Working Memory - Somerset Learning Platform

Working Memory

A guide for SENCOs and teachers

1

March 2015

Contents

What is ‘working memory’ and how does it differ from other forms of memory?

How does working memory operate?

What might I see in the classroom?

What is the impact of poor working memory on learning?

How can I identify difficulties and assess working memory?

How can I help?

Further reading

2

What is working memory and how does it differ from other forms of memory?

Working memory deficit is a difficulty which is often overlooked and not fully understood by teachers. The impact in the classroom can be huge - across the whole curriculum - and the understanding of what working memory is, what constitutes a high working memory load and how this can be reduced and supported is essential in developing successful classrooms for all pupils.

Definition

‘ Working memory is the term used to refer to the ability we have to hold and manipulate information in the mind over short periods of time. It provides a mental workspace or jotting pad that is used to store important information in the course of our everyday lives’

(Sue Gathercole 2008).

It is thought that working memory is central to an understanding of how people think and is closely associated with learning. It encompasses the skills that underpin reasoning, remembering and more recently has been linked to a person’s ‘consciousness’. Pupil’s abilities in the in key areas of reading, writing and mathematics can be closely linked to their scores on working memory tests.

Weak working memory is also known to be a component of the specific learning difficulty of dyslexia as it affects the pupil’s ability to retain and recall phonological information.

In order to understand working memory and how it operates in our daily lives it is important to understand the different forms of memory that store a variety of information – some of which are permanent stores and others more fleeting.

3

Procedural Memory is formed of learned skills involving co-ordination of physical movements such as writing your name or driving a car. Once established these memories last a lifetime.

Semantic Memory is where we store items of information that we frequently use or are exposed to; the capital of France, 5+5, the name of the first woman prime minister. If this information is frequently used – retrieved from the memory store

– it will last a lifetime. However it will become more difficult to access if it is not used.

Autobiographical Memory is the store of facts and significant events from your life such as a wedding day, first day at school. It comprises lots of sensory memories of feelings, sound, smell, taste and sight.

These stimuli make the memories very strong and they can be easily brought back by experiencing the same sounds (eg. songs), smells and other sensory stimuli.

Episodic Memory records the details of particular experiences and only lasts for up to several days – the time that you need to store that particular information. For example remembering that your supermarket delivery is due at 10am tomorrow.

Once the need for that particular memory has passed then it will fade.

4

It is estimated that 1 in 10 pupils have a significant difficulty with Working

Memory that impairs their learning; this equates to 3 pupils in an average classroom

Some examples of tasks that depend on working memory / place a high demand on working

Following directions such as ‘When you have put your maths books on my desk find your reading books and sit on the carpet’

Hearing an unfamiliar word – such as in a foreign language - and attempting to repeat it several seconds later

Adding up and remembering the total amount spent as you select items from shelves at the supermarket and add them to your basket

Remembering to measure and combine the correct amounts of ingredients (rub in 50g of margarine and 100g of flour, then add

75g of sugar) when the recipe is no longer in view

5

It is often said that the average adult cannot hold more than six or seven units of information in working memory. A unit of memory depends on whether or not the material to be remembered is organised in a meaningful way or not.

Combining two sources of memory – working memory and memory for meaning – boosts memory performance dramatically

Once information has been lost from working memory it cannot be recovered; the only option is to start again. Trying to ‘think back’ will not retrieve the information as the memory traces are no longer there. This could explain why a child may stare blankly at a teacher when asked what he or she should be doing next. It is important that such memory failures are recognised in the classroom and that the teacher and pupils work together to

6

How does working memory work?

There are four main parts to the currently recognised working memory model. These are Verbal Short –term Memory ( Phonological Loop) ,

Visuo-spatial Short-term Memory (Visuo-spatial sketchpad), what is commonly known as the Central Executive , and finally the Episodic

Buffer.

Instead of all the received sensory information going into one single store, these are the different systems for dealing with the different types of information.

The Visuo-Spatial Sketch Pad (VSS) or inner eye stores and processes information in a visual or spatial form. The VSS is used for navigation.

