a biographical times series analysis

IDENTIFYING JOB EMBEDDEDNESS CHARACTERISTICS IN RÉSUMÉS:

CAN HUMAN RESOURCES PROFESSIONALS IDENTIFY DIFFERENCES?

A Thesis

Presented to the faculty of the Department of Psychology

California State University, Sacramento

Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of

MASTER OF ARTS in

Psychology

(Industrial/Organizational)

Daniel E. Heap

SPRING

2012 by

© 2012

Daniel E. Heap

ALL RIGHTS RESERVE ii

IDENTIFYING JOB EMBEDDEDNESS CHARACTERISTICS IN RÉSUMÉS:

CAN HUMAN RESOURCES PROFESSIONALS IDENTIFY DIFFERENCES?

A Thesis by

Daniel E. Heap

Approved by:

__________________________________, Committee Chair

Greg Hurtz, Ph. D.

__________________________________, Second Reader

Larry Meyers, Ph. D.

__________________________________, Third Reader

Andrew Job, Ed. D.

Date: ____________________________ iii

Student: Daniel E. Heap

I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this thesis is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the thesis.

Jianjian Qin, Ph.D.

Department of Psychology

, Graduate Coordinator

Date iv

Abstract of

IDENTIFYING JOB EMBEDDEDNESS CHARACTERISTICS IN RÉSUMÉS:

CAN HUMAN RESOURCES PROFESSIONALS IDENTIFY DIFFERENCES? by

Daniel E. Heap

The purpose of this thesis was to investigate whether human resource professionals could identify job embeddedness characteristics in applicant résumés and subsequently rate the résumés with these characteristics more favorably. Participants rated the hireability of résumés via electronic survey for a specific job description. Participants also completed a self-assessment personality inventory and evaluated inferred traits on résumés to determine if there may be a similar-to-me effect in the ratings. The study consisted of 162 participants from 35 states, 95 female and 25 male with an average age of 45 and 14.8 years in the HR industry. Results indicated that HR Professionals rated résumés with more job embeddedness characteristics more favorably; however there was no support for a similar-to-me effect based on inferred personality characteristics in the résumés. These results further support the utility of the theory of job embeddedness.

Greg M. Hurtz, Ph.D.

____________________________

Date

, Committee Chair v

ACKNOWLEGEMENTS

I would like to thank the following individuals for their contribution to various aspects of this thesis: Dr. Rachel August for introducing me to the topic of Job

Embeddedness in her graduate psychology class; Dr. Chris Sablynski for providing me with unpublished materials and studies on job embeddedness; Robert Sumner for helping to provide résumé samples from the industry and for his support to finished this thesis;

Dr. Larry Meyers and Dr. Andy Job for their support and insight as readers on my thesis committee; and finally for Dr. Greg Hurtz for his invaluable and continued support as my thesis committee chair, I could not have completed this thesis without him. vi

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Chapter

Job Embeddedness Theory Development…………………………………….. 1

Job Embeddedness Dimensions……………………………………………… 4

Empirical Theory Related to Job Embeddedness……………………………. 7

Biodata as a Selection Tool…………………………………………………… 11

Empirical Support of Biodata as a Selection Tool…………………………… 14

Factors That May Affect Raters’ Evaluations of Résumés……………………

19

Factors that Affect Raters’ Evaluation That Were Not Addressed…………..

31

2. PURPOSE, DESIGN AND HYPOTHESIS OF CURRENT INVESTIGATION…. 34

3. METHOD…………………………………………………………………………. 43

Participants…………………………………………………………………… 43

Hireability Scales………………………………………………………….. 44

Résumés…………………………………………………………………… 44 vii

Page

Personality Measure……………………………………………………….. 45

Training Questionnaire……………………………………………………. 45

Procedure……………………………………………………………………… 45

Job Embeddedness Characteristics in Résumés……………………………… 48

Similar-to-me Effect………………………………………………….............. 60

5. DISCUSSION………………………………………………………………………. 69

Appendix A. Applicant Résumés…………………………………………………….. 77

Appendix B. A Brief Personality Measure…………………………………………… 82

Appendix C. Training Questionnaire………………………………………………….. 85

Appendix E. Hiring Scenario………………………………………………………… 89 viii

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

2.

3.

4.

LIST OF TABLES

Tables Page

1.

Job Embeddedness Résumé Conditions……………………………………36

Means and Standard Deviation of Résumé Hireability Question Ratings…. 49

Means and Standard Deviations of Composite Hireability Scores………… 54

Summary of Mixed Design Analysis of Variance Hireability Scores……... 55

Hireability Ratings and Personality Difference Scores……………………..64

Regression of Personality Difference on Hireability Scores: Résumé 1……65

Regression of Personality Difference on Hireability Scores: Résumé 2……66

Regression of Personality Difference on Hireability Scores: Résumé 3…... 67

Regression of Personality Difference on Hireability Scores: Résumé 4……68 ix

LIST OF FIGURES

Figures Page

1.

Marginal Means between Group 1 and Group 2………………….........

56

2.

Marginal Means of High versus Low On-the-Job……………………...... 57

3.

Marginal Means for High Versus Low Off-the-Job………………........... 58

4.

Marginal Means of High Versus Low On-the-Job within High Versus

Low Off-the-Job…………………………………………………………... 59 x

1

Chapter 1

REVIEW OF JOB EMBBEDDEDNESS LITERATURE

This study focused on the theory of job embeddedness, a construct that identifies and measures the motivational factors on and off-the-job that act as forces to bind an employee to his or her job (Mitchel, Holtom, Lee, Sablynski, & Erez, 2001). The theory encompasses a collection of influences that operates on the retention of employees, and it is these influences that cause the employee to become stuck in their jobs (Mitchell et al.,

2001). The job embeddedness construct is measured with respect to the links the employee has on-the-job and in the community, the fit of the employee in the organization and in the community, and the sacrifice that the employee would experience upon leaving the job or the community where they live. Research has shown that job embeddedness can be a valuable indicator of an employee’s tendency to quit. (Allen,

2006; Crossley, Bennett, Jex, & Burnfield, 2007; Holtom, Mitchell, & Lee, 2006; Lee,

Mitchell, Sablynski, Burton, & Holtom, 2004; Mitchell et al., 2001). Therefore, incorporating the theory of job embeddedness into the selection process can offer potential value to human resource recruiters. This context is the focus of this thesis.

Job Embeddedness Theory Development

The development of the theory of job embeddedness has drawn from several influences, including the traditional attitudinal and job alternative models of turnover,

which emphasize job satisfaction, ease of movement, and organizational commitment

(Maertz & Campion, 1998; March & Simon, 1958). With respect to job satisfaction, it is

2 most commonly referred to as the perceived desirability of movement from one job to another, where the ease of movement is conditioned upon the perception by the individual of other job alternatives. The theory of job embeddedness has also drawn from empirical research on the unfolding model of employee turnover, which emphasize paths employees follow when choosing to leave a job (Lee & Mitchell, 1994; Lee, Mitchell,

Holtom, McDaniel, & Hill, 1999). Organizational commitment has also been a focus, in addition to spill over models, organizational characteristics, and a general withdrawal construct (Cohen & Bailey, 1997; Hulin, 1991; Lee & Maurer, 1999; Marshall,

Chadwick, & Marshall, 1992). The combination of these theoretical influences has provided a valuable foundation for the development of the theory of job embeddedness.

The research conducted on the traditional models of employee turnover has been detailed in the meta-analysis of Griffeth, Hom, and Gaertner (2000). The primary focus of turnover models is withdrawal behaviors, because they offer insight into the core employee attitudes and concerns toward roles in the workplace (Hanisch & Hulin, 1991).

