McNAIR Research Proposal Andy Nez

advertisement

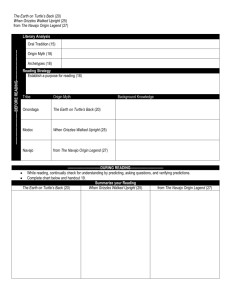

Diné Youth as Third-Gender Identifiers at the Dawn of the 21st Century Diné Youth as Third-Gender Identifiers at the Dawn of the 21st Century Andy Nez McNair Research Proposal University of New Mexico Diné Youth as Third-Gender Identifiers at the Dawn of the 21st Century 1 Table of Contents Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………2 Introduction/ Background…………………………………………………...……………….3-4 Research Inquiry and Question ……………………………………………………………...4-5 Purpose ………………………………………………………………………………………5-6 Review of Literature …………………………………………………………………….…...6-9 Methodology …………………………………………………………………………………9-11 Research Site…………………………………………………………………………………11 Theoretical Framework……………………………………………………………………….12-13 Limitations …………………………………………………………………………………...13 Results ...……………………………………………………………………….…………….13-14 Significance/ Implications …………………………………………………………………...14-15 Timeline/ Plan of Work ……………………………………………………………………...15-16 Bibliography …………………………………………………………………………………17-18 Appendixes …………………………………………………………………………………..19-21 Diné Youth as Third-Gender Identifiers at the Dawn of the 21st Century 2 Abstract This study will examine the traditional historic views and experiences of Navajo thirdgender identifiers (TGI’s) that support today’s TGI’s, who learn and express Navajo tradition far more than those who identify as non-TGI1. I will conduct 10 interviews with Navajo third-gender identifiers from the University of New Mexico to gain a deeper understanding about what are some of the influences and life’s contributions that support how TGI’s express and excel in Navajo philosophy. The views that define TGIs were spiritual and respected, but unfortunately, today those views are more negative as the notion of colonization, primarily genocide, made a deep impact on the lives of the Navajo people. This research can be seen as a contributing factor to the field of history, with further implications in ethnography, Native American studies and Navajo studies. In the era preceding colonization of the Navajo Nation, TGI’s were revered for their spirituality and family wealth. Throughout our history we have tolerated barbarous acts and policies such as the Long Walk of 1864, the Boarding School Era (Early 1900s – 1920s), and the Navajo Nation Diné Marriage Act of 2005. These historical events as well as other effects of Westernization have diminished the reverence toward TGI’s within the Navajo community and the cultural context within Navajo philosophy. Although TGI’s experience exclusion from both Navajo and Western society, the pride for Navajo philosophy and practice remains active within the Navajo TGI community. Since the establishment of Native American studies in the academy in the 1960s, limited literature exists about this subject. Given the complex multi-national sovereignty of the Navajo Nation, the effects to TGIs are felt doubly in the community. The following phenomenological qualitative study constructed under a Navajo based methodology will be inclusive on the thematic roles, influences, and experiences from the interviews with support from historical sources written about Navajo TGI. The first stage will introduce the historic relativity of my topic. I will look at the history of TGI’s and find what enabled TGI’s to make their proficiency levels to remain greater while the second stage includes a thematic paper regarding the influences detected within the interviews. Stage three of this study will generate implications about how my study will promote positivity in the Nation as a whole while showing and exposing my participants as the essential center of re-teaching our Nation to prove what aspect of our history are being disregarded. I am a member of the Navajo Nation and a student at the University of New Mexico. 1 Out of respect for the values and beliefs of my family toward the use of the Navajo term for third-gender identity outside of cultural contexts, I will use the English term third-gender (TGI) in this paper and study. Diné Youth as Third-Gender Identifiers at the Dawn of the 21st Century 3 Introduction/ Background What if the next great Navajo medicine man is locked up in a closet somewhere? What if we’re the ones to heal our culture? What if we’re the ones to restore our religion? (Yurth, 2005). Estrada (2011) introduces Wesley Thomas, a Navajo third-gender identifier, who shares a postcolonial perspective of third-gender. According to Thomas and his teachings of Navajo thirdgender, he states that before colonization, our traditional perspective claims TGI’s “were herbalists. They were negotiators. They were healers. They were matchmakers. They counseled couples. And when children were orphaned, the third-gender identifiers would become the caretakers of the children” (p. 171). Thomas demonstrates that TGI’s were essential and played a large role in all Navajo families. Furthermore, TGI’s are noticed