7

The Phonological Loop (PL) is the part of working memory that deals with spoken and written material. It can be used to remember a phone number. It consists of two parts

Phonological Store (inner ear) – Linked to speech perception

Holds information in speech-based form (i.e. spoken words) for 1-2 seconds.

Articulatory control process (inner voice) – Linked to speech production. Used to rehearse and store verbal information from the phonological store.

The labels given to the components of the working memory reflect their function and the type of information they process and manipulate. The phonological loop is assumed to be responsible for the manipulation of speech based information, whereas the visuo-spatial sketchpad is assumed to be responsible for manipulating visual images. The model proposes that every component of working memory has a limited capacity and also that the components are relatively independent of each other.

Central Executive : Drives the whole system (e.g. the boss of working memory) and allocates data to the subsystems (VSS & PL) which controls attention and higher –level mental processes involving coordinating storage and mental processing. It also deals with cognitive tasks such as mental arithmetic and problem solving.

The Episodic Buffer is the most recent addition to the working memory model and is thought to be a ‘multi-modal store’. This means that is does not just store information in one form such as visual or auditory. This means it is unlike the VSS or PL the episodic buffer is thought to bind together information and therefore give us a sense of consciousness – integrating information into a coherent episode.

Noteworthy facts from the described model of working memory are:

Each of the four components has its own limited capacity

There are links running in both directions between each of the individual stores and the central executive

8

There is no corresponding path between visuo-spatial and verbal short-term memories

It is worth noting that the term ‘Short term memory’ (STM) is commonly used to describe situations in which the individual simply has to store some material without manipulating it or doing something else at the same time. E.g. remembering a telephone number. Working memory tasks tend to tax the central executive, and are more complex than short term memory tasks, involving storage and manipulation.

POINTS TO REMEMBER

Working memory is used to hold information in mind and manipulate it for brief periods of time. Pupils often have to hold information in order to be engaged in effortful activity.

Working memory is limited in capacity which varies between individuals and is affected by the characteristics of the task.

Working memory is a series of linked components.

Short term memory involves storage, whereas working memory is involved with storing and processing.

Information is lost from working memory when we are distracted (including noise and movement) or its limited capacity is overloaded.

9

What might I observe in the classroom?

In this section, the characteristics of a child with working memory difficulties will be described. The types of activities that place a high demand on working memory will be explained and some examples given.

What might I see if working memory is a problem?

Why might I be seeing it?

The boys, as a group, are making less academic progress than the girls.

Booster and catch up groups have more boys than girls.

It’s usually boys names that the teacher calls to

‘hurry up’

More boys than girls have working memory problems.

In a pre-tutoring group, they appear to have understood the topic and are confident to talk.

However, when the topic is covered in class, they are silent unless called upon, in which case they look very nervous.

They can’t answer questions in a large group that they have previously answered in a smaller group.

They have one or two close friends and dislike large group games.

They are often in trouble with pe ers for ‘getting the game wrong

Larger groups place more demands on working memory.

10

They ‘have to’ shout out the answer before they forget it. If made to wait before they are asked, they may open their mouths to answer and then forget what to say.

Having to store information and process new information at the same time is difficult.

They may start a task off well but when the teacher stops the class to do a ‘pit-stop plenary’, they cannot remember where to start again afterwards.

They are easily distracted by people around them chatting or doing other activities.

Their mental maths is significantly below their ability if given a pencil and paper and more time.

They can read the words but not be able to tell you what they’ve read. But when it is read to them, their comprehension improves.

A lesson or activity may start off well but not be finished to the same standard.

Working memory is easily overloaded

Long discussions may end with disruptive behaviour.

After a good start you may notice them ‘zoning out’

Work is rushed and finished early.

They are the last to carry out instructions

They may be watching others a lot

They ask their friends to clarify tasks

Holding and manipulating instructions is difficult

If interrupted in the middle of a task, they struggle to re-start.

They may miss whole steps out when attempting a task.

11

Common high working memory loads activities often seen in schools:

Remembering sequences

Counting patterns (times tables) especially when reversed e.g. turning a multiplication sum into a division fact mentally.

Multi-step sequences to answer questions e.g. long multiplication.

Copying unknown words off a board e.g. new vocabulary.