Although these models have the aim of addressing important organizational issues, they have had moderate to limited results in relation to explaining the reasons employees leave or stay in their jobs (Griffeth et al., 2000).

In comparison to the construct of job embeddedness, Mitchell and others (2001) provided a detailed comparison to Allen and Meyer’s (1990) three-dimensional model of

3 organizational commitment, which includes affective commitment, continuance commitment, and normative commitment. The authors outline important differences between the two constructs, in that organizational commitment encompasses only organizational characteristics, where job embeddedness encompasses organizational characteristics and non-organizational characteristics, a dimension referred to as off-thejob. Mitchell and others (2001) also draw the distinction that affective and normative commitment, or two of the three dimensional parts of the organizational commitment construct, measure different concepts than what job embeddedness measures. Affective issues are emotional ties or attachments that imply how an individual likes an organization. If an individual feels positive toward an organization, they stay for that reason. Normative commitment implies a sense of duty to the organization. Employees choose to stay due to the duty they feel to the organization. Following this logic the job embeddedness and organizational commitment constructs would be placed in separate camps. The only strong comparison between job embeddedness and Allen and Meyer’s

(1990) organizational commitment construct is the dimension of continuance commitment, which parallels the sacrifice dimension of job embeddedness. Although similarities exist, there are still major differences between the construct dimensions. For instance, job embeddedness does not include a measurement for job alternatives, and the

sacrifice dimension is community and organizational specific, therefore in comparison, can produce a more concrete measurement.

Job Embeddedness Dimensions

The job embeddedness construct consists of three dimensions. They include links such as the connections to people or activities; fit or the perceived level of similarity between an individual’s life, job and community; and sacrifice, or the difficulty with which these connections can be broken (Mitchell et al., 2001). These three dimensions

4 are measured on-the-job as well as off-the-job, and therefore creates six factors: Links-

Organization, Links-Community, Fit-Organization, Fit-Community, Sacrifice-

Organization and Sacrifice-Community (Mitchell et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2004).

The first two factors denote links, which are the connections that the individual has to his or her job, as well as the connections to his or her community. Links pertain to the degree of associations or attachment that an individual exhibits to others and or activities in their job and in the community where they reside (Mitchell et al., 2001).

Community connections include contact with neighbors, friends, community participation, churches and other off-the-job organizations that are centered in the community. These connections are important aspects of why an individual continues to live in their community. Coworkers, professional relationships, friendships and participating in work team are job influences defined as links on-the-job that address why

an individual would continue in his or her job (Maertz, Stevens & Campion, 2003;

Prestholdt, Lane, & Mathews, 1987).

Although as stated previously as being considered as a separate construct, Cohen

(1995) found that there is a complex relationship between organizational commitment and non-job related influences. The off-the-job factors have an influence on commitment at work, specifically with respect to commitment to the organization. The study found a positive correlation between organizational commitment, and three other variables:

5 importance of religious organizations, effort to religious organizations, and the importance placed upon political organizations. In addition, Cohen (1995) found that organizational support for the individual’s home life was a key variable, and concluded that individual organizations can increase positive employee attitudes by showing a more favorable stance toward these off-the-job activities. These findings lend support to the conceptual underpinnings of the job embeddedness links dimension. Leaving a job can potentially disrupt the on-and-off-the-job connections that act to keep an individual in his or her job (Mitchell et al., 2001).

The second two factors relate to the fit of the individual in the organization and the fit of the individual in the community. They are measured with respect to the employee’s perceived degree of compatibility. Job requirements, mission statement and the culture of the organization are a few of the factors individuals assess for compatibility on-the-job. According to Chan (1996), individual and organizational fit takes place when

the organizational work environment and the attributes of the person are similar and congruent. The individual attributes include beliefs, personality traits, and employee preferences, while the attributes of the organization include organizational expectations, demands, climate, norms, strategic needs, culture, and value. The dimension of fit also applies to the individual in relation to his or her community, including the culture, weather and the available activities. Fit also represents the positive forces supporting the individual’s participation in their community, and thus drawing them to stay where they

6 live and offer continued involvement.

The final two factors of job embeddedness refer to the tangible and intangible sacrifice that would be made in leaving the organization, and the sacrifice a person would make to leave the community (Mitchell et al., 2001). On-the-job sacrifice can include seniority, promotions, health benefits, retirement benefits, coworker friendships, and the costs associated with changing to a new organization. The sacrifices in the community apply more to instances when relocation is involved, however new jobs in the same region also cause sacrifices in terms of commute time, community events and ties that would not be available while working in a new job. There has been little research concerning this matter, but it is logical to think that off-the-job changes can bring significant sacrifices, and therefore can be major influences on individual actions

(Mitchell et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2004).

Empirical Theory Related to Job Embeddedness

To date, the empirical research on job embeddedness has predominantly focused

7 on theory development, antecedent identification, the prediction of behavior and the relationship job embeddedness has to other constructs (Allen, 2006; Giosan, Holtom &

Watson, 2005; Mitchell et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2004). These studies have contributed to the timely step-by-step-process of construct development and validation, just as future studies will also contribute additional value to the construct’s usefulness (Hanisch, Hulin

& Roznowski, 1998).

The results from Mitchell and others (2001) have shown that job embeddedness is significantly positively correlated to job satisfaction and organizational commitment and negatively related to job search, job alternatives, intentions to leave, and turnover. This result is intuitive considering the positive and negative relationships within the study. If an employee is satisfied in their job, one would expect them to be more embedded than someone who is not satisfied. As for the negative correlations, it is not difficult to conclude these relationships, because if an employee is not searching for a job nor have intentions to leave, they would more than likely be more embedded than someone who is looking or has intentions to leave. The findings also concluded that the job embeddedness construct provided significant prediction ability for voluntary employee turnover, a result that has offered value and credibility to the constructs utility.

In the study by Lee and others (2004), turnover was found to be negatively associated with the on and off-the-job embeddedness dimensions. When an employee leaves their job, it is safe to say that they were not embedded in their job, so a negative relationship is a believable outcome. Organizational commitment, organizational citizenship behavior, performance, and job satisfaction were all positively related to on and off-the-job embeddedness. Again, these associations are also easy to comprehend, and they seem logical, since a committed employee who performs positive behavior within the organization and is satisfied in their job, would be more embedded than an employee who was acting in an opposite manner.

Swider, Boswell and Zimmerman (2010) have shown that when employees are less embedded, had more employment alternatives and low job satisfaction, the relationship between job search behavior and turnover was stronger. The result of this situation would set the stage for an employee to leave the organization. Their findings also demonstrated that job embeddedness is a moderator in the voluntary turnover relationship and has theoretical implications that increase the value of the theory of job embeddedness. When embeddedness was high, employees who did search for other jobs had lower turnover than those who were less embedded. The application of this concept would raise the importance of having a workforce where the majority of employees were more embedded in their jobs. Developing a policy to increase employee embeddedness would be a beneficial strategy.

8

9

Ramesh and Gelfand (2010) provide international support for the job embeddedness theory. Their research has shown that job embeddedness plays a part in predicting turnover in individualistic countries like the United States, as well as collectivistic cultures such as India. This study confirms that constructs can be and should be developed and validated using cross-cultural samples and the study findings support the application of the job embeddedness construct in other cultures.

Embedded employees offer many positive outcomes to organizations, such as reducing turnover cost and increasing job knowledge through longer tenure. Considering organizations with longer tenured employees, research points to organizations having a difficult time with innovation and creativity when turnover is low (Ng & Feldman, 2010).

