days in the hospital, she has been treated with glargine 20 units daily as well as 6 units of short-acting insulin with meals. Her home medications have been held. Her morning glucose for the past 2 days has been 100 mg/dL and 120 mg/dL. She has occasionally required 1 unit of short-acting correctional insulin, but for the most part, her premeal glucose values have been within the recommended range. Her renal function has improved to a creatinine of 1.3 mg/dL with a glomerular filtration rate of 50 mL/min/1.73 m2 which is her baseline. She did have a small troponin leak and her echocardiogram showed an ejection fraction of 50%. Her A1c on admission was 7.9%. What is the BEST discharge diabetes care plan for this patient? o A. Restart all of her home medications at the time of discharge and have her follow-up with her primary care physician (PCP) in 2 to 4 weeks. o B. Have her meet with a diabetes educator, discharge her on her current regimen of insulin glargine and lispro, and schedule a follow-up appointment with her PCP in 1 to 2 weeks. o C. Discontinue her metformin and glyburide. Continue her on exenatide and start her on glipizide 5 mg daily as well as a thiazolidinedione. Have her follow-up with her PCP in 1 to 2 weeks. o D. Discontinue all her home medications and start her on glipizide 5 mg daily, as well as lantus insulin 15 units daily with a correctional short-acting insulin and have her follow-up with her PCP in 1 to 2 weeks. Answer: B. She has proven success on her current regimen. She also will need education regarding insulin administration, a scale for correctional dosage, and a meter with lancets if she does not already have this. If this regimen is not adequate, she can resume her exenatide while on insulin. Preparing Patients for Discharge Home Diabetes has reached epidemic proportions in the United States with nearly 19 million adults with diagnosed diabetes. It is estimated that 7 million adults in the United States have undiagnosed diabetes, with another 79 million estimated to have prediabetes.14 For clinicians, inpatient hospitalization has become an opportunity to review the patient’s history, diagnose diabetes, educate the patient, and adjust the patient’s glycemic control. In addition, the ADA has recently released updated guidelines for diagnosing diabetes that have made the inpatient diagnosis easier. According to the new ADA guidelines, an A1c greater than 6.5% can now be used to make a diabetes diagnosis and individuals with A1c values between 5.7% to 6.4% should be considered at risk for developing diabetes (Table 4).15 In the inpatient setting, only an elevated A1c is appropriate to make a new diagnosis of diabetes as other methods rely on plasma glucose values which may be erroneously elevated due to stress hyperglycemia. With these guidelines, individuals with undiagnosed diabetes can be identified, educated, and have the appropriate needs assessment. We recommend that all patients who have an elevated glucose value on hospital admission have their A1c checked if a recent A1c measurement is not available. Patients with hyperglycemia also should be monitored in the hospital with regular blood glucose checks. This helps to set the foundation for any discharge decisions. Patients with elevated A1c will likely need intensification of their home regimen. If available, all patients with diabetes should be evaluated and educated by a diabetes educator. If there is no specified in-house educator, this role may be filled by any qualified physician, pharmacist, or nurse. In addition, an outpatient referral to a diabetes educator may further benefit the patient. The majority of patients will not need basal bolus insulin after discharge. Reinstitution of oral and noninsulin injectable medications can be started at discharge in patients with acceptable preadmission glycemic control (A1c ≤7%) and without a contraindication to their continued use (Figure 5).16 Other patients may need an increase of prior medications or addition of a second agent. Consideration of ongoing medical problems, health literacy, insurance, and income will all play a part in prescribing a regimen to which the patient can adhere. This may entail switching to mixed insulins or generic prescriptions. If possible, oral medications should be started prior to discharge to ensure that the patient can tolerate such medications. Patients discharged with a new diagnosis of diabetes or on insulin should follow-up with a PCP preferably within 2 weeks of discharge. PCPs should be made aware of any changes in the patient’s medications and patients should have detailed and clear instructions on when to check blood glucose and insulin timing. Education should focus on basic meal planning, medication administration, detection of hyperglycemic and hypoglycemic symptoms, as well as treatment and prevention. Teach back is a useful technique to check for understanding. It is also important for clinicians to identify patients who are at high risk for adverse events or may have trouble adhering to the regimen. Elderly patients are at increased risk for hypoglycemia, especially with multiple insulin injections. Visually impaired patients may benefit from prefilled syringes that have larger numbers or that make clicks with each unit. There are also glucometers that speak to patients who are blind or have significant visual impairments. Patients who do not have insurance or a PCP are unlikely to take expensive new medications. Various community clinics and resources are available, and each hospital should have a list that can be given to such patients. In summary patients with acceptable blood glucose control prior to admission can be restarted on their home regimen. Those who had poor glucose control prior to admission should have their medications adjusted. All patients should undergo education prior to discharge, which should include understanding of signs and symptoms of hyper/hypoglycemia and clear instructions of what to do. Recommendations for timing and frequency of home glucose monitoring should be made, and a healthcare provider who is responsible for ongoing diabetes care and glycemic management should be identified.