Writing lengthy sentences containing content that has not been fully understood.

Following lengthy instructions

A homework instruction given verbally at the end of the lesson after the bell has gone.

Instructions that use the word ‘if’ and ‘or’ e.g. ‘if you have done p45 you can chose to do worksheet 1 or worksheet 2. Otherwise you have to do p45 or p46.’

Instructions given out of order e.g. ‘before you do the green worksheet you must have put your book in the red box but only do this after you have the date and title’.

Keeping track of the place reached in the course of multi-level tasks

A 3-step question in maths.

Any problem solving activity.

Coursework.

12

Copying from the board.

Navigating around a school.

Collecting equipment needed for a task.

Writing the date, title and learning objective before attempting the task.

13

What happens when working memory is overloaded?

The learning difficulties that pupils with poor working memory face arise because they are unable to meet the memory demands of a learning situation. This leads to memory overload and information – such as the sentence they were going to write – is lost. This loss can be described as ‘catastrophic’ as it cannot be recovered. This means that the child cannot continue with the activity and complete it successfully unless he or she is able to access again the critical task information that is needed.

If this information is not available then either the child will need to guess

(which can lead to errors) or give up.

Many structured activities place excessive demands on working memory for many individuals, as they require the pupil to hold substantial amounts of information, often while completing another mental activity.

They are often described as failing to check work for mistakes and careless errors, producing work that is ‘sloppy’ and poorly organised. In order to check whether work is correct needs a comparison with the original instruction, which is probably out of the question for a pupil with poor working memory

This failure of working memory slows the rate at which pupils can accumulate key knowledge and skills, especially vocabulary.

14

POINTS TO REMEMBER

• Pupils’ progress in reading maths and science is closely related to their working memory capacities, across the full range of school years.

• Poor working memory performance does not appear to be due to more general factors such as language difficulties or non-verbal ability.

• The poor rates of learning in pupils with low working memory capacities are due, in large part, to memory overload.

• The pupil may appear to be inattentive and highly distractible, probably due to memory overload and forgetting.

In summary, any task that requires a pupil to hold information in their heads and then use it to complete a task will place a demand on working memory. This is especially true when asking a pupil to remember or follow instructions or sequences. This will be mostly seen in reading, writing, maths and transferring from one activity to another.

When demands are too high, the pupil may appear to be distractible and lack concentration. Their behaviour may deteriorate or they may become heavily reliant on their peers for support. There may be discrepancies in their work depending on the setting, the time of day and the type of support given.

15

What is the impact of a poor working memory in the classroom?

Working memory capacity is one of the most important cognitive indicators linked to academic attainment in key areas of the curriculum such as reading and maths.

It is the ability to hold and use information for a short period of time e.g. manipulating numbers in mental maths tasks.

It depends upon capacity understanding focus processing

This is linked to age and increases until mid-teens and begins to fall in mid-thirties

Having the ability to understand the language used in order to respond to questions and formulate answers

The ability to focus on the task and not be distracted

In order to complete a task, information has to be processed

Although working memory in childhood increases with age it can differ substantially from pupil to pupil. Accordi ng to most researchers a pupil’s relative capacity is established by the age of four and is unlikely to change without intervention.

Learning activities in the classroom help the pupil to gradually accumulate the knowledge and skills they need to become competent in areas such as reading and maths over the years.

16

Poor working memory provides a relatively general constraint on progress. Pupils with low working memory capacities become overloaded by structured learning activities causing them to forget crucial information.

Poor working memory performance does not appear to be linked to more general factors such as low IQ or language difficulties.

If a pupil is already behind its peers in their primary years they are likely to fall further behind in their secondary years. Poor working memory affects all areas of learning from getting from A to B around school to the ability to copy notes from the board or do simple calculations.

Activities that place minimal demands on working memory should not be affected by high anxiety levels but if anxiety and working memory loads are high, performance will suffer

17

How can I identify difficulties and assess working memory?

There are a number of ways to assess whether or not a student has an issue with working memory:

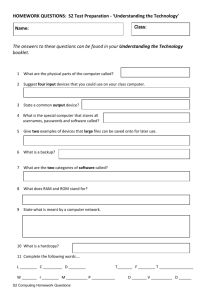

Checklists

Digit memory assessment

Non word repetition assessment

Specific assessments that exist purely to test for working memory difficulties.

