answer 3

advertisement

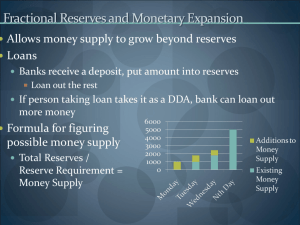

5 marks 1.Arguments The main functions of the central bank are to maintain low inflation and a low level of unemployment, although these goals are sometimes in conflict (according to Phillips curve). A central bank may attempt to do this by artificially influencing the demand for goods by increasing or decreasing the nation's money supply (relative to trend), which lowers or raises interest rates, which stimulates or restrains spending on goods and services. An important debate among economists in the second half of the twentieth century concerned the central bank's ability to predict how much money should be in circulation, given current employment rates and inflation rates. Economists such as Milton Friedman believed that the central bank would always get it wrong, leading to wider swings in the economy than if it were just left alone.[38] This is why they advocated a non-interventionist approach—one of targeting a pre-specified path for the money supply independent of current economic conditions— even though in practice this might involve regular intervention with open market operations (or other monetary-policy tools) to keep the money supply on target. The Chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve, Ben Bernanke, has suggested that over the last 10 to 15 years, many modern central banks have become relatively adept at manipulation of the money supply, leading to a smoother business cycle, with recessions tending to be smaller and less frequent than in earlier decades, a phenomenon termed "The Great Moderation"[39] This theory encountered criticism during the global financial crisis of 2008–2009[citation needed]. Furthermore, it may be that the functions of the central bank may need to encompass more than the shifting up or down of interest rates or bank reserves[citation needed]: these tools, although valuable, may not in fact moderate the volatility of money supply (or its velocity)[citation needed]. 2.Money supplies around the world Components of US money supply (currency, M1, M2, and M3) since 1959. In January 2007, the amount of "central bank money" was $750.5 billion while the amount of "commercial bank money" (in the M2 supply) was $6.33 trillion. M1 is currency plus demand deposits; M2 is M1 plus time deposits, savings deposits, and some money-market funds; and M3 is M2 plus large time deposits and other forms of money. The M3 data ends in 2006 because the federal reserve ceased reporting it. Components of the euro money supply 1998–2007 See also: Money supply Fractional-reserve banking determines the relationship between the amount of "central bank money" in the official money supply statistics and the total money supply. Most of the money in these systems is "commercial bank money". Fractional-reserve banking allows the creation of commercial bank money, which increases the money supply through the deposit creation multiplier. The issue of money through the banking system is a mechanism of monetary transmission, which a central bank can influence indirectly by raising or lowering interest rates (although banking regulations may also be adjusted to influence the money supply, depending on the circumstances). This table gives an outline of the makeup of money supplies worldwide. Most of the money in any given money supply consists of commercial bank money.[16] The value of commercial bank money is based on the fact that it can be exchanged freely at a bank for central bank money. [16][17] The actual increase in the money supply through this process may be lower, as (at each step) banks may choose to hold reserves in excess of the statutory minimum, borrowers may let some funds sit idle, and some members of the public may choose to hold cash, and there also may be delays or frictions in the lending process.[22] Government regulations may also be used to limit the money creation process by preventing banks from giving out loans even though the reserve requirements have been fulfilled. [23] 3.Effects on money supply The reserve requirement can be used as an instrument of monetary policy, because the higher the reserve requirement is set, the less funds banks will have to loan out, leading to lower money creation and perhaps ultimately to higher purchasing power of the money previously in use. The effect is multiplied, because money obtained as loan proceeds can be re-deposited; a portion of those deposits may again be loaned out, and so on. The effect on the money supply is governed by the following formulas: : definitional relationship between monetary base Mb (bank reserves plus currency held by the non-bank public) and the narrowly defined money supply, M1, : derived formula for the money multiplier mm, the factor by which lending and re-lending leads M1 to be a multiple of the monetary base, where notationally, the currency ratio: the ratio of the public's holdings of currency (undeposited cash) to the public's holdings of demand deposits; and the total reserve ratio ( the ratio of legally required plus non-required reserve holdings of banks to demand deposit liabilities of banks). However, in the United States (and other countries except Brazil, China, India, Russia), the reserve requirements are generally not frequently altered to implement monetary policy because of the short-term disruptive effect on financial markets. 