With longer employee tenure, the focus becomes more on the status quo keeping the work process as is, thus prohibiting environmental changes within the organization

(Warr, 1994; Wiersma & Bantel, 1992). To address this issue, Ng and Feldman (2010) investigated the relationship of job embeddedness and innovation-related behavior.

Results from this study demonstrated that job embeddedness is positively related to implementing and spreading innovation. They also found that the relationship was strongest for employees in the late-career stage and adversely weakest for employees in the early state. Employees starting their careers have more focus on learning their job and understanding the organization. These new employees have not had the tenure to become truly embedded, where those who have made it past this learning phase and are

10 embedded in their jobs, can give more of their attention, if not all attention to innovative behavior. According to Ng and Feldman (2010), these employees have job knowledge, but also have the “political savvy” (p. 1082) to implement new ideas successfully. These finding offer positive support for employers whose aim is to increase tenure within their organizations.

Giosan and others (2005) have also offered credible support for various antecedents of job embeddedness, which were positively correlated with overall embeddedness, such as the individual demographic variables of employee age and the number of child dependents in a family. Personality measures, particularly agreeableness, and conscientiousness were also positively correlated with job embeddedness. Results from Giosan and others (2005) have shown support for organizational characteristics that could be considered antecedents of the job embeddedness construct, including role ambiguity, perceived supervisor support, and participation in benefits.

External environmental factors such as transferability of skills, job investments and job alternatives have also shown that they could be antecedents to job embeddedness

(Giosan et al., 2005). The results of studies on the associated antecedents of job embeddedness may be helpful to modify the selection procedures of organizations or allow the option to modify the organizational environment to more adequately match these antecedents associated with job embeddedness. Further studies will potentially determine additional antecedents of the job embeddedness construct.

One advantage to understanding what increases employee embeddedness and therefore reducing turnover, is the costs associated with employees leaving the organization. These costs include recruiting, hiring and training new employees. Felps and colleagues (2009) developed a model that focused on turnover contagion, where it was found that job embeddedness influenced the decisions of employees in their choice to quit. Specifically, there was a negative relationship between the degree of coworker job embeddedness, and the employee’s job search behaviors. This is positive news for

11 organizations, particularly those with a highly embedded workforce. The results also emphasize the need to investigate further what develops and increases job embeddedness.

Considering the other end of the spectrum, if an organization does not have a high degree of employee embeddedness, the outcome of job search behavior may not be as optimistic.

This is one of the central purposes of this current thesis.

Biodata as a Selection Tool

In regard to selection, there are several methods commonly utilized by organizations to screen applicants for their background and experience, such as an employment application or a résumé. The information on applications and résumés are readily verifiable, inexpensive and can act to quickly reduce a large pool of applicants down to a select few who meet minimum requirements for further consideration. The information contained on an application or a résumé can be referred to as biographical data, or in short Biodata (Berry, 2003). Selection methodologies that involve biodata are

very broad, which also include the use of stand-alone biodata test designed specifically for selection in a particular company. Therefore an explanation of the practical uses,

12 details, strengths and weaknesses of biodata is warranted.

Biodata can be defined as information about an individual that is considered historical and verifiable and can be used for the selection of employees, (Asher, 1972).

Biodata can also encompass a methodology that uses systematic scoring of previous behavior to optimally predict an external criterion (Karas & West, 1999). Despite the simplistic definition, biodata has received alternative claims that there is no widely established or accepted definition for this screening technique. Along with these criticisms have come assertions that the methodology has grown too broad to also include constructs such as attitudes and individual interests into the realm of what is considered biographical data (Bliesener, 1996). These criticisms will be detailed later in other sections. Aside from this debate, employee selection procedures have successfully incorporated biographical data in one way or another for more than one hundred years

(Schoenfeldt, 1999; Stokes, 1994; Guion, 1998).

The earliest application of biographical data occurred in 1894 when T. L. Peters with the Washington Life Insurance Company in Atlanta Georgia used the method to select insurance agents (Schoenfeldt, 1999; Stokes, 1994). A weighted application blank was developed to evaluate education and work experience from standardized scores

(Berry, 2003; Schoenfeldt, 1999). This technique continued and was also used to analyze

13 responses on applications of productive and unproductive sales people (Schoenfeldt,

1999). The selection instruments eventually became known as the biographical questionnaire, which is similar to inventory items that assess personality (Guion, 1998).

The biographical questionnaire assesses specific traits by gathering and evaluating early life information about an individual, entertainment choices, goals for education, and the underlying rewards that are desired from employment (Guion, 1998).

The central assumption with regard to research in biodata is that past behavior is a predictor, or at least related to, future performance (Owens & Schoenfeldt, 1979; Schmitt,

Jenings & Toney, 1999). In addition, research also suggests that human behavior tends to be stable over time (Guion, 1991; Wernimont & Campbell, 1968). Applying these two concepts with results from experimental studies investigating biodata, and its predictive capability, there is mounting evidence supporting the practical use of biodata in the selection process (Barrick & Zimmerman, 2005; Cole, Feild, Giles, & Harris, 2004;

Griffeth et al., 2000; Harvey-Cook & Taffler, 2000; Karas & West, 1999; McManus &

Ferguson, 2003; Robertson & Smith, 2001; Schmitt et al., 1999; Schoenfeldt, 1999;

Stokes, Toth, Searcy, Stroupe, & Carter, 1999; West & Karas, 1999).

According to Robertson and Smith (2001), biodata on employment applications, résumés, and curriculum vitae are second in popularity to interviews as a method of selection because they allow prospective employees to communicate their qualifications and background to future employers. Although organizations frequently gather

14 knowledge about an individual using biodata, the method is often not used to its full potential, particularly in regard to the pre-selection process (Harvey-Cook & Taffler,

2000). Berry (2003) refers to selection as a group of actions that employers can use to accumulate information about prospective employees and then subsequently use that knowledge to decide whom to hire. Although there are multiple procedures available for the selection of employees, this study specifically focused on biographical data collected from employee résumés.

Empirical Support of Biodata as a Selection Tool

The development of biodata measures continued in the 1920’s, followed by extensive use as a selection tool during World War II by the United States military

(Guion, 1998). Schoenfeldt (1999) cites biographical items that predicted the success of student pilots and navigators in the Air Force. Parish and Drucker (1957) employed biodata items as the most successful method to predict officer leadership ratings from their peers in officer candidate school (Schoenfeldt, 1999).

William Owen and his students at the University of Georgia have become a major factor in the support of biographical data as a method of selection (Guion, 1998). In support of this method’s utility, Harvey-Cook and Taffler (2000) reference several studies that show life histories can contain satisfactory reliable evidence to allow employers, and others the ability to make truthful predictions of future job performance.

As an example, in the summary of personnel selection by Robertson and Smith (2001),

15 they mention that biodata has been used in the selection of employees across numerous occupations including private sector clerical jobs (Mount, Witt, & Barrick, 2000), in the accounting field (Harvey-Cook & Taffler, 2000), mechanical equipment distributors

(Stokes & Searcy, 1999), hotel staff (Allworth & Hesketh, 1999), civil servants (West &

Karas, 1999), managers (Wilkinson, 1997), and naval ratings (Strickler & Rock, 1998).

The study by Wilkinson (1997) employed biodata models to predict vocation interest as defined by Holland’s Self Directed Search (Holland, 1985) of a group of potential managers. Although vocational interested does not equate to vocational ability, this research along with other studies referenced by Wilkinson (1997) show the versatile utility of biographical selection measures (Eberhardt & Muchinsky, 1984; Mumford &

Owens, 1982; Owens & Schoenfeldt, 1979).

