Chapter 11

advertisement

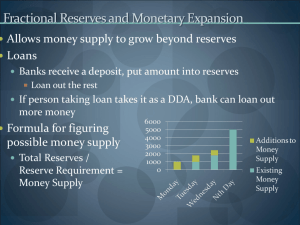

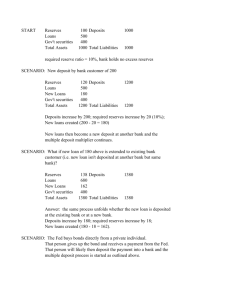

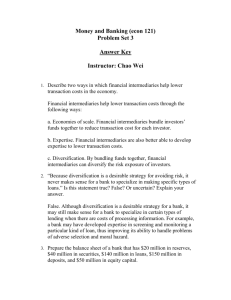

Money and the monetary system Definition of money Money is any commodity or token that is generally accepted as a means of payment. Money is an institution human societies devised to reduce transaction costs. Money performs three vital functions: Medium of exchange Unit of account Store of value Medium of exchange: If our economy did not use money, all transactions would have to take place by barter. This means that goods and services would be exchanged directly for other goods and services. Barter requires a double coincidence of wants. Unit of account: This means that the prices of goods and services are expressed in terms of the monetary unit, which significantly reduces the number of relative prices we need to deal with and therefore reduces transaction costs. Store of value: Because money can be held and exchanged later for goods and services, it may be held for spending at some later date. When it is held in this way, it is a store of value, or store of wealth. Forms of money The earliest money was commodity money. Many different commodities have been used as a medium of exchange, but gold and silver have always had an appeal because they have remained stable in value over long periods of time and relatively small quantities have had sufficient value to be used for most ordinary exchanges. Money further developed with the introduction of paper money that could be redeemed, i.e., exchanged, for specific quantities of metal at banking institutions. When paper money is redeemable for specific quantities of a commodity, the monetary system is said to be based on a commodity standard. Our modern paper money is fiat money, which is non-redeemable money established by law (“fiat” means “decree”). In a modern economy, most financial transactions do not involve either coins or paper money: payments are made by the transfer of funds that are on deposit in depository institutions, called checkable deposits. Money in the United States Coins in the U.S. originally contained their face value’s worth of metal (either gold or silver) and for this reason were known as full bodied coins, but our modern coins are token coins. The paper money in the U.S. consists of Federal Reserve Notes issued by the Federal Reserve System. The Federal Reserve System, or Fed, is the central bank of the United States. A central bank is a public authority that provides banking services to the banks, regulates financial institutions and markets and, most importantly, supplies money to the economy and regulates the money supply. Currency, coin and checkable deposits are highly liquid assets. Liquid assets are assets that may be turned into the means of payment rapidly, at low cost and without capital loss. Illiquid assets are assets that are difficult or costly to change into the means of payment, particularly if the change is likely to result in a capital loss. The Federal Reserve maintains statistics for several different definitions of the money supply. Money Supply M1: The narrowest and most liquid definition, M1, is currency and coin in circulation among the public, i.e., not in banks’ vaults, and checkable deposits owned by individuals and businesses and traveler’s checks. Money Supply M2 M2, which is broader and includes somewhat less liquid assets, is M1 plus savings deposits, small time deposits (less than $100,000), money market mutual funds and money market deposits. Structure of the Federal Reserve System There are 12 Federal Reserve districts and each has a district Federal Reserve Bank (FRB). Each district’s FRB has nine directors. The nine directors of each FRB appoint the FRB’s president. Functions of the FRBs: serving as a clearing house for checks between banks withdrawing damaged currency from circulation and issuing new currency making discount loans to banks in their districts regulating banks collecting data and doing research on business conditions in their districts Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System: There are seven governors, each appointed by the President of the United States and confirmed by the U.S. Senate. The governors serve nonrenewable 14-year terms. The chairman of the Board of Governors (currently Ben Bernanke) is chosen by the President of the United States from among the seven governors. The chairman serves a four-year renewable term. The Board of Governors sets reserve requirements for commercial banks and determines the discount rate charged by the FRBs for discount loans to commercial banks. The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC): The FOMC consists of the seven members of the Board of Governors, the president of the FRB of New York, and four other FRB presidents on a rotating basis. The chairman of the Board of Governors also chairs the FOMC. The FOMC determines the conduct of open market operations, the buying and selling of government securities in the bond market, which, as we will see, is the most important instrument used by the Fed to regulate the money supply and interest rates. Money creation and control Because the Fed’s ability to control