View/Open

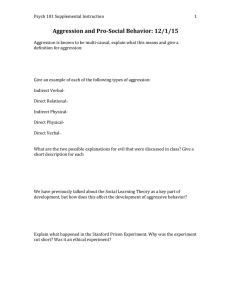

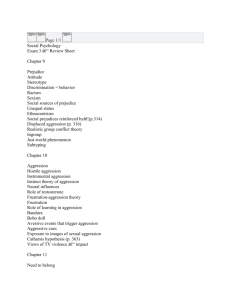

advertisement