BJR, SWM and Integrity

advertisement

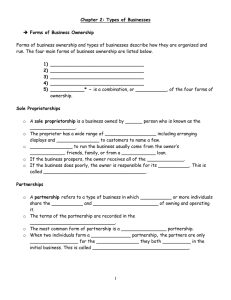

Brian A. Schneider Sustainable Corporations Professor Alan Palmiter Spring 2015 The Lasting Impact of Dodge v. Ford: Balancing the Business Judgement Rule, Shareholder Wealth Maximization, and Corporate Integrity Abstract The core principles of corporate law are the duties of trust and confidence, the fiduciary duties owed by those who manage the corporation to those who nominally “own” the corporation (namely, the shareholders). Among the first things anyone schooled in law or business thinks of when considering the loci that is “corporate law” are Shareholder Wealth Maximization and the Business Judgement Rule. Within the hallowed halls of academia, and amongst the well traversed hallways of corporate America, professors, students, and executives are ensconced in this view of business law and corporate responsibilities. The problem is, the entire system is a myth; a figment created from the ephemera by a trial that was not about what it seemed. The responsibilities and duties of corporate executives and board members as we know them today stem from the decision rendered in Dodge v. Ford. As this paper will explore, however, that decision is as it appears. Perhaps it is time to re-imagine the world of corporate law. New views on corporate integrity, and the sustainable corporation movement, bring forward thoughts and ideas for how we might view the corporation in the 21st century and beyond, and how that might differ from the corporate model established in the early 20th century. Brian A. Schneider Sustainable Corporations Professor Alan Palmiter Spring 2015 The Lasting Impact of Dodge v. Ford: Balancing the Business Judgement Rule, Shareholder Wealth Maximization, and Corporate Integrity Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................................................. 2 2. DODGE V. FORD MOTOR CO. ...................................................................................................................... 2 A. BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................................................. 2 B. BENEATH THE SURFACE ............................................................................................................................................... 4 C. BUSINESS JUDGMENT RULE .......................................................................................................................................... 4 D. SHAREHOLDER WEALTH MAXIMIZATION ................................................................................................................. 5 E. CONFLICTING INTERESTS ............................................................................................................................................. 6 3. CORPORATE INTEGRITY ............................................................................................................................. 7 A. ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT ............................................................................................................................... 7 B. LEADERSHIP AND MOTIVATION .................................................................................................................................. 8 C. TYING IT ALL TOGETHER .............................................................................................................................................. 9 4. LYNN STOUT’S STATEMENT ON COMPANY LAW ............................................................................. 10 A. STOUT’S STATEMENT .................................................................................................................................................. 10 B. STRINE’S REBUTTAL .................................................................................................................................................... 11 C. RECONCILING THE TWO .............................................................................................................................................. 11 5. THOUGHTS FOR THE FUTURE................................................................................................................ 12 1 Brian A. Schneider Sustainable Corporations Professor Alan Palmiter Spring 2015 1. Introduction The core principles of corporate law are the duties of trust and confidence, the fiduciary duties owed by those who manage the corporation to those who nominally “own” the corporation (namely, the shareholders). Among the first things anyone schooled in law or business thinks of when considering the loci that is “corporate law” are Dodge v. Ford Motor Co. (hereinafter, “Dodge v. Ford”), Shareholder Wealth Maximization (“SWM”), and the Business Judgement Rule (“BJR”). Within the hallowed halls of academia, and amongst the well traversed hallways of corporate America, professors, students, and executives are ensconced in this view of business law and corporate responsibilities. Law schools teach it to upcoming lawyers, and business schools teach it to future executives; thus has it been and thus it remains. The problem is, the entire system is a myth; a figment created from the ephemera by a trial that was not about what it seemed, a court that wanted to make a political statement, and a generation of academics who went along with it because it seemed to make sense. Corporate America, business law, and the responsibilities and duties of corporate executives and board members as we know it today stems from the decision rendered in Dodge v. Ford. As this paper will explore and examine, however, that decision is not all that it appears to be on the surface. Additionally, as times have changed and new ideas have been created, perhaps it is time to re-imagine the world of corporate law. New views on corporate integrity, and the sustainable corporation movement, bring forward thoughts and ideas for how we might view the corporation in the 21st century and beyond, and how that might differ from the corporate model established in the early 20th century. As part of that examination, this paper will take a look at Lynn Stout’s Statement on Company Law, in which she promotes and advocates a series of guidelines, and lens through which to view the modern corporation. 