with accumulation of knowledge and controls of wealth. They are given special opportunities for acquisition of knowledge and are the essential center of all families. However, over time, the enculturation of Western ideology was growing among the Navajo people and negated the knowledge of traditional third-gender roles for many Navajo people. The Navajo Nation government was also being influenced by Western religion, primarily Christianity, and after the enactment of the Diné Marriage of 2005, many Navajo third-genders resented the Nation because this act defined marriage as between a male and female in Navajo Nation law. Researchers have looked at this historical atmosphere in regards to third-gender people, and others note the important conflicts that transitioned, causing the importance of cultural knowledge to be minimized. The clashes of traditional and contemporary knowledge have influenced a lot of societal interaction and thought, but the existence of traditionalism within third-genders’ interests and knowledge today is prevalent. In response to this clash, my research question: What influences cultural learning and Diné Youth as Third-Gender Identifiers at the Dawn of the 21st Century 4 knowledge among Diné youth with third-gender identities? – is an exciting topic I wanted to explore. I want to understand how third-genders today learn and perform traditional tasks, know the Navajo history and culture, and more importantly, speak the language. With limited sources regarding third-gender identifiers, this research is unique because it offers another perspective for understanding Navajo TGIs. As the lead investigator, my approach to this research is through an insider and outsider perspective. As a member of the Navajo Nation, I have been around third-genders and I feel I have an awareness of their characteristics or qualities of how they express their identity. The Navajo Nation is the largest Native American tribe and land base in the United States. According to the 2012 census, there are over 300,000 Navajo registered members. The region where the Navajo Nation is located consist of the states; New Mexico, Arizona and Utah. About three hours east of the mainland of the Navajo Nation is Albuquerque, New Mexico. The University of New Mexico is located in the center region of the city. The university has over 25,000 enrolled students. My participants will all be coming from the university as students. My participants will all be Navajos. The simple translation of TGI is a male homosexual, but in a traditional sense, we have a Navajo name. In a traditional sense and in Navajo language, they are referred to as thirdgender. Research Inquiry and Question With the limited research available that is dedicated to the topic of Navajo third-gender, it makes it easy to pinpoint the academic gaps. The sources talk about the historical concepts and themes associated with TGI’s, but to learn about the history alone calls into question the comparativeness it has with today’s society of third-genders. There are still third-genders today Diné Youth as Third-Gender Identifiers at the Dawn of the 21st Century 5 who fit the descriptions explained by the past research. They learn the cultural practices and speak the language. With the influences of colonization that still continues, Navajo TGI’s continue to practice and learn Navajo philosophy. In regards, the current life of today’s thirdgenders plus the re-teaching of its historical concepts of identity can shape more positivity among the Nation by minimizing societal problems and sending a message to our Nations government system. Thus my research question remains: What influences cultural learning and knowledge among Dine youth with third-gender identifiers? Purpose The purpose of this study is to grasp on the importance of answering my research question. Past studies have provided a historical overview of Navajo third-genders. These stories included the first two famous third-genders who lived on the Navajo Nation along with the benefits and richness of their lives; who they were, how they were perceived and the ways in which they practiced their everyday lives. As healers and matchmakers of the Navajo tribe, they were not reluctant because of their identity. They were revered for who they were; men who took on the roles of females. This was seen upon all third-genders. As time became unpredictable, Christianity and post-colonialism became an influence, reversing the thoughts of many traditional Navajos. As a result, third-genders were not accepted or viewed as a figure of wisdom and spirituality. Though these influences occurred, the revelation of today’s third-gender identifiers is noticeably described as what the researchers entailed; male men who cooked, wore woman’s clothing, and found interest in men. The explanation, however, behind this reverse teaching of third-gender is to promote wealth and acceptance in today’s society. Moreover, to establish a