As an endorsement and warning, Snell, Sydell, and Lueke (1999) point out that biodata is a non-cognitive procedure with two sides to the outcome. Biodata measures dispositions while at the same time avoids the adverse impact of cognitive ability tests.

On the other hand, the simplicity of biodata items are often easy to guess. Although Snell and others (1999) emphasize the positive and negative side of non-cognitive measures; they claim biodata methods are foretelling and the increased predictability does not come without a cost since applicants can often tend to guess the desired response (Hunter &

Hunter, 1984; Reilly & Chao, 1982).

16

In some respects, biodata can be viewed as restrictive compared to cognitive tests since they are generally developed for a single organization and generalizing to other companies is challenging (Harvey-Cook & Taffler, 2000). In other instances, research has found that biodata measures do have generalizability to other jobs and organizations and can be used by more than one organization (Rothstein, Schmidt, Erwin, Owens, &

Sparks, 1990; Wilkinson, 1997).

Biodata measures used in selection have shown to have validity evidence in experimental studies in regard to the prediction of job performance ratings and productivity (Brown, 1981; Mumford & Stokes, 1992; Reilly & Chao, 1982; Schmidt,

Hunter & Caplan, 1981; Schmidt, Gooding, Noe, & Kirsch, 1984). Biodata selection measures have also validity evidence for tenure, training, sales success and performance

(Hunter & Hunter, 1984; Reilly & Chao, 1982; Schmitt et al., 1984).

Studies by Harvey-Cook and Taffler (2000) have produced evidence with respect to the use of a biodata approach to select entry level accounting professionals. Mael and

Ashforth (1995) have produced validity evidence for person-organization fit elements that pertain to individual disposition, group attachment and pursuits of achievement.

Validities of biodata sources have been shown to range from .30 to .40 (Hunter & Hunter,

1984; Reilly & Chao, 1982; Schmidt & Hunter, 1998) and by using predictive models during the selection process the reliability and validity can significantly increase

(Bliesener, 1996; Harvey-Cook & Taffler, 2000). The meta-analysis of Bliesener (1996)

17 affirms the validity of biographical inventory techniques, with a sample size weighted mean validity of r = 0.303

, however, Robertson and Smith (2001) report results indicating that concurrent validity of biodata studies were higher r = 0.35.

With respect to biodata development procedures and scale validities, there is increasing importance placed on the biodata characteristic and content area (Mael, 1991).

First, biographical data has been theoretically premised within an ecology model (Mael,

1991; Mumford & Stokes, 1994; Mumford & Owens, 1987). This model includes the differences of individuals that can be attributed to resources obtained from their heredity and environment. In addition, it includes the specific changes from cognition and learning that are made by each person to adapt to individual situations. A driving force for each individual is the expected reinforcement that will be obtained through the selection situations. These situations are based on the perceived values and needs that reflect preexisting individual characteristics. Mael frames this aspect clearly with reference to a framework based on how an individual believes in him or herself and the world, and how they feel it should proceed.

Developing the ecology model further, once individuals make choices to obtain goals and desires, additional adaptation is needed, followed by more choices. This process has a specific intent to continue the satisfaction of individual values and needs.

The repetitive behavior process and choices form a pattern that subsequently becomes the foundation of performance prediction (Mael, 1991).

To address the prediction of performance, biodata items have defined attributes and are proposed to fall into three overarching categories: Historical, procedural

18 boundaries, and legality and morality issues (Mael, 1991). The historical category encompasses items of the past, which lays a foundation for all biographical information.

Procedural boundaries frame the past by suggesting that items are external, objective, based on first-hand experience, have discrete responses and are ultimately verifiable.

Lastly, items should be legal and moral in regard to selection issues so that they are controllable, have equality, are relevant to the job and include properties that lack personal invasions.

Success, failure, profit or loss for any corporation is a result of overall effort. In this vein, research focused on increasing job embeddedness can be a valuable asset to the overall organization. Organizations depend on employees to produce products or provide services and therefore the process of employee selection is a critical task. Empirical studies have shown positive utility for incorporating biodata contained on résumés during the selection process. One particular study demonstrated job recruiters’ abilities to draw personality inferences taken from résumé biodata (Cole et al., 2004).

Biodata has also been shown to predict high performance of sales people as well as identifying those who will remain in their jobs (Gable, Hollon & Dangello, 1992).

Investigating the theory of job embeddedness within the context of biodata is a central theme to this study by tasking human resource professional to rate the hireability of

19 applicants by reviewing résumés that contain job embeddedness characteristics. Although this method offers potential value to the employee selection process, an investigation into the possible challenges created by this task is merited.

Factors That May Affect Raters’ Evaluations of Résumés

Résumé screening is used more frequently than the personal interview in selection, and research has shown that evaluations provided by screeners are predictive of employer job offers (Cable & Judge, 1997). Considering the popularity of screening and the predictive ability, there are number of factors that affect rater’s evaluation of employee résumés. The most obvious factor is that the process gives the résumé screener an enormous amount of control over the selection process. Screeners serve as keeper of the organizational gate, and ultimately decide which job applicants will be turned away, and which applicants will be considered worthy of an interview (Cole, Feild & Stafford,

2005).

Compounding the factor of the control screeners have over applicants, is the premise that recruiters often infer psychological attributes, like personality, ability and interests from résumés. The inferences are due to the belief that the information on the résumé is associated with job appropriate attributions that are important for job success

(Cole, Field & Giles, 2003; Rubin, Bommer, & Baldwin, 2002). Studies have found that résumé biodata is significantly correlated with personality and disposition and the inferences screeners make impact their decision about the applicant’s employability in a

20 specific organization (Brown & Campion, 1994; Cole et al., 2004). Although the goal is to reduce the applicant pool, if the inferences screeners make are inaccurate, they will make mistakes and therefore introduce what scientist call error into the evaluation process. This error ultimately in the end, affects the applicant pool. In this light, the importance of HR professional’s screening task becomes particularly imperative

(Dipboye & Jackson, 1999).

The study by Cole and others (2005) was designed to investigate the inferences that reviewers make of applicant personalities based on biodata in the résumés.

Participants in this study were tasked with reviewing a résumé in the context of a specific job description, and then asked to judge the information on the résumé using an adjective rating scale to assess the personality of the individual. The rating scores of the reviewers were then correlated with self-report personality scores provided from the applicant.

Results indicated that the reviewers accurately inferred two personality traits, openness to experience ( r = .33, p < .01) and conscientiousness ( r = .33, p < .01). The study by Cole and others (2005) also included a 45 minute training exercise as a condition and the results found that the validity coefficients increased substantially for extraversion and conscientiousness after the training. The coefficients were also significantly positively correlated with the applicants self-report personality assessment. Although the neuroticism coefficient changed the most before and after training, from a negative coefficient to a positive coefficient, it was not determined to be significant. These results

21 support the ability of screeners to accurately infer personality traits, but they also support the utility of training excises for HR professionals to help assist in the accurate selection of employees.

This present study further investigated the utility of training in the process. The goal was to increase the knowledge of what to look for while screening a résumé and also increase the valid inferences made by the screener. The personality testing research is extensive with respect to studies about selection; however results are mixed concerning the validity of personality testing in job selection. The results are mixed mostly when taking into account the research that was conducted before and after solidifying the big five framework (Barrick & Mount, 1991; Barrick & Mount, 1995; Guion & Gottier,

1965; Hogan & Ones, 1997; Hurtz & Donovan, 2000; Schmitt et al., 1984; Tett, Jackson

& Rothstein, 1991).