20 marks 1.Money creation by the central bank Main article: Monetary policy Within almost all modern nations, special institutions exist (such as the Federal Reserve System in the United States, the European Central Bank (ECB), and the People's Bank of China) which have the task of executing the monetary policy and often acting independently of theexecutive. In general, these institutions are called central banks and often have other responsibilities such as supervising the smooth operation of the financial system. There are several monetary policy tools available to a central bank to expand the money supply of a country: decreasing interest rates by fiat; increasing the monetary base; and decreasing reserve requirements. All have the effect of expanding the money supply. The primary tool of monetary policy is open market operations. This entails managing the quantity of money in circulation through the buying and selling of various financial assets, such as treasury bills, government bonds, or foreign currencies. Purchases of these assets result in currency entering market circulation (while sales of these assets remove money from circulation). Usually, the short term goal of open market operations is to achieve a specific short term interest rate target. In other instances, monetary policy might instead entail the targeting of a specific exchange rate relative to some foreign currency, the price of gold, or indices such as Consumer Price Index. For example, in the case of the USA the Federal Reserve targets the federal funds rate, the rate at which member banks lend to one another overnight. The other primary means of conducting monetary policy include: (i) Discount window lending (as lender of last resort); (ii) Fractional deposit lending (changes in the reserve requirement); (iii) Moral suasion (cajoling certain market players to achieve specified outcomes); (iv) "Open mouth operations" (talking monetary policy with the market). The conduct and effects of monetary policy and the regulation of the banking system are of central concern to monetary economics. Quantitative easing Main article: Quantitative easing Quantitative easing involves the creation of a significant amount of new base money by a central bank by the buying of assets that it usually does not buy. Usually, a central bank will conduct open market operations by buying short-term government bonds or foreign currency. However, during a financial crisis, the central bank may buy other types of financial assets as well. The central bank may buy long-term government bonds, company bonds, asset backed securities, stocks, or even extend commercial loans. The intent is to stimulate the economy by increasing liquidity and promoting bank lending, even when interest rates cannot be pushed any lower. Quantitative easing increases reserves in the banking system (i.e. deposits of commercial banks at the central bank), giving depository institutions the ability to make new loans. Quantitative easing is usually used when lowering the discount rate is no longer effective because interest rates are already close to or at zero. In such a case, normal monetary policy cannot further lower interest rates, and the economy is in a liquidity trap. Physical currency In modern economies, relatively little of the supply of broad money is in physical currency. For example, in December 2010 in the U.S., of the $8853.4 billion in broad money supply (M2), only $915.7 billion (about 10%) consisted of physical coins and paper money. [2] The manufacturing of new physical money is usually the responsibility of the central bank, or sometimes, the government's treasury. Contrary to popular belief, money creation in a modern economy does not directly involve the manufacturing of new physical money, such as paper currency or metal coins. Instead, when the central bank expands the money supply through open market operations (e.g. by purchasing government bonds), it credits the accounts that commercial banks hold at the central bank (termedhigh powered money). Commercial banks may draw on these accounts to withdraw physical money from the central bank. Commercial banks may also return soiled or spoiled currency to the central bank in exchange for new currency.[3] 2.Money creation through the fractional reserve system Main article: Fractional-reserve banking Through fractional-reserve banking, the modern banking system expands the money supply of a country beyond the amount initially created by the central bank.[4] There are two types of money in a fractionalreserve banking system, currency originally issued by the central bank, and bank deposits at commercial banks:[5][6] 1. central bank money (all money created by the central bank regardless of its form, e.g. banknotes, coins, electronic money) 2. commercial bank money (money created in the banking system through borrowing and lending) - sometimes referred to as checkbook money[7] When a commercial bank loan is extended, new commercial bank money is created. As a loan is paid back, more commercial bank money disappears from existence. Since loans are continually being issued in a normally functioning economy, the amount of broad money in the economy remains relatively stable. Because of this money creation process by the commercial banks, the money supply of a country is usually a multiple larger than the money issued by the central bank; that multiple is determined by the reserve ratio or other financial ratios (primarily the capital adequacy ratio that limits the overall credit creation of a bank) set by the relevant banking regulators in the jurisdiction. Re-lending An early table, featuring reinvestment from one period to the next and a geometric series, is found in the tableau économique of the Physiocrats, which is credited as the "first precise formulation" of such interdependent systems and the origin of multiplier theory.