foundation that entails Diné Youth as Third-Gender Identifiers at the Dawn of the 21st Century 6 positivity with guidance for future generations. In an era where Native American cultures and languages are becoming extremely vital, it is important to conjure details in a tribe to help future generations. The proposed qualitative study will be exploratory and descriptive, providing an understanding of the thematic roles of my participants through interviews. As part of the study, 10 Navajo male who identify as third-gender at the University of New Mexico will elaborate on their experiences and knowledge regarding the historical and current politics of their identity in a traditional and contemporary conviction. My participants will be interviewed by audio and video recording, if permitted by the interviewee. After all the interviews have concluded, they will then be transcribed and formatted to give insight about the relativity based on the research question. This paper will also include a recommendations and implications section regarding what possibilities are there if we re-teach about third-genders. The responses from the interviews will create a positive atmosphere and good representation for all Diné third-genders. The current knowledge and lives of today’s third-gender identifiers can be renewed coming from an unhappy rejection caused from outsiders. The political implications will regard issues on the Navajo Nation which will be counted with their identity. Our Nation needs to know Navajo TGI’s also identify with four clans, just like everyone else. The interviews will also provide a significant amount of knowledge and experiences that will offer a positive perception to traditional oriented third-genders today. Review of the Literature The focus of my paper is Navajo third-genders, past and present. Although many tribes may have their own stories and cultures in regards to third-genders, but my study will be based Diné Youth as Third-Gender Identifiers at the Dawn of the 21st Century 7 on the Navajo way of life. Most of the professional and scholarly literature on Navajo thirdgender has focused on the four tenants of history, colonial influences, the political state of the Navajo Nation government and personal experiences. In Hill (1935), he discusses both genders as classes of privileged characters. Third-gender is introduced and associated with the accumulation and controls of wealth, are given special opportunities for its acquisition, and are the essential center of all families. Along with third-genders, Hill makes notification about transvestite and hermaphrodite, distinguishing the two, but noting that hermaphrodites were the real third-genders. The history and creation of third-gender is developed on the role of superiority within Navajo culture. Hill mentions in the first six third-genders for the Navajos but examines the famous two; Kla, from Newcomb, New Mexico and Kinipai from Buck’s Store, New Mexico. These men were male who aspired to lead their lives in the role of a woman. For Carolyn Epple (1998), it was about assessing what premises underlie the categories of berdache, 'alternate gender,' 'gay,' and 'two-spirit'; and whether these premises are relevant to the ways in which many Navajos construct the 'alternate gender' of those known as third-gender. Epple has spent several years with Navajo TGI’s, therefore, through a comparison and relationship analysis she hoped to gain an understanding of third-gender and other alternative third gender identifiers. The proponents of these categories often extricate traits from their identifiers and perceive male and female as genders and nothing more. In his article, Estrada (2011) critiques the film "Two Spirits," directed by Lydia Nibley, which discusses the discrimination of hate that Navajo TGI Fred Martinez underwent. Included are commentaries from other Native third-gender and the importance of how it connects to earth. The existence of equality and inclusion on humankind should remain important. Therfore, Estrada’s article explores the film's theme concerning the murder of Martinez. The film's Diné Youth as Third-Gender Identifiers at the Dawn of the 21st Century 8 depiction of the relationship between Navajo culture, religion and tradition and two spirit people is grasped. In addition, the article also frames around cultural, feminist, and gender activism and represents gazes as a unique reflection. In conclusion, Estrada also includes discrimination upon sexuality and the over analysis of third-gender through Martinez’s story. In a political sense, a column written in Indian Country Today (2005) shows the course of action taken within the judiciary branch of the Navajo Nation government concerning the Diné Marriage Act of 2005. The override passed the council with a vote of 62-12; with 12 delegates abstaining after President Dr. Joe Shirley vetoed the initial council vote, which was 67-0. The Navajo Nation Council was comprised of 88 