Although this current study will not investigate the relationship between personality and job performance, a thorough understanding of the literature will shed light on the association of personality in selection and the personality inferences that are made by résumé screeners. According to Murphy and Dzieweczynski (2005), there are three factors that have influenced increased confidence in personality testing. First, is the increasing reception of the five-factor model of personality, which has set a firm framework around the measured traits. Second, several meta-analysis studies have found a small, yet consistent association between personality and job performance. The third

reason for the increase in confidence has been the positive developments in the measurement of personality (Barrick & Mount, 1991; Hurtz & Donovan, 2000; Kanfer,

22

Ackerman, Murtha, & Goff, 1995; Tett, Jackson, & Rothstein, 1991).

In reaction to these developments, personality research has become more active, yet the topic of testing in personnel selection continues to be controversial. One such controversy surrounds the idea that applicants describe their personalities in socially appropriate ways when they feel that important decisions will be made using personality inventories (Murphy & Dzieweczynski, 2005). There are also studies that support the ability of applicants to inflate scores by faking personality tests. To the contrary, there’s additional research supporting the development of personality tests that can discourage faking (Ellingson, Smith, & Sackett, 2001; Hough, Eaton, Dunnette, Kamp, & McCloy,

1991; Ones, Viswesvaran, & Reiss, 1996; Rosse, Stecher, Miller, & Levin, 1998; Schmit

& Ryan, 1993; Zickar & Robie, 1999). Considering these factors, research is moving more toward a focus on the relevance of personality in selection, rather than the prediction of job performance (Murphy & Dzieweczynski, 2005). This was the focus of this study, predominantly since one of the job embeddedness dimensions pertains to fit, and therefore personality in this context is very relevant. The fit of the individual on-thejob and the fit of the individual off-the-job play an important part in the degree to which they are embedded in their job and their community. Therefore it is reasonable to conclude that individual personality was an aspect in this investigation.

23

In regard to personality on-the-job, research has shown that managers put emphasis on personality characteristics when making hiring decisions just as heavily as they do for an applicant’s general mental ability (Dunn, Mount, Barrick, & Ones, 1995).

The task of hiring an individual that will make a positive contribution, and also have a productive influence on the organization is important for overall group success. Although controversial in nature, employees can easily complete daily tasks, but if their personality characteristics are challenging to coworkers, the outcome of hiring them can be less than ideal (Barrick & Mount, 2005).

The links that have been made between personality constructs and job performance, have revealed that conscientiousness and emotional stability, two of the Big

Five traits, generalize in the prediction of overall performance (Barrick, Mount, & Judge,

2001; Hogan & Holland, 2003; Hurtz & Donovan, 2000; Judge, Bono, Ilies, & Gerhardt,

2002; Judge & Ilies, 2002). Conscientiousness applies to exerting effort and willingness to follow rules, while emotional stability refers to the ability to allot resources to accomplish tasks. These two predictors have been found to generalizable across situations and can be looked upon as measures that affect performance in all jobs, just as general mental ability affects all job performance through can do capabilities (Barrick & Mount,

2005; Hurtz & Donovan, 2000; Schmidt & Hunter, 1998).

Openness to experience, extraversion, and agreeableness, have been shown to be valid predictors of performance, but only in specific positions or situations. These

positions and situations include jobs that require status, significant interactions with others, power, or influence. In these cases, extraversion has been found to be related to

24 job performance because of the need to be ambitious, socially centered, assertive, and energetic (Barrick et al., 2001; Hurtz & Donovan, 2000).

Agreeableness was an important predictor for jobs that needed interactions with others, particularly teamwork or mentoring situations. When it comes to working in teams, agreeableness was the single best predictor of job performance (Mount, Barrick &

Stewart, 1998). Logically, it is clear to understand that an employee who is disagreeable, stubborn and insensitive, all characteristics that describe someone low in agreeableness, would not be as effective in a team environment.

Lastly, the personality trait of openness to experience has been found to influence the individual ability to adapt to change and be creative. When individuals are open to experience, as an employee in a corporation, they tend to be better equipped to deal with change. Dealing with change is easier because they have refined characteristics such as sensitivity, inquisitiveness, and autonomy (George & Zhou, 2001).

Hogan and Holland (2003) present evidence that supports the benefits of matching criteria that are relevant to specific personality traits, because when it comes to predicting the ability to get along, agreeableness, emotional stability and conscientiousness were the best predictors, whereas when getting ahead was the criteria,

25 the best personality predictors were extraversion, conscientiousness and emotional stability.

Although the investigation of individual personality traits has value, there should be greater emphasis placed upon the investigation of the entire personality of an individual, particularly if the interest is to determine how well personality predicts an outcome (Barrick & Mount, 2005). As an example, using all of the Big Five factors for predicting overall job satisfaction, the reported multiple correlation was .41 (Judge,

Heller, & Mount, 2002). Judge and others, (2002) was able to predict the emergence of leadership, and the multiple correlation using a composite of the Big Five was .53, whereas it was .48 over effectiveness and leader emergence. The research literature is prolific with respect to results indicating the benefit of using all the personality traits as a composite to predict performance. As added value, the mean score differences between racial and ethnic groups in personality testing are small to nonexistent, which helps in hiring a diverse workforce. Cognitive ability test produce differences that have been known to cause issues such as employment discrimination lawsuits (Hough, 1998;

Hough, Oswald, & Ployhart, 2001; Mount & Barrick, 1995).

As stated earlier, personality testing is not the focus of this study, but a thorough understanding of the topic is important for employee selection. Particularly since résumé screening and the potential to infer personality characteristics is a potential outcome in the selection process. If references are made, recruiters and HR professionals should be

26 aware of the implications and develop strict standards as an organization to deal with the consequences or minimize the adverse outcomes.

Another factor that can influence the raters evaluations of résumés is the potential introduction of the similar-to-me effect, which refers to the model presented by Schneider

(1987) as the attraction, selection, attrition model, or in short ASA. This model proposes that individuals are attracted to and also selected by organizations with respect to their individual characteristics and how well they are suited to the structure and culture of the organization. Individuals who are not similar to the organization do not tend to stay in their job or these individuals are not selected in the first place. The process eventually leads to a group of employees who tend to become homogeneous in specific personality dimensions. This homogeneous workforce in the long run influences the organizational work process and structure.

The central emphasis of the ASA notion is that it is the people in the organization that determine organizational behavior, and not the external environment or the situation.

The collective personality of the individuals, become the culture, processes and structure and this is one of the main reasons that one organization is different from one another organization. Weekley and Baughman (2006) define the ASA framework in the following way. Attraction is the fit of a person’s characteristics, interests and personality to the organizations characteristics and climate. Selection is contingent upon how the

27 two meets each other’s needs. Attrition on the other hand occurs when people leave organizations that they do not fit.

The ASA framework is also referred to as the homogeneity hypothesis, because individuals or members of the same organization should be more alike in collective personality than members of different organizations. Schneider’s (1987) research showed that a company founder or executive determines process and organizational structure, which sets the tone for the attraction of like individuals.

Prior to Schneider, Miller and colleagues had investigated the relationship between the Chief Executive Officer and the structure and strategy of the company

(Miller & Droge, 1986; Miller, Kets de Vries, & Toulouse, 1982). Personality, attitudes and values are the major focus on the ASA framework; therefore it seems reasonable to conclude that there is merit to a top down creation of organizational personality. This premise is supported by organizational culture theorists who propose that the founders start the homogeneity of the organization by their leadership and their characteristics that they embed into the organization. The organizational similarity is continued by choosing others who are very similar to themselves (Schein, 1992).