However, before assessment is started, it is important to make sure that the child is considered holistically. Many factors can impact negatively upon memory e.g. tiredness and stress and it is important that these are addressed before any assessment process is started.

Checklists

Initially, an informal checklist, such as the Cogmed one below, may be used to identify whether the student has a specific set of behaviours that would appear to be consistent with working memory difficulties. These checklists can be tailored to be subject or age specific. At this stage, demands on working memory should be reduced and the effectiveness monitored.

More formal checklists exist, such as The Working Memory Rating Scale available through Pearson . This is an assessment completed by a member of staff who knows the pupil and makes judgements against a series of statements relating to working memory based on observations.

The total score is then linked to a scale indicating the likelihood of difficulties and the extent to which a difficulty could be severe in nature.

It is useful as an initial investigation and it adds to evidence gained from other sources.

18

Working Memory Checklist (Cogmed)

An individual may be constrained by working memory capacity if he/she:

1. Is easily distracted when working on or doing something that is not highly interesting.

2. Has trouble waiting his/her turn, for example in a conversation or when waiting in line to get help.

3. Struggles with reading comprehension and has to read through texts repeatedly to understand.

4. Struggles with problem solving that requires holding information in short term memory. The child is then required to repeat a given string of average levels. The Backward Digit Span (from the Dyslexia

8. Struggles to understand the context in a story or a conversation.

Screening Test – Secondary) performs the same test of working to be done in separate steps.

Phonological Working Memory Test (from the PhAB2)

10. Has difficulty staying focused during cognitive-demanding tasks, but

Again, for primary aged pupils, this test requires the child to repeat (not attends well when cognitive demands are minimal. read) a list of non-words of increasing length and complexity. It is also

12. When called on, forgets what he/she was planning to say.

If the results of simpler tests and checklists, and the accommodations that they inform, do not produce results, it may be necessary for more in depth analysis to be undertaken.

19

AWMA (Automated Working Memory Assessment)

This is a completely computerised assessment that can be done at three levels – a screener, a short form and a long form. It is suitable for pupils and young people aged 4 to 22 years.

TOMAL (Test of Memory and Learning)

This is a broader assessment of memory and its impact on learning

20

What can I do to help?

It is very important to recognise working memory failures so that the structure of learning activities can be modified. Identifying such failures can be seen through such errors as

Incomplete recall of a sentence or sequence of words

Failure to follow instructions

Place keeping errors

Task abandonment

Remember that children are often acutely aware of their memory difficulties – even from a young age.

Working memory demands can be reduced through using the following strategies:

Consider your teaching style and lesson planning

Review previous lesson information

Provide a visual model/example so that the pupil knows what is required

If a pupil forgets some or all of what they have to do be prepared to modify how the learning activity is presented

Ask your pupil to regularly repeat crucial information – this strategy of rehearsal is crucial to support verbal short-term memory

An adult or other pupil can act as a memory guide or listening buddy

Chunk words and information into steps that they can do one at a time

Use language that is simple in both vocabulary and phrasing

Shorten sentences

Be prepared to repeat key facts

21

Use memory prompts such as pictures, numbers or symbols to represent the sequence of activities

Where possible include movement and rhythm as a moving image is more likely to be remembered

Encourage the pupil to draw or map out their thoughts using diagrams or flow charts

Help them to make connections/links to what they already know

Use aids such as digital recording devices and tablets to help your pupil retain the essential information

Teach the pupil to use useful tools such as a ruler/number line, table square, calculator, hundred square accurately

Play ‘pairs’ matching games or SNAP e.g. - a few scientific words to match to their simplified definition played on a regular basis will help them to recall that fact

Make up a simple story that uses items/objects that need to be remembered that can be visualised

Encourage all children to ask focussed questions when they realise they have forgotten what to do

Teach them to juggle!

Juggling uses both sides of the brain and can improve memory and concentration.

22

Is there anything we can do to help older students?

Older pupils tend to struggle with lecture-based presentations which require them to attend, listen, understand new material and take notes.