the supply of money to the economy works through the banking system, we begin by examining a simplified balancesheet of a commercial bank: Assets Reserves cash deposits with Fed Loans Securities Liabilities Deposits Borrowings A deposit of, say, $100 by a member of the public in a bank has the following effect on the bank’s balance sheet: Assets Reserves +$100 Liabilities Deposits +$100 A loan of $100 by the bank to a member of the public has the following effect on the bank’s balance sheet: Assets Loans +$100 Liabilities Deposits +$100 The bank makes a loan by crediting the borrower’s checking account by the amount of the loan, i.e., by adding $100 to the balance in the borrower’s deposit account held with the bank. For every additional dollar of bank lending, bank deposits are increased by a dollar. Lending does not deplete reserves. Reserves are unaffected. Rather, it creates new deposits out of thin air! This represents an increase in the money supply, M1, because checkable deposits are part of M1. Bank lending creates new money. Now we turn to the Fed’s balance sheet: Monetary base Assets Liabilities Government securities Discount loans Currency in circulation Reserves Reserves are divided into: required reserves, which the banks are required by the Fed to hold, defined as a percentage of the banks’ total deposit liability to the public; and excess reserves, which are additional reserves the banks might choose to hold. Currency in circulation plus reserves are the monetary base of the economy. The monetary base is also called high-powered money because increases in it will, as we shall see, lead to multiple increases in the money supply, everything else held constant. Even a small change in the monetary base has a magnified effect on total deposits and hence on the money supply: Money supply Monetary base Reserves in the banking system are only a fraction of total deposits. This is made possible by the fact that deposits are created out of thin air as a consequence of bank lending. If the reserve requirement ratio, for example, is 10%, then each $1 of reserves potentially supports $10 of deposits, i.e., a $1 increase in reserves (monetary base) produces a $10 increase in deposits and hence in the overall money supply. Therefore a large money supply rests on a small monetary base. Control of the monetary base If the Fed wants to increase or decrease the money supply, all it has to do is increase or decrease the monetary base. The main way in which the Fed brings about changes in the monetary base is by altering the amount of reserves in the banking system through open market operations, which consist of either open market purchases, which are purchases of government securities – U.S. Treasury bonds – by the Fed in the bond market or open market sales, which are sales of government securities by the Fed. An open market purchase Suppose that the Fed purchases $100 of government securities from a bank: Banking system Assets Liabilities Reserves +$100 Securities -$100 The same transaction is shown on the Fed’s balance sheet as follows: Fed Assets Government securities +$100 Liabilities Reserves +$100 The net result is that reserves have increased by $100. Because there has been no change in currency, the monetary base has also increased by $100 (recall that monetary base = currency + reserves). Now let’s suppose, more realistically, that the Fed buys the $100 of government securities not from the banks but from a member of the nonbank public. To pay for the securities, the Fed issues a check, drawn on itself, for $100. Suppose that the member of the public who receives the check deposits it in an account at a bank: Banking system Assets Reserves Liabilities +$100 Deposits +$100 The effect on the Fed’s balance sheet is as follows: Fed Assets Securities +$100 Liabilities Reserves +$100 Again, the net result of a $100 open market purchase from a member of the nonbank public is a $100 increase in reserves and the monetary base, the same result that occurred when the Fed purchased the securities directly from the banks. Thus we can conclude that an open market purchase causes an increase in the monetary base by the same amount as the amount of the open market purchase. An open market sale Suppose that the Fed sells $100 of government securities and the securities are bought by one of the banks in the banking system. Banking system Assets Reserves -$100 Securities +$100 Liabilities The effect of the open market sale on the Fed’s balance sheet is as follows: Fed Assets Securities Liabilities -$100 Reserves -$100 The net result is that reserves have decreased by $100. Because there has been no change in currency, the monetary base has also decreased by $100. Thus we can conclude that an open market sale causes a decrease in the monetary base by the same amount as the amount of the open market sale. Discount loans In addition to open market operations, the Fed can also increase reserves in the banking system, and hence increase the monetary base, by making discount loans to the banks. A $100 discount loan to a bank: Banking system Assets Reserves +$100 Liabilities Discount loan from Fed +$100 Fed Assets Discount loan +$100 Liabilities Reserves +$100 