In addition, evidence exists that organizations are similar in terms of their manager’s personalities. These managers are linked to upper management and also are connected to the employees they supervise (Schneider, Smith, Taylor & Fleenor, 1998).

The connection to the homogeneity hypothesis in this light is not difficult to recognize.

In vocational psychology, attraction applies to the individual interests and personality that attracts a person to a career. Most notably, this concept was defined by

28

Holland (1985), where he proposes that careers are divided into six major types:

Intellectual, artistic, social, enterprising, conventional, and realistic. The atmospheres of careers are generally similar to the people who join them. Therefore the selection process is restricted by the environment of the organization that requires specific competencies.

These competencies in demand for jobs are then filled by individuals whose skills make up with these competencies, and thus in the end the business restricts the type of individuals in the organization based on selection needs (Campbell & Hansen, 1985). The attrition phase as defined earlier again refers to the individuals who do not fit, and their tendency to leave the organization.

Giberson, Resick and Dickson (2005) investigated two relationships. First they looked at the relationship between organizational trait homogeneity through examining the personality traits and personal values similarities of members within the organization.

Secondly they looked at the relationship between the personal characteristics of top leaders and the personality and values profiles of their organizations. Results supported the homogeneity of organizational hypothesis in that there was found to be a great deal of agreement in personality and values in organizational membership and that these traits in the organization did differentiate one group from another.

29

Stevens and Szmerekovsky (2010) presented the concept of selection not only in terms of organizational characteristics, but in regard to the recruitment methods employed. One way potential employees learn of job possibilities is through advertisements in the media. The wording of the advertisement is often symbolic of the type of employee the organization seeks to hire. Using descriptive ads as a recruitment method presents organizations with time savings strategies by attracting employees who would most likely fit in and therefore screen out those who do not fit in. Results from their study supported this strategy.

Combining theory of vocational choice and the ASA homogeneity of personality theory, the study by Satterwhite, Fleenor, Braddy, Feldman and Hoopes (2009) investigated the link between similar personalities within organizations, and the link between similarities in personalities in particular occupations. This goal of this particular study was to widen the focus of the similar-to-me research that would have a lot of potential applications. The results of this study supported the homogeneity hypothesis within occupations as well as with in organizations, however the homogeneity was stronger with in occupations than within the organization. It appears that career choice is driven by similarity in personality more than the similarity in the individuals in the organization. Having this knowledge can be helpful in résumé screening to look for occupation similarities in job history, in addition to making sure that this history matches with the occupation category of the job description.

30

Although the present study focused solely on résumé screening, previous research has been conducted on the similar-to-me effect that occurs during employment interviews

(Sears & Rowe, 2003). Through prescreening participants, the authors were able to separate out and use only those participants who scored low or who high in conscientiousness. These particular participants were tasked to review résumés and watch interviews of applicants. The participants were also asked to rate interviewees on a competency model, four outcome variables (e.g. job suitability, perceived similarity, perceived competence and their affect toward the applicant) and the big five personality dimensions. The results indicated that there was a significant similar-to-me effect in the judgment of overall job suitability, and competence ratings. It was interesting to note that the effect only occurred for raters that were high in conscientiousness; while raters low in conscientiousness did not rate differences between interviewees.

These results are contrary to the conventional thought process that high conscientious raters would rate those they rated as high more favorably, while low conscientious raters would rate those low more favorable. In this case, although the low conscientious rater and interviewee were similar in characteristics, they did not recommend them for a job that required a conscientious person, which may imply that similar-to-me only applies when the similarity is a non-job related construct. Based on the research presented, there are a number of factors that affect raters’ evaluation of

résumés. In addition to these factors, there are also a number of other factors that affect ratings that this study did not address.

31

Factors That Affect Raters’ Evaluations That Were Not Addressed

This study did not address a number of other factors that affect raters’ evaluations of résumés. One such factor is gender discrimination. The first name on a résumé often denotes the gender of the individual, so if a rater is preferential to one gender over the other, the rating of the individual can be influenced in a positive way or a negative way.

Another factor that can influence the ratings of résumés is ethnicity. Applicants with an unusual last name or appear to be of an origin from another country, in many cases, but not always can be an indication of another race or at least denote someone who may be a minority. The name can also provide information that would imply individual differences separating them from the rest of the applicant pool. If a rater allows this information to influence them, the result can be detrimental. This influential aspect was controlled for in this experiment.

Age discrimination can also be another factor that can affect ratings if résumé screeners assume age by the year the applicant graduated from college. Again if there is a preference for a specific age category, then there can be adverse ratings for those individuals.

Other factors that may influence raters’ evaluations are résumés that are poorly formatted, have spelling errors, or contain information that is not correct. An additional

32 topic that has come to light over the past year or more is those individuals who are currently unemployed, and have been for a long period of time. This situation complicates the application process for these individuals and there has been several media references addressing this topic. Although there are a number of important potential influences that can effect raters’ evaluations, they are all factors that this study did not address. Therefore, a valiant effort was be made to control for these variables as much as possible.

The controls for this study was accomplished by using a generic name, such as applicant one, by not including college graduation dates and by ensuring that all résumés were formatted similarly, with similar content as to make the comparison based on job embeddedness factors instead of individual differences factors. Although these factors may have an influence to raters’ evaluations of résumés, they should be addressed more specifically in future studies.

In summary, this study addressed important aspects of employee selection, by focusing on the employment résumé screening process. Through the screening process this study determined the ability of HR professionals to identify job embeddedness characteristics and subsequently rate résumés with a higher degree of job embeddedness factors more favorably, than résumés that had a lower degree of job embeddedness factors. This study also sought to identify if there was a similar-to-me effect in the

screening process and addressed how useful training would be for those involved in selection.

33

34

Chapter 2

PURPOSE, DESIGN AND HYPOTHESES OF CURRENT INVESTIGATION

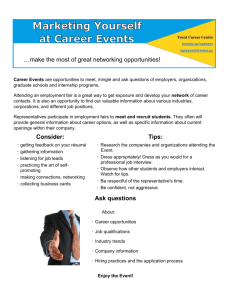

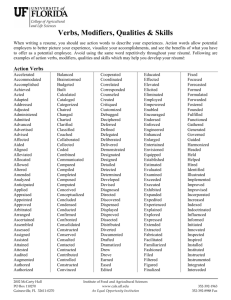

The purpose of this study was to explore whether human resource professionals would rate applicant résumés more favorable when a higher degree of job embeddedness characteristics were included on a résumé, than when a lower degree of job embeddedness characteristics were on a résumé. On-the-job embeddedness characteristics included: Working in the same industry as the job opening, previous supervisory experience, volunteer committee membership and long job tenure in the résumé job history. Off-the-job embeddedness characteristics included the following:

Currently live in the same city as the job opening, attended college in the same area, home ownership and community volunteer such as PTA president (see Table 1).