2. Dodge v. Ford Motor Co. A. Background Founded in 1903, the Ford Motor Company was and is a model of American business enterprise. Henry Ford was and remains one of this country’s most successful and influential businessmen, alongside more modern counterparts like Jack Welch and Steve Jobs. The Ford Motor Company was so sensationally successful, that in 1911 it paid a regular annual dividend of $1.2 million. Furthermore, between 1913 and 1915, the company paid out special dividends in amounts ranging from $10 million to $11 million. In 1916, however, Henry Ford, the majority shareholder of the company, declared that he would not pay the special dividend, and instead use that cash to fund a new factory at River Rouge which would greatly enhance the company’s production capacity. Ford also planned to increase employee salaries while reducing the price of Ford automobiles. 2 Brian A. Schneider Sustainable Corporations Professor Alan Palmiter Spring 2015 The Dodge brothers, who were amongst the original investors in the Ford Motor Company brought suit against the company, in essence demanding that Ford pay the special dividend and to enjoying Ford from constructing the River Rouge Factory [Dodge v. Ford Motor Co., 170 N.W. 668 (Mich. 1919)]. The trial court found in favor of Dodge on both issues. The Michigan Supreme Court, however, while upholding the lower Court’s finding that Ford was required to pay the dividend, did reverse the injunction against construction of the River Rouge Factory, which remains to this day one of the nation’s largest. In upholding the requirement that Ford pay the special dividend, the Court stated the following about the purpose of a business corporation: A business corporation is organized and carried on primarily for the profit of the stockholders. The powers of the directors are to be employed for that end. The discretion of directors is to be exercised in the choice of means to attain that end, and does not extend to a change in the end itself, to the reduction of profits, or to the nondistribution of profits among stockholders in order to devote them to other purposes. From this statement, a generation of business school academics and future M.B.A’s derived the notion of SWM. The problem, of course, if that the same Court completely contradicts itself both before and after making this statement. It is also worth noting that the abovequoted passage is dicta, and not part of the ruling; and yet it inspired a century’s worth of corporate leadership and guidance. Earlier in the same opinion, the Court quoted that “[i]t is a well-recognized principle of law that the directors of a corporation, and they alone, have the power to declare a dividend of the earnings of the corporation, and to determine its amount.” The Court continues to state that, absent fraud, misappropriation, or “such an abuse of discretion as would constitute a fraud, or breach of that good faith which they are bound to exercise towards the stockholders” courts of equity should not interfere if the corporation refuses to declare a dividend. Later on, the Court continues by stating: We are not, however, persuaded that we should interfere with the proposed expansion of the business of the Ford Motor Company. [… T]he ultimate results of the larger business cannot be certainly estimated. The judges are not business experts. It is recognized that plans must often be made for a long future, for expected competition, for a continuing as well as an immediately profitable venture. The experience of the Ford Motor Company is evidence of capable management of its affairs. [emphasis added] 3 Brian A. Schneider Sustainable Corporations Professor Alan Palmiter Spring 2015 The Court seemed to justify itself, or to address this seeming contradiction, by stating that since “[i]t had been the practice, under similar circumstances, to declare larger dividends...a refusal to declare and pay further dividends appears to be not an exercise of discretion on the part of the directors, but an arbitrary refusal to do what the circumstances required to be done.” (emphasis added) B. Beneath the Surface Underlying the decision in Dodge v. Ford, however, was a vortex of political sub-currents. The Dodge Brothers had intended to use the 1916 special dividend to finance their own new car company, which was meant to compete directly with the Ford Motor Company. Ford’s decision to not pay the special dividend was seen as an attempt to forestall competition, and the benefits that such competition would have had on the Michigan automobile industry. Thus, the real issue at stake in Dodge v. Ford was one of anti-trust violations. Unfortunately, plaintiff’s brought the action in State Court, and could not win on a federal antitrust claim. Instead, they relied