The monetary base has increased by $100. We can conclude that if the volume of discount lending increases, the monetary base increases; if the volume of discount lending decreases, the monetary base decreases. Normally banks do not borrow from the Fed but prefer to borrow reserves from each other in an overnight interbank lending market called the federal funds market. The interest rate prevailing in this market is called the federal funds rate. The Fed’s open market operations affect the federal funds rate: Open market purchases increase the supply of bank reserves and therefore cause a decrease in the market equilibrium federal funds rate. Open market sales decrease the supply of bank reserves and therefore cause an increase in the market equilibrium federal funds rate. In fact, the Fed normally announces its monetary policy by stating a target for the federal funds rate. Changes in the federal funds rate, which is the basic cost of funds to the banks, then affect all other short term interest rates. A simple model of multiple deposit creation We have seen that the Fed supplies reserves to the banking system. Under fractional reserve banking, any increase in bank reserves supplied by the Fed brings about an even bigger increase in bank deposits created through bank lending, a response known as multiple deposit creation. Any increase in reserves, whether created through an open market purchase or through a discount loan, will enable the banks to increase their lending and deposits and thus expand the money supply. Suppose the Fed purchases $100 of government securities from Bank A. The effect of this open market purchase on Bank A and on the Fed is as follows: Bank A Assets Liabilities Reserves +$100 Securities -$100 Fed Assets Securities +$100 Liabilities Reserves +$100 What does Bank A do with its $100 of new reserves? Assume: the banks do not wish to hold excess reserves, above and beyond the amount of reserves they are required to hold, members of the nonbank public deposit all of the proceeds of loans in deposit accounts and do not hold any portion in currency, i.e., there is no currency drain of newly created deposits out of the banking system, the reserve requirement ratio, the ratio of required reserves to deposit liability which is dictated by the Fed, is 10%. Presumably, before the injection of $100 of new reserves, Bank A was holding an amount of reserves that was exactly equal to 10% of its deposit liability. Now that Bank A has received $100 of new reserves, without any change in its deposit liability, it must be the case that the entire $100 is excess reserves. By increasing its lending, Bank A can use up its excess reserves. But how much will it lend? If it lends less than $100, it will still have some excess reserves, which is contrary to our assumption that the banks do not wish to hold excess reserves. It will be extremely dangerous for the bank to lend more than $100, however, because, as we shall see, there is always the possibility that the proceeds of the loan might clear to a different bank, in which case Bank A will lose reserves equal to the amount of the loan. Therefore it follows that the maximum amount that Bank A can lend is the amount it can afford to lose, i.e., the amount of its excess reserves. Bank A will make a loan equal to its excess reserves, i.e., a loan of $100. Combining the effects of the $100 open market purchase by the Fed with the $100 loan on a single balance sheet gives the following: Bank A Assets Reserves +$100 Loans +$100 Securities -$100 Liabilities Deposits +$100 But now assume that the customer who borrowed $100 from Bank A writes a check in that amount and pays it to another individual who deposits it in his or her deposit account in Bank B. When the Fed clears the funds from Bank A to Bank B, Bank A’s balance-sheet position will be as follows: Bank A Assets Liabilities Reserves +$100 -$100 $0 Loans +$100 Securities -$100 Deposits +$100 -$100 $0 When the check clears, Bank B receives a new deposit of $100 and new reserves of $100. Bank B’s balance sheet changes as follows: Bank B Assets Reserves +$100 Liabilities Deposits +$100 By how much have Bank B’s excess reserves increased? Although Bank B’s total reserves have increased by $100, its excess reserves are $90, because it is required to hold reserves equal to 10% of $100, i.e., $10, in fulfillment of the reserve requirement for its new deposit liability of $100. Again the same rule applies to Bank B as applied previously to Bank A: The maximum amount by which Bank B can increase its lending is the amount of its excess reserves, which is $90, because this is the amount that Bank B can afford to lose if the loan proceeds should clear to another bank. Bank B’s balance sheet changes as follows: Bank B Assets Reserves +$100 Loans +$90 Liabilities Deposits +$100 +$90 +$190 But now assume that the customer who borrowed $90 from Bank B writes a check in that amount and pays it to another individual who deposits it in his or her deposit account in Bank C. When the Fed clears the funds from Bank B to Bank C, Bank B’s balance-sheet position will be as follows: Bank B Assets Liabilities Reserves +$100 -$90 +$10 Loans +$90 Deposits +$100 +$90 -$90 +$100 