They often find it hard to maintain concentration over longer lessons and to organise large amounts of material from different sources in a coherent manner.

It is important to recognise working memory failures and ensure that all staff working with a student who has a poor working memory are aware of that fact

Aim to reduce working memory loads by reducing the amount of information to be remembered

Use the same routines each day to reinforce learning

Use visual aids or encourage pupil to draw pictures to help them to recall an activity linking it to an emotion if possible

Repeat important information or provide a peer buddy for additional support

Encourage the use of memory aids such as personalised dictionaries, table mats, topic posters, memory cards, key rings, number lines, Dictaphones and ICT

Help the student to identify what helps them best to recall, retain and process information.

- repeating information to themselves silently or out loud

- breaking down numbers or letters into chunks

- linking to known information

23

Develop the student ’s own strategies such as asking for help, rehearsal, place keeping and note taking

Encourage them to review notes before going to sleep

The diary/homework organiser is an essential piece of equipment at secondary level and students must take responsibility for it themselves. Note the date given but also record when due in to help reduce overload at the end of the lesson

Students need to write exactly what is discussed / taught as it may be a while before the homework task is looked at again and brief notes may not be enough

Adults or a peer buddy need to check that the task has been understood and recorded correctly

Encourage use of a highlighter to pick out key words or facts. The first sentence in a paragraph is usually a ‘power sentence’ as it often contains a key fact

Consider how technology such as iPads can be used to photograph mind maps, homework tasks and group notes

Older students are more effective at using their own strategies to overcome working memory related problems.

24

Glossary

Autobiographical memory - The long term memory system supporting memory for significant events across a lifetime

AWMA - The Automated Working Memory Assessment, a computerised test battery that assesses an individual’s capacity in each subcomponent of working memory

Central Executive - The sub-component of working memory that controls attention and co-ordinates activity both within the working memory system and between working memory and other cognitive systems such as long-term memory

Chunking - The grouping together of individual items into an integrated whole to enhance recall, typically using long-term memory

Episodic Memory - The long-term memory system supporting memory for events in the relatively recent past, typically spanning minutes through to days

Long-term Memory - Memory for experiences that occurred at a point in time prior to the immediate past, and also for knowledge that has been acquired over long periods of time. Long-term memory systems include episodic memory, autobiographical memory, semantic memory and procedural memory

Memory cards - Individualised memory prompts used in the classroom

25

Memory Guide - A child nominated to assist a fellow pupil with memoryrelated difficulties

Memory Span - A measure of the maximum amount of material that an individual can successfully remember on a test of working memory

Procedural memory - Long term memory for skills such as cycling that have been acquired through repeated practice and that can be executed

‘automatically’, without mental effort

Rehearsal - The voluntary act of mentally repeating information, typically with the aim of prolonging its storage in working memory.

Rehearsal is a particularly important strategy associated with verbal short-term memory

Semantic memory - The long-term memory system supporting knowledge such as facts and word meanings

STM - Short-term Memory. The ability to hold information in mind for short periods of time

Verbal Short-term Memory - The sub-component of working memory that stores verbal information

Visuo-spatial - Relating to abilities or information that can be expressed in terms of physical characteristics relating to vision, space or movement

Visuo-spatial short-term memory - The sub-component of working memory that stores information relating to vision, space or movement

26

Working Memory - The ability to hold and manipulate information in mind for brief periods of time in the course of on-going mental activities, consisting of a system of four sub-components, verbal short-term memory, Visuo-spatial short-term memory, central executive and episodic buffer

Working memory capacity - The limit on the amount of information that can be held in working memory. Each sub-component of working memory has its own limit

27

Where else can I look for information?

Working Memory and Learning – A practical guide for teachers

By Susan E Gathercole and Tracy Packam Alloway Sage

Ready Set Remember

By Beatrice Mense, Sue Debney and Tanya Druce

The Learning Brain: Memory and Brain Development in Children by Torkel Klingberg and Neil Betteridge

Mind Maps For Kids: An Introduction by Tony Buzan

Differentiation Through Learning Styles and Memory by Marilee B. Sprenger

Understanding Working Memory by Tracy Packiam Alloway

28