[8] Money multiplier Main article: Money multiplier The expansion of $100 through fractional-reserve lending under the re-lending model of money creation, at varying rates. Each curve approaches a limit. This limit is the value that the money multipliercalculates. Note that the top amount resulting in $1000 is not 20% but 10% as 100/0.1=1000. The most common mechanism used to measure this increase in the money supply is typically called the money multiplier. It calculates the maximum amount of money that an initial deposit can be expanded to with a given reserve ratio – such a factor is called a multiplier. As a formula, if the reserve ratio is R, then the money multiplier m is the reciprocal, and is the maximum amount of money commercial banks can legally create for a given quantity of reserves. In the re-lending model, this is alternatively calculated as a geometric series under repeated lending of a geometrically decreasing quantity of money: reserves lead loans. In endogenous money models, loans lead reserves, and it is not interpreted as a geometric series. In practice, because banks often have access to lines of credit, and the money market, and can use day time loans from central banks, there is often no requirement for a pre-existing deposit for the bank to create a loan and have it paid to another bank.[9][10] The money multiplier is of fundamental importance in monetary policy: if banks lend out close to the maximum allowed, then the broad money supply is approximately central bank money times the multiplier, and central banks may finely control broad money supply by controlling central bank money, the money multiplier linking these quantities; this was the case in the United States from 1959 through September 2008. If, conversely, banks accumulate excess reserves, as occurred in such financial crises as the Great Depression and theFinancial crisis of 2007–2010 – in the United States since October 2008, then this equality breaks down, and central bank money creation may not result in commercial bank money creation, instead remaining as unlent (excess) reserves.[11] However, the central bank may shrink commercial bank money by shrinking central bank money, since reserves are required – thus fractionalreserve money creation is likened to a string, since the central bank can always pull money out by restricting central bank money, hence reserves, but cannot always push money out by expanding central bank money, since this may result in excess reserves, a situation referred to as "pushing on a string". 3.Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 On October 3, 2008, Section 128 of the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 allowed the Fed to begin paying interest on excess reserve balances as well as required reserves. They began doing so three days later.[3] Banks had already begun increasing the amount of their money on deposit with the Fed at the beginning of September, up from about $10 billion total at the end of August, 2008, to $880 billion by the end of the second week of January, 2009.[4][5] In comparison, the increase in reserve balances reached only $65 billion after September 11, 2001 before falling back to normal levels within a month. Former U.S. Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson's original bailout proposal under which the government would acquire up to $700 billion worth of mortgage-backed securities contained no provision to begin paying interest on reserve balances.[6] The day before the change was announced, on October 7, Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke expressed some confusion about it, saying, "We're not quite sure what we have to pay in order to get the market rate, which includes some credit risk, up to the target. We're going to experiment with this and try to find what the right spread is."[7] The Fed adjusted the rate on October 22, after the initial rate they set October 6 failed to keep the benchmark U.S. overnight interest rate close to their policy target, [7][8] and again on November 5 for the same reason.[9] The Congressional Budget Office estimated that payment of interest on reserve balances would cost the American taxpayers about one tenth of the present 0.25% interest rate on $800 billion in deposits: Estimated Budgetary Effects[10] Year Millions of dollars 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 0 -192 -192 -202 -212 -221 -242 -253 -266 -293 -308 (Negative numbers represent expenditures; losses in revenue not included.) 0.25% simple interest on $800 billion is $2 billion, not $202 million as shown for 2009. But those expenditures pale in comparison to the lost tax revenues worldwide resulting from decreased economic activity from damage to the short-term commercial paper and associated credit markets. Beginning December 18, the Fed directly established interest rates paid on required reserve balances and excess balances instead of specifying them with a formula based on the target federal funds rate.[11][12][13] On January 13, Ben Bernanke said, "In principle, the interest rate the Fed pays on bank reserves should set a floor on the overnight interest rate, as banks should be unwilling to lend reserves at a rate lower than they can receive from the Fed. In practice, the federal funds rate has fallen somewhat below the interest rate on reserves in recent months, reflecting the very high volume of excess reserves, the inexperience of banks with the new regime, and other factors. However, as excess reserves decline, financial conditions normalize, and banks adapt to the new regime, we expect the interest rate paid on reserves to become an effective instrument for controlling the federal funds rate."