on twisted logic to persuade an antagonistic Michigan Court to side against Ford. Under the guise of corporate law, the court used its opportunity to advance a political agenda. Due to Ford’s, perhaps unwise, public persona and statements made to the press and on the public record, the Court was able to paint Ford as an anti-shareholder altruist, and declare his refusal to pay a dividend “arbitrary” and grossly against the interests of the corporation, despite going out of their way to stress the importance of the idea that “judges are not business experts” and that the “experience of the Ford Motor Company is evidence of capable management of its affairs,” presumably by Mr. Ford. Thus, while this case served as the basis of a century’s worth of legal and business education and scholarship on SWM and the concordant duties of corporate managers, it was actually a case that declared that courts had no place second guessing business decisions, and actually hinged on the fears of the Michigan Court of Ford Motor Company’s, and, more specifically, Henry Ford’s rapidly growing power and influence. C. Business Judgment Rule In the aftermath of Dodge v. Ford, and the generations of MBAs and scholarship that followed, it has become standard ideology to accept that public corporations are “owned” by their shareholders, that corporate managers owe fiduciary duties to those shareholders under agency theory, and the shareholder primacy dominates; thus, SWM has become the rule by which corporate managers live. In The Problem of Corporate Purpose,1 Lynn A. Stout questions whether the maxims of SWM and shareholder primacy have lived up to their expected billing. Stout suggests that Lynn A. Stout, The Problem of Corporate Purpose, 48 Issues in Corporate Governance (June 2012). 1 4 Brian A. Schneider Sustainable Corporations Professor Alan Palmiter Spring 2015 the embrace of SWM, especially over the past two decades, should have resulted in vastly improved performance by the business sector. Instead, however, Stout says that business has “have suffered a daisy chain of costly corporate scandals and disasters, from massive frauds at Enron, HealthSouth, and Worldcom in the early 2000s, to the near-collapse of the financial sector in 2008, to the BP Gulf oil spill disaster in 2010.” Contrary to the popular opinion and routine over the past decades to cite Dodge v. Ford as mandating a policy of SWM, the actual corporate law states no such thing. Dodge v. Ford, as discussed above, was a farce of a case; a charade played out on legal grounds. Modernly, the corporate code of Delaware, where the majority of U.S. corporations are incorporated, states simply that “corporations can be formed for any lawful purpose.” This, along with the actual holding from Dodge v. Ford, results in what today is known as the Business Judgment Rule. The business judgment rule essentially states that as personal conflicts of interest, fraud, or willful lack of knowledge, courts will not second-guess managerial decisions about what is best for a corporation—even if those decisions predictably reduce profits or share price. In Air Products, Inc. v. Airgas, Inc. Air Products sought to acquire Airgas at a $30 per share premium. Airgas’ board refuse, and an action was brought to require the sale arguing that Airgas was forced to consider the interests of its shareholders. The Delaware Court failed to find that argument persuasive, and stated that the Airgas Board “was not under any per se duty to maximize shareholder value in the short term.” Here, the Delaware Court uses the BJR to declare that corporations, while operating in the realm of creating profit for shareholders, is not bound to create immediate returns in the near term, but rather, absent fraud or conflict of interest, is free to consider longer term implications. D. Shareholder Wealth Maximization Contrary to Stout’s arguments regarding the BJR, Leo Strine continues to argue the merits of SWM. In Our Continuing Struggle with the Idea that For-Profit Corporations Seek Profit,2 Strine suggests that “any for-profit corporation that sells shares to others has to be accountable to its stockholders for delivering a financial return.” While Strine agrees that Dodge v. Ford stands for the creation of the BJR, he seems to argue that discretion is limited by the “well-motivated, non-conflicted fiduciary.” Thus, Strine argues that the fiduciary, or the executive of board of directors, “be motivated by a desire to increase the value of the corporation for the benefit of the stockholders.” Strine seems to have some justification for his arguments. In a 2010 case pitting eBay against Craigslist, a similar thread to what first appeared in Dodge v. Ford appeared. Here, Craig Newmark and Jim Buckmaster, the controlling stockholders of Craigslist, created a poison pill—a provision which would have diluted eBay’s ownership should their ownership position increase in any way. Newmark and Buckmaster argued that their 2Leo E. Strine, Jr., Our Continuing Struggle with the Idea that For-Profit Corporations Seek Profit, 47 Wake Forest L. Rev. 135 (2012). 