The study consisted of a 2 (high on-the-job embeddedness vs. low on-the-job embeddedness) x 2 (high off-the-job embeddedness vs. low off-the-job embeddedness) x

2 (rate résumés before training questionnaire vs. rate résumés after training questionnaire) mixed factorial experimental design, where the first two factors are within-subjects and the third factor is between-subjects. The experimental design tested the hypothesis that résumés with a higher number of job embeddedness characteristics on and off-the job would be rated higher for hiring than those with a lower number of on and off-the-job characteristics. The hireability rating in this context referred to a measure that determined

35 the likelihood that the human resource professional would interview and hire the applicant. In addition, this study investigated two additional facets; the first was to determine if the favorability of the ratings from the human resource professionals were associated to a similar-to-me effect from inferred personality characteristics as measured by the Big Five in the résumés. In other words, if human resource professionals perceive the applicant to be similar to themselves with respect to personality, do they rate the résumé more favorably than those they perceived to be more different from themselves?

Secondly, this study explored the potential application of a suggestive training questionnaire to assist in guiding the human resource professionals in résumé screening and assess the degree to which the job embeddedness characteristics were of interest in screening applicants. The training questionnaire also allowed the assessment of how it could affect the favorability rating of the participants.

Table 1

Job Embeddedness Résumé Conditions

High on-the-job

High off-the-job

High on-the-job

Low off-the-job

Low on-the-job

High off-the-job

Low on-the-job

Low off-the-job

Résumé 1 Résumé 2 Résumé 3 Résumé 4

Address Portland

House /

Apartment

House

Texas

Apartment

Portland

House

Georgia

Apartment

Education Portland-MBA

Portland–B.S

Experience

Portland, OR

Portland, OR

Portland, OR

Denver–MBA

Texas–BBA

Irving, TX

Tulsa, OK

Houston, TX

Portland–MSF

Portland – B.A

Kennesaw-MBA

Norfolk–B.S

Portland, OR

Portland, OR

Portland, OR

Atlanta, GA

Blue Bell, PA

Griffin, GA

Norfolk, VA

Job Title Audit Mgr.

Sr. Auditor

Sr. Auditor

Sr. Auditor

Sr. Auditor

Sr. Auditor

Sr. Auditor

Accountant

Audit Assoc.

Audit Assoc.

Sr. Auditor

Controller

Business Mgr.

Supply Officer

Volunteer Yes –work

Yes–personal

Yes – work

Yes – personal

Yes – Personal None

36

Research has pointed to biographical data as an accurate means to predict future performance (Owens & Schoenfeldt, 1979; Schmitt, Jennings & Toney, 1999). In

37 addition, research also suggests that human behavior tends to be stable over time (Guion,

1991; Wernimont & Campbell, 1968). These two concepts, combined with the empirical biodata studies, offered supportive evidence for the practical use of résumés in this study

(Barrick & Zimmerman, 2005; Cole, Field, Giles, & Harris, 2004; Griffeth et al., 2000;

Harvey-Cook & Taffler, 2000; Karas & West, 1999; McManus & Ferguson, 2003;

Robertson & Smith, 2001; Schoenfeldt, 1999; Stokes, Toth, Searcy, Stroupe, & Carter,

1999; West & Karas, 1999).

The study was designed to test hypotheses addressing the accurate identification of job embeddedness factors contained in résumés. Four résumés reproduced in Appendix

A were presented to participants that either had a high level of job embeddedness characteristics or they contained a low level of job embeddedness characteristics. A hypothetical company and employment position description was provided along with the applicant résumés to create the scenario in which to rate the hireability of applicants.

Instructions to participants were to read the hypothetical hiring description, then review and rate the résumés within that context.

The human resource professionals were also asked to rate the perceived personality characteristics contained in the résumés, in addition to completing a selfassessment using the ten-item personality inventory (Gosling, Rentfrow & Swan, 2003).

38

Studies have shown the ability of recruiters and human resource professionals to infer personality characteristics from paper résumés (Kirkwood & Ralston, 1999). A comparison of how they rated the applicant versus how they rated themselves was investigated to determine if there was a similar-to-me effect in the rating methodology of the résumés.

The last task that participants completed was a general questionnaire that was devised to investigate what aspects are important to the participants as they screen résumés. The questionnaire also investigated the degree to which job embeddedness characteristics were used in evaluating résumés. This aspect of the study helped to show the importance of properly screening résumés and what could be influenced to obtain a more accurate outcome. All participants evaluated and rated the same résumés; however the order of the tasks varied as the participant were randomly assigned to one of two groups.

To address experimental realism, résumés were used from individuals employed in the industry of focus. The names of the applicants were removed and the format of the résumés was identical. Modification to the résumé matched the specific conditions of the study by enhancing or lessening the degree to which off-the-job embeddedness and or onthe-job embeddedness factors were present on the résumé. Each of these items was taken from factors identified in the job embeddedness theory.

39

Current research has put forth that the job embeddedness construct can explain variance not identified in turnover models and thus more accurately predict employee turnover. Investigating the potential that professionals would be able to identify and subsequently rate applicant résumés with job embeddedness factors more favorably lends support to the construct. Although exploratory in nature, the potential positive outcome can add empirical evidence to the selection screening process and therefore eventually increase employee job embeddedness through effective selection over a period of time.

To date, experimental evidence has shown that job embeddedness is measured through a 31-item questionnaire administered to employees. Higher scores from the measure indicated the employee was more embedded in his or her job. Lower scores meant the employee was less embedded in his or her job. The goal of this study was to determine if the presence of embeddedness characteristics would be identified implicitly or explicitly from résumés, and then evaluate whether the ratings from the human resource professionals were more favorable when the characteristics were present versus when not present. Therefore, it will be hypothesized that:

H

1

: Human resource professionals would rate the résumés that contain a higher number of job embeddedness characteristics with more favorable hireability ratings than résumés that contain a lower number of job embeddedness characteristics.

40

The fit of the employee to the organizational is a crucial aspect of employee embeddedness. Individuals who have knowledge, skills and ability that match the organization and their job are more capable of completing the daily tasks and have the ability to work more effectively within the organization. With respect to this point, human resource professionals would also be able to rate résumés with job embeddedness characteristics such that:

H

2

: Applicant résumés that contain perceived personality characteristics similar to the résumé reviewer would be rated higher than the résumés of those perceived to be different.

Community activities reported on a résumé and a job history with a long tenure in the same town are a very good indicator someone who has strong links to a community.

Applicants who have a local presence in the community for a longer period of time, list hobbies, accomplishments or volunteer work on applications provide greater insight into their off-the-job activities. These activities increase the degree of links that the applicant has when not at work, versus an employee who does not have any off-the-job hobbies or accomplishments listed on their résumé. Therefore, human resource professionals will rate résumés with off-the-job embeddedness characteristics such that:

41

H

3

: Applicant résumés that contain a higher number of off-the-job embeddedness characteristics would be rated higher than résumés that contain lower number off-the-job embeddedness characteristics.

In addition to the hypotheses that HR professionals would rate résumés more favorably with job embeddedness characteristics, and those that are perceived to be similar to them, this study investigated if the order the participant completes the task of the experiment have an effect on the ratings of each résumé. The design studied the ratings of the participants grouped together to determine if the ratings differed based on the order of the experiment tasks. For instance, offering training to HR professionals may potentially impact the ability to more effectively screen résumés during the hiring process. Therefore, this study explored the difference between groups of participants who reviewed the résumés and then immediately were tasked to rate the hireability of applicants before completing other experimental tasks. The other group of participants reviewed the résumés and then completed additional tasks before they rated the hireability of the applicant. Based on this premise, it was hypothesized that:

H

4

: Participants who complete all of the experimental tasks prior to completing the hireability ratings would rate résumés more consistently than the groups that were tasked to rate the hireability first and then complete the other tasks.

In conclusion, this study’s aim was to offer organizational value through formulating usable strategies that human resource professional can deploy in screening résumés and lend credence to the job embeddedness construct. The study also potentially offered support to provide training to better assist in the planning, recruitment and selection of employees. This strategy possibly can increase employee tenure and decrease voluntary turnover through improved selection techniques.