delegates representing 110 chapters throughout the Navajo reservation. Subjects of the history and creation myth of third-gender people are proclaimed while Fort Defiance Councilman Larry Anderson also discussed briefly about the sovereignty of the future and that the decision was best suited in that purpose. In a short but significant commentary, Dan Begay, a Navajo TGI opposes the anti-same sex marriage initiative accepted by the Navajo Nation in Arizona in 2005. He provides his position of Navajo religion and tradition on homosexuality. This position is given through the role of gay people in Navajo culture, the relationship of same-sex marriage in some social problems and the acceptance he gained through his grandmother’s teachings. Yurth (2005), focuses on various Navajo third-gender Diné individuals. She includes Dr. Wesley Thomas’s insights about what third-gender is through a cultural context. Through this context are questions answered by various Navajo third-genders, who have been historically scarred as they grew up. They provide clear but different perspectives regarding family, cultural knowledge and Western influences. Some of the interviewees also refer back to the Navajo Nation Diné Marriage Act of 2005. In this commentary, the responses represent tradition, Diné Youth as Third-Gender Identifiers at the Dawn of the 21st Century 9 acculturation and, unfortunately, our ignorant Navajo Nation government system. Teles (a pseudonym), another Navajo TGI, lives in Phoenix, Arizona and shares his lifestyle and life in an interview led by Margaret A. Waller and Roland McAllen-Walker (2001). The article discusses the contemporary narrative theory as well as Navajo tradition of teaching through stories told by Teles. Under the course of family, appropriation of Native American sexualities, discontinuity between “coming out” theories and the Navajo worldview and the family construction of being gay and Navajo, Teles answers each component as it resonates with his life. Throughout the events and research topics in our Nations timeline, Navajo TGI’s remain prideful about their identities. They were considered privileged and culturally wealthy, and they were seen as a TGI, not isolated by male or female. Their identity is closely connected to Navajo spirituality. These TGI’s have secured a grandmother-grandson relationship that envelops them to expose their identity in a nonchalant manner. They explicitly share their opinions and create a sense of understanding for people who are around them. As people who were once revered, they still allow their voices to be proactive to our Nation, despite having small popularity. Many of them did not fall so easily as they continue to be comfortable with whom they are. It is easily to see an act of hopelessness, but for many TGI’s it was the camaraderie of their families and friends that kept them intact. Methodology The research plan will proceed under a strategy of inquiries constructed from a qualitative method. The strategy of inquiry derives from an Indigenous based research, more specifically, a Navajo centric phenomenological study. It is based on the fact that I am Diné Youth as Third-Gender Identifiers at the Dawn of the 21st Century 10 identifying through observation the male TGI community and their expressions of Navajo cultural knowledge and identity prone by large and proud extent. Each of my 10 participants will have the option, based on the consent form, whether they will have a pseudonym or their legal name. The interviews will immerse me with an understanding of their philosophical growth, that being openly TGI or not and how that resonates with their Navajo cultural knowledge and identity. A phenomenological approach is a study of a small number of subjects through extensive and prolonged engagements to develop patterns and relationships of meaning will be the themes of my interviews. The observational portion from the interviews will be based on the recording, if permitted by my participants. I believe in a complex topic, such as mine, discussions and stories will have deep sentimental meaning, which makes capturing the expressions of my participants important. It will provide additional help for me to understand the connections of their stories to the way they are feeling. For instance, a tear could imply joy in a story about an accomplishment verses a story about the loss of a loved one. A tear represents a strong feeling toward an emotion. Each of my participants will likely respond in a constructivist perspective. The statistical analysis from the study will be categorized from the interviews. The themes will be labeled and used to construct paragraphs dedicated to discussing the themes as they relate back to the research question. The themes, for example, if they all talk about how their families were accepting and traditionally dynamic, that will be discussed in several paragraphs, providing a positive life that was established for a child whose