5 Brian A. Schneider Sustainable Corporations Professor Alan Palmiter Spring 2015 action was designed to prevent the disruption of Craigslist’s “corporate culture.” Chancellor Chandler, of the Delaware Court, however, ruled that “[d]irectors for a for-profit Delaware corporation cannot deploy a rights plan to defend a business strategy that openly eschews stockholder wealth maximization—at least not consistently with the directors' fiduciary duty under Delaware law.” This holding seems to be at odds with Stout’s definition of the BJR. E. Conflicting Interests Contrarily, however, Stout continues to argue that shareholder primacy, and the principles of SWM, may not, in fact, be all that they seem. This results from the fact that there is no single “shareholder value.” Stout argues that “different shareholders have different needs and interests depending on their investing time frame, degrees of diversification and interests in other assets, and perspectives on corporate ethics and social responsibility.” Stout’s most interesting observation is in the discrepancy between potentially harmful short-term thinking and long term strategic planning that such theories of SWM hold. Stout states quite eloquently: Shareholder value ideology focuses on only a narrow subgroup of shareholders, those most short-sighted, opportunistic, willing to impose external costs, and indifferent to ethics and others’ welfare. As a result shareholder value thinking can lead managers to focus myopically on short-term earnings; to harm employees, customers, and communities; and to lure companies into reckless and socially irresponsible behaviors. This ultimately harms most shareholders themselves—along with employees, customers, and communities. Kent Greenfield also weighs in on the problem of short-term earnings as it relates to management. In The Puzzle of Short-Termism,3 Greenfield talks about one of the problems of the “sustainable corporation” being the nature of corporations to produce externalities. The most usual and obvious externalities produced by corporations are current externalities, such as avoiding environmental regulation, or laying off employees. These current, or short-term, externalities must be balanced against future externalities, which affect the sustainability of the corporation. The problem, as Greenfield puts it, is that “[c]urrent shareholders may prioritize present returns over future returns, and current shareholders may not expect to be future shareholders at all.” This creates an incentive upon managers to please current shareholders at the potential expense of future shareholders, which, in turn, leads to short-termism. In numerous studies conducted, corporate managers admit that they have made decisions expected to be harmful to the corporation in the long-term in order to maximize short-term earnings. And as Greenfield notes, “[i]n 2006, both the Conference Board and the Business Roundtable, two of the 3 Kent Greenfield, The Puzzle of Short-Termism, 46 Wake Forest L. Rev. 627 (2011). 6 Brian A. Schneider Sustainable Corporations Professor Alan Palmiter Spring 2015 nation's most prominent business organizations, issued reports “decrying the short-term focus of the stock market and its dominance over American business behavior.” How then to handle the conflict between the BJR and SWM; between short-term profits and long-term sustainability? 3. Corporate Integrity Thus far we have examined the BJR and SWM; how they relate, how they seem to be at odds with one another, and how some have tried to reconcile the two. We’ve also discussed how both came to be more as a result of common perception and scholarship than actual legal machination. It seems like it might be hopeless to try to reconcile these two ideologies independently. However, a third ideology exist, currently separate from the BJR and SWM, but one that may be able to bridge the gap between the two. Corporate Integrity is a way of looking at the corporate body that is different from either the BJR or SWM. It’s more psychologically and behaviourally based than business or legally; but these fields are not mutually exclusive, and, in fact, should be fused together. In the following sections, this paper will discuss various mechanisms and theories used in organizational behaviour research that may impact corporate integrity, and help bridge the gap between long-term and short-term thinking; between the BJR and SWM. A. Organizational Commitment Organizational commitment is the study of the degree to which members of an organization (e.g., employees) assume the goals and objectives of the organization as their own. Organizational commitment is also closely tied to the ideas of organizational identification and organizational culture. The differences are mostly degrees of nuance. Commitment deals with the degree to which employees adopt organizational objectives as their own; identification deals with the degree to which employees identify with organizational missions and value; and culture is the broader study which may encompass both commitment and identification, but also includes measures of employee satisfaction, and how employees interact with each other and management in order to promote an effective and efficient organization. The level of commitment within an organization has been shown to be tied to factors such as turnover rate, job performance, and organizational citizenship behavior. Factors which influence the level of organizational commitment include role stress, the degree of employee empowerment, and the level of perceived job security. Organizational citizenship behavior is a particularly interesting concept. It describes the degree to which employees become committed to such an extent that they act of their own volition, and above and beyond the duties proscribed by their job description, to advance organizational objectives. The idea that, within high functioning organizations, employees 7 Brian A. Schneider Sustainable Corporations