When the check clears, Bank C receives a new deposit of $90 and new reserves of $90. Bank C’s balance sheet changes as follows: Bank C Assets Reserves Liabilities +$90 Deposits +$90 By how much have Bank C’s excess reserves increased? Although Bank C’s total reserves have increased by $90, its excess reserves are $81, because it is required to hold reserves equal to 10% of $90, i.e., $9, in fulfillment of the reserve requirement for its new deposit liability of $90. Again the same rule applies to Bank C as applied previously to Banks A and B: The maximum amount by which Bank C can increase its lending is the amount of its excess reserves, which is $81, because this is the amount that Bank C can afford to lose if the loan proceeds should clear to another bank. Bank C’s balance sheet changes as follows: Bank C Assets Reserves Loans Liabilities +$90 +$81 Deposits +$90 +$81 +$171 But now assume that the customer who borrowed $81 from Bank C writes a check in that amount and pays it to another individual who deposits it in his or her deposit account in Bank D. When the Fed clears the funds from Bank C to Bank D, Bank C’s balance-sheet position will be as follows: Bank C Assets Reserves Loans Liabilities +$90 -$81 +$9 +$81 Deposits +$90 +$81 -$81 +$90 And so on … Clearly there is a pattern here: each successive bank creates loans and hence deposits equal to 90 percent of its newly-acquired reserves, the other 10 percent being required reserves. These newly-created deposits then clear to the next bank as reserves, and this bank then increases loans and deposits by 90 percent of this amount, etc. Each bank is effectively creating new money because each loan results in a new deposit at the next bank. If all banks make loans equal to the increase in their excess reserves, then the multiple expansion of deposits is illustrated in the following table: Bank Increase in deposits A B C D E F . . . $0 $100 $90 $81 $72.90 $65.61 . . . ________ $1,000.00 Total Increase in loans $100 $90 $81 $72.90 $65.61 $59.05 . . . ________ $1,000.00 Increase in reserves $0 $10 $9 $8.10 $7.29 $6.56 . . . _________ $100.00 For the whole banking system, the increase in reserves is $100 and the increase in deposits is $1,000. Thus, the increase in deposits is ten times the increase in reserves. This number 10 is called the deposit multiplier. It is the number that tells us the amount of deposits that can be supported by a given amount of reserves, or, in other words, it is the number that we multiply a change in reserves by to find the resulting change in deposits. Deposits = Deposit multiplier X Reserves. (“” means “change in”) In our example, Reserves = $100 and the multiplier = 10. Therefore: $1,000 = 10 X $100. The deposit multiplier is the reciprocal of the reserve requirement ratio, i.e., Deposit multiplier = 1 _________________________ . Reserve requirement ratio In our example, the reserve requirement ratio is 0.10. Therefore the deposit multiplier is: 1 _____ 0.10 = 10. How do we know that the deposit multiplier is the reciprocal of the reserve requirement ratio? If the banks do not hold excess reserves, then, R = rD X D, where R = Reserves E.g., $100 = 0.10 X $1,000. rD = Reserve requirement ratio D = Deposits. Dividing both sides by rD, 1 D = ___ rD X R. Taking the change () in both sides, D 1 = ___ rD X R. i.e., Deposits = Deposit multiplier X Reserves. In our example, R = $100, rD = 0.10, therefore, D = 1 ____ 0.10 X $100 = 10 X $100 = $1,000. We can summarize the effects of the $100 open market purchase with a single balance sheet for the entire banking system: Banking system Assets Reserves Loans Securities Liabilities +$100 +$1,000 -$100 Deposits +$1,000 Note that each individual bank can only create deposits equal to its excess reserves, but the banking system as a whole can generate a multiple expansion of deposits. By changing the reserve requirement ratio, the Fed can change the deposit multiplier and thus bring about an increase or decrease in total bank deposits and hence in the overall money supply. If the Fed raises the reserve requirement ratio, for example, the deposit multiplier will decrease, which means that any given amount of reserves or monetary base will support less deposits, and hence less money supply. Conversely, if the Fed lowers the reserve requirement ratio, the deposit multiplier will increase, meaning that any given amount of reserves or monetary base will support more deposits and hence more money supply. Recall that the foregoing analysis requires that we assume that (i) the banks lend all of their excess reserves, and (ii) members of the nonbank public deposit all of the proceeds of loans in deposit accounts and do not hold any portion in currency, i.e., there is no currency drain from the banking system. If either of these assumptions does not hold, the multiple deposit expansion will be smaller than we have indicated, i.e., the multiplier will be smaller. In effect, the ten-fold increase in deposits, and therefore money supply, over and above the initial injection of monetary base, is a maximum, assuming no excess reserve holdings and no currency drain. Any excess reserve holdings or currency drain will lower the multiplier below ten.