life could have been a lot worst. Prior to the interviews, a consent form will be discussed and signed by both my participant and I before my interview questions are asked. I have prepared a consent form that Diné Youth as Third-Gender Identifiers at the Dawn of the 21st Century 11 provides different options for my participant to feel comfortable. These options include, whether to be recorded or audio recorded, confirmation to share their responses, provide their names in potential publishing material, provide their responses in a classroom setting and used for only the purpose that it is intended for. For the formal format of the consent form, refer to Appendix II. To elucidate the tear example, video and audio recording will be active. The point is to have a word-for-word transcription that will help to categorize the themes to fit the research question. The video recording is to help support those categories through emotion and responsive expressions. Expressions will be a key aspect in this research because it provides evidence with the responses that are being given. Each of the interviews will take place in a quite location on the University campus. This will allow for no distractions by which the participants will be comfortable to speak openly about the questions. I will be selecting my participants based on my relationship with them. Since I will know these participants, it will not be too difficult to hear the full stories about their lives growing up. Asking a random person questions about their life, especially if they are third-gender will not produce significant results as oppose to someone you are know personally. Therefore, my participants will be close peers, classmates, or close friends. Each interview will vary depending on how in-depth the interview will be. Some may take longer than others. I have developed 13 questions for each of the participants. Along with those 13 questions will be following up questions. The questions will be in a thought-provoking manner. During the interviews they will be questioned in terms of clarification, elaboration, or substitution for any given response to the original questions. Research Site Diné Youth as Third-Gender Identifiers at the Dawn of the 21st Century 12 The site of my research will be at my apartment. This includes writing my paper, editing more drafts, looking at the interview questions and watching the video to abstract themes. Other than my interviews, the research will be progressing at the location of where I live unless I am meeting with a mentor or having available time on the university campus to look over some information. Theoretical Framework The theoretical framework is established based on my literature review. The sources that I have reviewed and analyzed form my framework. It will make clear the vast accumulation of influences in today’s society from expressed thoughts by the continuation of third-genders to know the Navajo history beyond those not identified as third-gender. The notion of politics in TGI communities will demonstrate the need to progress towards a traditional based governmental system. The thematic plausibility within each response will frame the study to be responsive and available. The extensive and prolong importance of TGIs will provide validity in our history. From these various sources, TGI is a traditional keen we must respect. Colonization still continues to influence TGIs causing various different identifiers, such as gay, queer, homosexual or as the derogatory slang “fag”, to overshadow the holy and spiritual connotation termed in Navajo. My research question is to gain an understanding about why current TGIs show interest in our Navajo language and culture. Through the sources presented, there are three key components that could be possible influences for TGIs to be the moderators of current Navajo philosophies and tradition. First, the history lesson is important because those who know our history tend to be understanding of where we come from and what to respect. Second, the relationship of family, Diné Youth as Third-Gender Identifiers at the Dawn of the 21st Century 13 especially grandmothers, shows a relief of acceptance and to feel more respectful towards elderly tradition, resulting in the continuation of learning and practicing. Their interest levels are perhaps superior because they listen to their grandmothers and find the culture to be extremely important. Lastly, the political awareness only makes it more important to challenge the Western mimicry of how the Navajo Nation government is maintaining their system. The feelings expressed towards the Diné Marriage Act of 2005 prove that TGIs are relatively cautious of their identity but not afraid to protect their teachings. The outcomes of these three components tie to the learning and living within the philosophical concept of Sa’2h Naagh17 Bik’eh Hózh=. The statistical analysis from the study will be to categorize the perspectives and