Professor Alan Palmiter Spring 2015 actually become so independently invested in the organizational mission as to actively and independently seek out means by which to advance organizational objectives seems to offer evidence contradicting the cry for the necessity of strict regulation and performance incentives to maximize output. B. Leadership and Motivation Within the educational setting, studies in leadership and motivation are geared mainly towards managers, in seeking to understand how to better inspire employees to achieve the sought after level of organizational commitment, thus producing these organizational citizenship behaviors. While there are any number of suggested methods of motivating employees towards organizational commitment, many are centered or founded on the equality or justice theories of behavior. This theory suggests that, within an organizational or employment context, employees desire to belong to an equitably distributed equilibrium, and seek employment and organizations where they believe that their contributions and interactions are treated fairly and justly. This sense of equity or justice can be described as having three separate facets: distributive, procedural, and interactional. Distributive theories of justice and equality focus on employees feeling that they are receiving fair compensation for their inputs (i.e., job performance). But it’s not sufficient to say that an employee feels properly compensated, but more so it’s a function of whether the employee feels that his or her compensation is equitable in relation to the compensation of their peers. That is, given similar inputs, compensation across an organization should be about equal. Employees accept that greater performance inputs (generally associated with positions of greater responsibility) ear greater compensation, but there exist a general sense that, given equal performance inputs, compensation should reflect that equality. Procedural justice focuses on the degree to which employees feel that they have an appropriate avenue for voicing concerns and achieving feedback. This is an area where business education again focuses on management philosophies, as managers are taught key words like “open door policies” that help to foster procedures by which employees can get feedback. Employees also like to feel secure in their employment, so another aspect of procedural justice is the sense that negative action won’t be taken against the employee without first giving the employee notice of any deficiency, and the opportunity to remedy or improve. Interactional justice focuses on the way in which members of the organization behave with one another. Key aspects of interactional justice include the level of respect that is show to the employee by both peers and management, as well as the degree and manner of communication between organizational members. 8 Brian A. Schneider Sustainable Corporations Professor Alan Palmiter Spring 2015 C. Tying it all Together This is where corporate integrity begins to play a role. In Integrity: A Positive Model that Incorporates the Normative Phenomena of Morality, Ethics, and Legality, Erhard, Jensen, and Zaffron redefine “integrity” for the corporate world, and how it can be used to increase performance amongst individuals and groups. Erhard, Jensen, and Zaffron argue that “[t]he philosophical discourse, and common usage as reflected in dictionary definitions, leave an overlap and confusion among the four phenomena of integrity, morality, ethics, and legality.” Integrity is defined not so much in normative terms (i.e., what is “good” or “bad”) but rather as the completeness of system for workability. The authors use the example of the bicycle wheel, where once you start removing the spokes, the wheel loses its integrity, or ability to perform. Thus, a corporation’s integrity is that sense of completeness that enables it to achieve maximum performance. In the above Section B: Leadership and Motivation, I spend time writing about theories of justice and equality as it relates to motivating employees to perform to their full potential. Whether distributive, procedural, or interactive, all these theories have in common themes of security, equity, and wholeness; which begins to sound a lot like Erhard, Jensen, and Zaffron’s definition of integrity. In future research, perhaps these areas may be fused, and scholars may recognize that by developing motivational styles based on theories of overall corporate integrity, and promoting a legal atmosphere that embraces and enhances a corporations ability to act in a manner consistent with its “wholeness,” or corporate mission, instead of SWM. In Corporate Governance Going Astray: Executive Remuneration Built to Fail, Jaap Winter argues against the agency relationship of corporations and the resulting drive in the 1990s to align managerial interests (the agents) with those of their principals (the shareholders) by creating performance based pay and incentives. In the U.S., this primarily took the form of stock options and bonuses based on meeting specific performance goals. As mentioned above, however, this increased pressure on managers to meet the needs of short-term investors at the expense of sustainable long-term objectives. Jaap argues that “performance based pay for executives not only suffers from the original criticism of bad governance and poor design, but that it cannot be made to work because people behave differently than performance based pay assumes.” As I understand it, the problems that Winter espouses about executive pay are based on the notion that the mechanisms created inherently undermine the corporation’s integrity. Winter suggests that some of the important myths of executive performance pay are that “performance based pay for executives actually enhances overall performance of companies; when executives lead companies to higher performance they are entitled to receive part of the gains; executives only perform well when they have “skin in the game;” substantial performance based pay is essential to retain first class managers in an international market for executive talent; and financial rewards are the key indicators of personal success.” 