[14] Also on January 13, Financial Week said Mr. Bernanke admitted that a huge increase in banks' excess reserves is stifling the Fed's monetary policy moves and its efforts to revive private sector lending.[15] On January 7, 2009, the Federal Open Market Committee had decided that, "the size of the balance sheet and level of excess reserves would need to be reduced."[16] On January 15,Chicago Fed president and Federal Open Market Committee member Charles Evans said, "once the economy recovers and financial conditions stabilize, the Fed will return to its traditional focus on the federal funds rate. It also will have to scale back the use of emergency lending programs and reduce the size of the balance sheet and level of excess reserves. Some of this scaling back will occur naturally as market conditions improve on account of how these programs have been designed. Still, financial market participants need to be prepared for the eventual dismantling of the facilities that have been put in place during the financial turmoil" [17] At the end of January, 2009, excess reserve balances at the Fed stood at $793 billion [18] but less than two weeks later on February 11, total reserve balances had fallen to $603 billion. On April 1, reserve balances had again increased to $806 billion, and on February 10, 2010, they stood at $1.154 trillion. By August 2011, they reached $1.6 trillion.[19] 4.History In 1924, Senator James Couzens (Michigan) introduced a resolution in the Senate for the creation of a Select Committee to investigate the Bureau of Internal Revenue. At the time, there were reports of inefficiency and waste in the Bureau and allegations that the method of making refunds created the opportunity for fraud. One of the issues investigated by the Select Committee was the valuation of oil properties. The Committee found that there appeared to be no system, no adherence to principle, and a total absence of competent supervision in the determination of oil property values. In 1925, after making public charges that millions of tax dollars were being lost through the favorable treatment of large corporations by the Bureau, Senator Couzens was notified by the Bureau that he owed more than $10 million in back taxes. Then Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon was believed to be personally responsible for the retaliation against Senator Couzens. At the time, Secretary Mellon was the principal owner of Gulf Oil, which had benefited from rulings specifically criticized by Senator Couzens. The investigations by the Senate Select Committee led, in the Revenue Act of 1926, to the creation of the Joint Committee on Internal Revenue Taxation. The select committee emphasized the need for the institution of a procedure by which the Congress could be better advised as to the systems and methods employed in the administration of the internal revenue laws with a view to the needs for legislation in the future, simplification and clarification of administration, and generally a closer understanding of the detailed problems with which both the taxpayer and the Bureau of Internal Revenue are confronted. It is more properly the function of the Senate Finance Committee and the House Ways and Means Committee, jointly, to engage in such an activity.(2) As originally conceived by the House, a temporary "Joint Commission on Taxation" was to be created to "investigate and report upon the operation, effects, and administration of the Federal system of income and other internal revenue taxes and upon any proposals or measures which in the judgment of the Commission may be employed to simplify or improve the operation or administration of such systems of taxes.....".(1) The Senate expanded significantly the functions contemplated by the House and transformed the proposed Joint Commission to a Joint Committee with a permanent staff. The Senate version was incorporated into the Revenue Act of 1926 and the Joint Committee was created.(3) The first Chief of Staff of the Joint Committee on Internal Revenue Taxation was L.H. Parker, who had been the chief investigator on Senator Couzens' Select Senate Committee. The Revenue Act of 1926 required the Joint Committee on Internal Revenue Taxation to publish from time to time for public examination and analysis proposed measures and methods for the simplification of internal revenue taxes and required the Joint Committee to provide a written report to the House and Senate by December 31, 1927, with such recommendations as it deemed advisable. The Joint Committee published its initial report on November 15, 1927, and made various recommendations to simplify the federal tax system, including a recommendation for the restructuring of the federal income tax title. In the Revenue Act of 1928, the Joint Committee's authority was extended to the review of all refunds or credits of any income, war-profits, excess-profits, or estate or gift tax in excess of $75,000. In addition, the Act required the Joint Committee to make an annual report to the Congress with respect to such refunds and credits, including the names of all persons and corporations to whom amounts are credited or payments are made, together with the amounts credit or paid to each. Since 1928, the threshold for review of large tax refunds has been increased from $75,000 to $2 million in various steps and the taxes to which such review applies has been expanded. Other than that, the Joint Committee's responsibilities under the Internal Revenue Code have remained essentially unchanged since 1928. While the statutory mandate of the Joint Committee has not changed significantly, the tax legislative process, however, has.