ideas learned from the interviews into themes. The themes will be labeled and used to construct paragraphs dedicated to discussing the themes as they relate back to the research question. For example, one theme talks about how their families were accepting and traditionally dynamic, that will be discussed in several paragraphs in terms of how this influence (theme) nurtured a positive life that was established for a child whose life could have been a lot worse. Limitations The types of challenges I believe I will come across are getting my total number of participants. I feel 10 is an adequate number to grasp on themes and write accordingly. However, there may not be 10. If that is the case, I will work with the six participants I currently have who are willing to share their stories and be a part of my research. Though I have potential candidates, they uncertainty as whether I would be the person they do not mind sharing their lived history with is debatable. This will be resolved by dealing with the most participants available and continuing my study with them. Diné Youth as Third-Gender Identifiers at the Dawn of the 21st Century 14 Results The data that are collected will be categorized thematically. Each will be written about in paragraph form, discussing the commonalities related to the research question. Below is an example of the format and how it will be constructed with the themes, participatory responses as it coincides, the paragraph form, and finally the relationship to the research question. There will be no limit to the amount of themes detected from my participants. Themes Participant responses Paragraph(s) Relationship to RQ Significance/Implications This study is important because the Navajo Nation lacks recognition to the cultural importance of the hierarchy of genders. This hierarchy of identity for the Navajo Nation is identified with four identities. Dr. Wesley Thomas names these genders based from his knowledge, which I use in my paper. These genders are relinquished to an extent today but are engraved in the history of the Navajo people. The genders being, in order: first gender- female heterosexuals, then male heterosexuals, then male homosexuals, and lastly female homosexuals. TGI’s will provide adequate shared experiences and stories that will maintain the importance of Navajo culture and identity. Our elders have taught so many life lessons to their following generation, which remains repetitive. Within the timeline of the past century, we lost the value of who we are as people. Therefore, this study reminds the community that we ought to maintain the importance of the sacred lives within the communities of our reservation. The benefits of TGI’s will soon be resolved and their knowledge of our history and culture will continue to Diné Youth as Third-Gender Identifiers at the Dawn of the 21st Century 15 progress. The implications and recommendations is to use this study to re-teach in communities. For example, on January 27, 2013, the Navajo Nation hosted its first LGBTQ Symposium. This was the first time the Navajo Nation has had an event dedicated to the existence of third-genders. This research can be included in future symposiums as a way to not only remind, but discuss how these third-genders are still carrying the language and cultural practices. I think it would be great to share this research to people in the hopes that my work will not just be an extraction of truths, but provide information with which they can better control their lives and resources. This study with students from the University of New Mexico can be broadened into further research to more TGI’s from the Navajo Nation because I have witnessed the same cultural knowledge among TGI’s back on our reservation. Timeline/Plan of Work Months 1-3 Annotated Bibliography 4-6 7-9 X Literature Review X IRB Process X Research Proposal X IRB Approval X 1-5 Interviews X 6-10 Interviews X Transcriptions X Draft of Paper X 10-12 Diné Youth as Third-Gender Identifiers at the Dawn of the 21st Century Final Paper X 16 X I plan to be done with an adequate amount of my research that will enable the points I am trying to make within an 11 month time frame. University of New Mexico’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) will help to account my participants and allow me to have authority to proceed with my research on the university campus. After my papers are contently and concisely written, I plan to make presentations on my findings. This table illustrates my initial timeline for the progress I am planning to conclude my research. The right column indicated the main points I have to accomplish to fulfill the complete spectrum of my study. The months are represented by intervals of three, which will coincide with the requirements that I am taking for my study to be satisfyingly successful. Diné Youth as Third-Gender Identifiers at the Dawn of the 21st Century 17 Bibliography Begay, Dan. “Proud to be Navajo and