9 Brian A. Schneider Sustainable Corporations Professor Alan Palmiter Spring 2015 Winter, however, provides the example of a survey of Dutch banking executives by David de Cramer, an professor of Behavioral Business Ethics, who could that each of the banking executives “believed that others in the banking world find bonuses more important for performing well than they themselves do.” Additionally, when asked to make a choice between two bankers to manage their personal wealth, every executive surveyed chose the banker with a genuine interest in banking matters and who wants to provide service to customers over the banker interested in his own financial incentives. Winter suggests that Boards: (1) Make remuneration less significant; (2) benchmark internally instead of externally; (3) reduce variable pay substantially and use a wide set of collective targets; (4) explore employee’s real motivations; and (5) provide for corporate integrity. In discussing motivation, Winter points out that three factors stand out: “autonomy, mastery and purpose” (which sound similar to those espoused above under distributive, procedural, and interactional justice as it pertains to organizational motivation). It all ties back to the concept of integrity, and that a corporation’s efforts will be maximized by the corporation being “whole and complete,” which likely has more to do with adhering to a corporate mission or purpose than maximizing shareholder’s short-term wealth. 4. Lynn Stout’s Statement on Company Law A. Stout’s Statement Lynn Stout has released a Statement on Company Law that attempts to clear up certain misconceptions about corporate law that are widely held but not necessarily true; among these misconceptions are the discrepancy between the ideas of the BJR and SWM. Stout espouses ten different statements about the nature of corporate law, many of which seem commonly understood and non-controversial. For example, in Statement 1, Stout writes that “[c]orporations are universally treated by the legal system as “legal persons”…[which] ensures that corporations have certain rights.” Stout includes among those rights the “right to own property, enter contracts, and commit torts in their own names.” Similarly, in Statement 4, Stout writes that a feature of “corporate personhood” is that corporations “own their own assets and incur their own liabilities…separate from shareholder assets and liabilities.” It is from this statement that we arrive at the concept of “limited-liability” for corporate shareholders, although Stout suggests that this would be better labelled as “no-liability.” However, Stout also espouses some views on corporate law that are more controversial. In Statements 2 and 3, Stout talks about the ownership of corporations by shareholders, and what exactly a stock-share is. In Statement 2, Stout writes that contrary to common perception, “shareholders do not own corporations; nor do they own the assets of corporations.” Instead, Stout argues, shareholders shares of stock, which are no more than “bundles of intangible rights, most particularly the rights to receive dividends and to vote on limited issues.” Continuing in Statement 3, Stout writes that “only shareholders who 10 Brian A. Schneider Sustainable Corporations Professor Alan Palmiter Spring 2015 purchase shares in the primary market directly contribute assets or cash to the corporation…[s]hareholders who purchase shares in the secondary market do not contribute capital (or anything else) to corporations.” Stout concludes by recognizing that “the notion that shareholders contribute capital to corporations is thus wrong in the great majority of cases.” Also, in Statement 8, Stout argues against the agency-theory of corporations, stating that “[c]orporate oiffcers and employees are agents for the corporation as a separate, propertyowning legal entity….not the agents of the shareholders or any subset of shareholders.” Additionally, Stout argues that the law generally recognizes that “the medium to long term interests of this separate entity may not be synonymous with the short-term financial interests of its shareholders.” This is directly contrary to the widely held notions of agency-theory in corporations, though this theory has recently begun to see increasing backlash, even amongst its original proponents. Stout’s biggest departure from common understandings, however, and most contentious argument, is in Statement 10, where she argues that “corporate directors generally are not under a legal obligation to maximize profits for their shareholders…[as] reflected in the acceptance in nearly all jurisdictions of some version of the business judgment rule.” Stout continues to state that directors do sometimes, if not often, seek to maximize short-term profit or shareholder value, but not as a product of legal mandate, but rather as the result of “pressures imposed on