42

43

Chapter 3

METHOD

Participants

Participants for this study were 162 human resource professionals who review, screen, and conduct employee selection activities as part of their daily job tasks. After removing incomplete survey responses, there were a total of 134 participants (83%) who completed all the survey questions.

To gather a realistic sample of participants from a variety of companies across the

United States, participants were recruited via email from organizations such as the

Society of Human Resource Management, the Society of Industrial Organizational

Psychology, and other referral sources with connections to HR departments across the

United States. Demographic information was provided by 95 females (79%) and 25 males in the sample. Human Resource departments have a large female population and therefore the high female participation was not surprising. Participants came from 35 states throughout the United States, with the highest participation coming from Oregon

(17), Colorado (14), California (8), Pennsylvania (8), and Florida (7).

Average age of the participants was 45. The youngest participant was 24 years old and the oldest participant was 64 years old. The average tenure on-the-job was 14.8 years; however the range was from 1 to 40 years of experience. Participants were asked

44 to provide their job title and industry of employment. The most common job titles, adjusted for similarity from company to company were: Human Resource Manager (37),

Director of Human Resources (28), Human Resource Generalist (17), and Consultant

(12).Thirty-seven broad industry categories were represented in the sample and the most prevalent industries were Government (12), Health Care (12), Manufacturing (12),

Financial Services/Banking (7), Education (6) and Non Profit (6).

Materials

Hireability Scale

Hireability was measured using a three-item, 7-point hireability scale that was adapted from Rudman and Glick (2001; α = .91). Items include “I would interview this applicant for an entry-level management position”; “I would consider hiring this applicant for an entry-level management position”; and “I would personally hire this applicant for an entry-level management position.”

Résumés

HR Professionals reviewed each of the four employee résumés manipulated to match one of four conditions. The first résumé included high levels of on-the-job and offthe-job embeddedness factors. The second résumé included high levels of on-the-job embeddedness factors and low levels of off-the-job factors. The third résumé included low levels of on-the-job embeddedness factors and high levels of off-the-job factors. The

fourth résumé contained low levels of both job embeddedness factors. The résumés for each condition are reproduced in Appendix A.

45

Personality Measure

To assess the perceptions of applicant personality characteristics, the ten-item personality inventory (TIPI) developed by Gosling, Rentfro, and Swann (2003) was used.

The TIPI is a brief personality inventory consisting of ten pairs of adjectives corresponding to the Big Five personality traits and the rating is based on a 7-point scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. After rating the inferred résumé personality traits, participants also rated the extent the paired words applied to them individually. The inventory is reproduced in Appendix B.

Training Questionnaire

A 10-item questionnaire reproduced in Appendix C evaluated the extent that the participants evaluated and subsequently rated the hireability of the applicants based on job embeddedness characteristics. This questionnaire also served as a manipulation to assess the difference in the ratings between the two groups, as one group rated the résumés before they complete this questionnaire, and one group rated the résumés after they complete this questionnaire.

Procedure

Each participant completed an online survey consisting of four measures and demographic information with the objective of evaluating the hireability of four résumés

46 for a job position in Portland, Oregon. Participants who agree to take part in the study were provided a link to access the study and were asked to agree to informed consent. HR professionals were told the purpose of the study was to examine differences in employee selection and evaluation criteria and would take less than 30 minutes of their time. A jobhiring scenario was presented for a specific city, industry and a job title to set the stage for this hypothetical situation. Each participant evaluated the same four résumés that contained varying levels of on and off-the-job embeddedness characteristics. The résumés of focus were the ones that included high on and off-the-job and low on and offthe-job levels of job embeddedness characteristics. The two other résumés with a mix of high and low levels of job embeddedness characteristics still provided insights.

Participants were divided into two groups based on the order of response and the first group had the task to read the job description scenario and then evaluate each résumé, rating the résumé using the hireability scale previously described. The participants then also assessed the perceptions of applicant personality characteristics using the ten-item personality inventory, followed by the human resource professionals completing the training/job embeddedness questionnaire to assess the extent that their hireability ratings were based on job embeddedness characteristics contained in the résumés. Finally each participant also used the same inventory to assess his or her own personality characteristic. The second group started with the training questionnaire, assessed their

47 own personality using the TIPI, reviewed the résumés, rated the résumés, and finally assessed the personality of the applicant using the TIPI.

Assigning participants to one of two groups assessed the degree to which the human resource professional’s hireability ratings could be manipulated by increasing training in screening résumés. Participants were randomly assigned to the two experimental conditions based on email response order of odd and even numbers.

Additionally, one group of participants completed the training questionnaire and their own personality assessment before they reviewed the résumés to more accurately control the experimental conditions. At the conclusion of the study, and exiting the survey, participants were debriefed and notified of the purpose of this study, with contact information to obtain answers to any specific questions.

48

Chapter 4

RESULTS

Job Embeddedness Characteristics in Résumés

The primary purpose of this study was to explore whether Human Resource professionals would rate applicant résumés more favorably when a higher number of job embeddedness characteristics were included on a résumé, than when a lower number of job embeddedness characteristics were included. Each résumé was rated on a 7-point rating scale by the HR Professional on whether they would consider interviewing, consider hiring, or personally hire the applicant. Table 2 displays the means and standard deviations for each hireability question and the sample size. From a high level overview, high on-the-job and low off-the-job (résumé 2) was rated with the highest hireability ratings, followed by high on-the-job and high off-the-job (résumé 1) and then low on-thejob and low off-the-job (résumé 4). The lowest hireability ratings were given to the condition of low on-the-job and high off-the-job (résumé 3). With respect to variability in the standard deviation of the hireability ratings, résumé three had the highest standard deviation of all four résumés, while résumé two received one of the lowest.

49

Table 2

Means and Standard Deviation of Résumé Hireability Question Ratings

Interview Consider Hiring Hire Applicant

On JE Off JE n M SD M SD M SD

Résumé 1 High High 157 5.89 1.66 5.50 1.58

Résumé 2 High

Low 157 5.94 1.56 5.59 1.54

4.90 1.53

4.99 1.58

Résumé 3 Low

High 157 4.73 1.81 4.34 1.77 3.80 1.68

Résumé 4 Low

Low 157 5.47 1.62 5.04 1.65 4.48 1.48

Note. On JE is defined as on-the-job embeddedness; Off JE is defined as off-the-job embeddedness: Résumé 1 consisted of high on-the-job and high off-the-job characteristics; résumé 2 consisted of high on-the-job and low of-the-job characteristics; résumé 3 consisted of low on-the-job and high off-the-job characteristics; résumé 4 consisted of low on-the-job and low off-the-job characteristics.

50

The ANOVA analysis consisted of a 2 x 2 x 2 complex mixed design to test the differences of HR professionals’ hireability ratings with respect to hypothesis one, three and four. The three hireability question scores for each résumé were averaged to produce a single hireability score. There were 156 participants who provided ratings for each of the four résumés. Six participants did not provide scores and were removed from the analysis.

High on-the-job versus low on-the-job embeddedness and high off-the-job versus low off-the-job embeddedness were the two within subject variable for this study. The between subjects variable was the grouping of the participants, represented by random assignment to one of two groups during the administration of the survey. The participants in group one rated the résumés first and then completed the other survey tasks, where group two rated the résumé after completing all other tasks. The objective in this between subjects design tested whether the hireability rating scores could be influenced by the order of completing the other measures in the study.