Gay.” Echo Magazine 16.21 (2005): 14 Supplemental Index Epple, Carolyn. “Coming to Terms with Navajo ‘nádleehí’: A Critique of ‘berdache’, ‘Gay’, ‘Alternate Gender,’ and ‘Two Spirit.’” American Ethnologist 2 (1998): 267. JSTOR Arts and Sciences II. Estrada, Gabriel S. “Two Sprits, Nádleeh, and LGBTQ2 Navajo Gaze.” American Indian Culture and Research Journal 35.4 (2011): 167-190. Academic Research Complete. Hill, W. W. “The Status of the Hermaphrodite and Transvestite in Navaho Culture.” American Anthropologist 2 (1935): 273 JSTOR Arts and Sciences II. Nibley, Lydia, and Russell Martin. “Two Spirits” / A Production Of Say Yes Quickly ; A CoProduction Of Riding The Tiger, Just Media ; Directed By Lydia Nibley ; Produced By Russell Martin, Lydia Nibley ; Written By Russell Martin, Lydia Nibley. n.p.: New York, NY : Distributed by the Cinema Guild, c2009., 2009. “Same-Sex Marriage Ban Becomes Law”. Indian Country Today. Online Web. 13 June 2005. Walker, Margaret A. and McAllen-Walker, Roland. “One Man’s Story of Being Gay and Diné (Navajo): A Study in Resilience.” In Bernstein, M. & Reimann, R. (2001). Queer Families, Diné Youth as Third-Gender Identifiers at the Dawn of the 21st Century Queer Politics: Challenging Culture and The State (pp. 87-103). New York: Columbia University Press. Yurth, Cindy. “Modern-Day Nádleeh: GLBT Navajo Share Their Hopes and Struggles.”: The Navajo Times 27 November 2005. A1 Print. 18 Diné Youth as Third-Gender Identifiers at the Dawn of the 21st Century 19 Appendix I Interview Questions 1. First state your name, age, where you are from, and clarify your identity. 2. Have you told your parents or guardians about your identity? What is keeping you from telling them? 3. What is your families’ concept or belief of people who identity as third-gender? 3. How did you grow up among Navajo tradition within your family? 4. How were your parents, father and/or mother, reacting to your identity within a traditional context? 5. Do you participate in any traditional ceremonies, dances or participate in terms of helping and assisting at these events? 6. Within in your family, how has your success as an individual connecting to the way your family feels? 7. Could you explain, if any, any complications within your household about how you identify yourself? 8. Furthermore, could you explain how you grew up as a child within the education system? Provide both the good and bad as it resonated with your identity. 9. Is your maternal and paternal elders influencing your life as a third-gender, if so, may you elaborate? 10. What is your belief about third-gender identifiers and how do you think Navajo society should treat those who identify as third-gender? Name the utmost significances? 12. What are some of your experiences, past and current, about relating to your peers, colleagues, or family members in terms of having a distinction about third-gender identity and heterosexuality? 13. What are some of the influences in your life about the traditional and philosophical concepts that embodies language, culture, knowledge, and other traditional teachings that have been carrying your strength? Diné Youth as Third-Gender Identifiers at the Dawn of the 21st Century 20 Appendix II CONSENT FORM I,________________________, agree to participate in as a willing consultant in the University of New Mexico McNair Program research project conducted by _________________________ on ____________, 2013. I understand that this session will be audio recorded, and that I may request that the recorder be turned off at any time, for any reason. I understand that this session will also be video recorded, and that I may request that the recorder be turned off at any time, for any reason. I understand that the recordings will only be for the conductor and his mentor, but they will not be further distributed without my permission. I do / do not give permission for audio recordings to be made. I do / do not give permission for video recordings to be made. I do / do not wish to remain anonymous in all materials produced as the result of this fieldwork. I understand that if I choose to be anonymous, all effort will be made to respect this wish but complete anonymity cannot be guaranteed. I want to be referred to as ___________________ for my pseudo name. I do / do not give permission for primary materials (field notes, audio and video recordings) to be made available to others. I do / do not give permission for secondary materials (such as academic papers giving analyses of the language) to be made available to others, or published on the internet or in print. I do / do not wish to be informed before language materials collected in the study are used for a purpose other than that for which they were originally intended. Signed by consultant: Date: Signed by participant: Date: Signed by mentor: Diné Youth as Third-Gender Identifiers at the Dawn of the 21st Century Date: Each signee is to receive a copy of this consent form. 21