them by financial markets, activist shareholders, the threat of a hostile takeover and/or stock-based compensation schemes.” B. Strine’s Rebuttal Stout’s arguments are not universally accepted, however. Leo Strine, the Chief Justice of the Delaware Supreme Court, in fact, has responded vehemently against Ms. Stout. In his article, The Dangers of Denial: The Need for a Clear-Eyed Understanding of the Power and Accountability Structure Established by the Delaware General Corporation Law, Strine takes particular exception to Stout’s Statement 10. Strine suggests that Stout and her supporters “do not argue simply that directors may choose to forsake a higher short-term profit if they believe that course of action will best advance the interests of stockholders in the long run, they argue that directors have no legal obligation to make…the promotion of stockholder welfare their end.” Strine sharply criticizes those who “pretend that directors do not have to make stockholder welfare the sole end of corporate governance within the limits of their legal discretion.” C. Reconciling the Two Unfortunately, I think this is a case where two sides have taken an adversarial approach to working together, and have, at times, perhaps taken their sides to the extreme ends of the ideological spectrum instead of recognizing commonalities and meeting in the middle. 11 Brian A. Schneider Sustainable Corporations Professor Alan Palmiter Spring 2015 When Strine criticizes those who “pretend that directors do not have to make stockholder welfare the sole end of corporate governance within the limits of their legal discretion,” he is referring to long-term shareholder welfare, not necessarily short-term SWM. I, however, don’t interpret Stout’s statements, nor Statement 10 in particular, to suggest that. Instead, I interpret Stout’s statement that “corporate directors generally are not under a legal obligation to maximize profits for their shareholders……[as] reflected [by]…the business judgment rule” to mean short-term SWM. As evidence for this interpretation, I refer back to Statement 10, where Stout argues that the law generally recognizes that “the medium to long term interests of [the corporation] may not be synonymous with the short-term financial interests of its shareholders.” Regrettably, in his article, Stine is able to reference signatories of Stout’s Statements as examples of those who take the Stout’s Statements as I interpret them too far, so as to suggest that shareholder concerns and welfare may be completely subrogated by the corporate directors at their discretion. I think the main underlying problem that exists is the one between a corporation’s ability to use its business discretion to make decisions that it believes are in the long-term best interests of the corporation—and by extension, its shareholders—and the pressure to make decisions that are in the short-term interest of SWM or executive compensation, even at the expense of sustainability. I think that’s what Stout is trying to convey with her Statement on Company Law. Unfortunately, I think her language is ambiguous enough, and that enough controversy has been created between it, some of its signatories, and other parties (such as Strine), that as it stands, it is a futile gesture. As such, I would not necessarily recommend signing the Statement as it exists, but rather encouraging all interested parties to try to find the common ground, where shareholder interests intersect with corporate interest, and the corporate interests may include sustainability and other goals beyond mere monetary SWM. 5. Thoughts for the Future Dodge v. Ford Motor Co., Shareholder Wealth Maximization, and the Business Judgement Rule still stand at the center and heart of corporate law education and practice in the United States. However, the controversial division amongst scholars over the fundamental discordance between the BJR and SWM is not as hopeless as it may initially appear. Over the years, arguments have been made supporting both, but neither is based so firmly on solid legal ground as to provide conclusive evidence one way or the other. SWM, while dicta in Dodge v. Ford, has grown in the common sphere to be ubiquitous, while the BJR can equally not be denied as having a place in our nation’s courts. However, it seems that the main argument at the present time is that between whether corporation’s must embrace the principles of SWM to the exclusion of all other goals, and 12 Brian A. Schneider Sustainable Corporations Professor Alan Palmiter Spring 2015 whether SWM means short-term or long-term, or whether, in a corporations sound business judgment, it may exercise its discretion to focus on corporate goals and missions that may not coincide with the short-term interests of its shareholders, but rather the longterm sustainability and interests of the corporation, and by extension, it’s shareholders. This is where I feel there is a middle ground to be found. When viewed in light of arguments and theories on organizational motivation, integrity, and executive compensation, it seems clear that there is a case to be made that corporations function at their best when the primary guiding goals are those of corporate mission and integrity, as opposed to strict financial gain. If these theories can be expanded on and accepted, it becomes easier to see how corporate focus on shareholder welfare may mean more than short-term shareholder wealth maximization, and be more about the long-term sustainability of the corporation itself, and its mission. 13