The Income Statement

advertisement

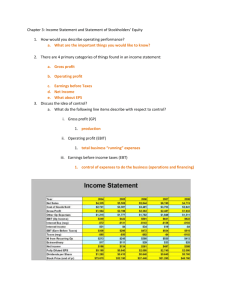

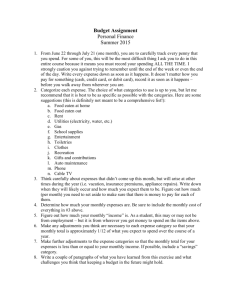

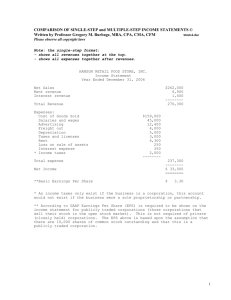

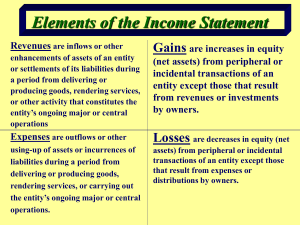

The Income Statement Chapter 4 Introduction • Four major types of items appear on income statements. – – – – Revenues Expenses Gains Losses Revenues • Revenues are inflows of assets (or reductions in liabilities) from providing goods and services to customers. • Revenues arise from the firm's ongoing, central operations. Expenses • Expenses arise from consuming resources in order to generate revenue. • As is true for revenues, expenses arise from the firm's ongoing, central operations. Gains • Gains increase assets or decrease liabilities. – A gain differs from a revenue in that gains arise from peripheral transactions of the business. Gains • Gains increase assets or decrease liabilities. – A paper company earns revenues by selling paper. Gains • Gains increase assets or decrease liabilities. – If it sells extra equipment from the employee lounge for more than the equipment's carrying value, then it will have a gain, not revenue. Losses • Losses decrease assets or increase liabilities. – A loss differs from an expense, however, in that losses arise from peripheral transactions of the business. Losses • Losses decrease assets or increase liabilities. – Returning to the above example—if the paper company sells that extra equipment for less than its carrying value, then it will have a loss, not an expense. The Materiality Principle • The materiality principle states that separate disclosure on a financial statement is not required if an item is so small that knowledge of it would not affect the decision of a reasonable financial statement reader. Net Sales • Net sales is the difference between gross sales and certain items, such as sales returns. Gross Margin • Gross margin is the difference between net sales and cost of goods sold. Selling Expenses • Selling expenses include any expenses necessary for the sale of goods, such as advertising and commissions. Administrative Expenses • Administrative expenses include expenses related to the administration of the business, such as management salaries and legal and accounting fees. Operating Income • Operating income is the difference between gross margin and selling and administrative expenses. Operating Income • When interest and income tax expense are deducted from operating income, the result is net income. Remember the following important difference: • Revenue refers to the total inflow of assets or reduction in liabilities. • Profit is the net increase in a firm's recorded wealth after deducting expenses. Presenting the Income Statement • Income statements may be presented in several different formats. – The multiple-step income statement shows various relationships. – The single-step format adds up all revenues and all expenses and does a single step, a subtraction, with the totals. Multi-Step Income Statement Net Sales Cost of sales Gross profit Selling, general and administrative expenses Income from operations Other income Interest expense Income before provision for income taxes Provision for income taxes Net income $ 172,428 134,373 38,055 14,844 23,211 1,503 31 24,683 10,016 $ 14,667 Single Step Income Statement Revenues Net sales $172,428 Other income 1,503 Expenses Cost of goods sold $134,373 Selling, general and administrative expenses 14,844 Interest expense 31 Provision for income taxes 10,016 Total expenses 159,264 Net income $ 14,667 Uses of the Income Statement • A major purpose of the income statement is to show a firm's profitability. • Investors, lenders, and company management all use income statement information for their assorted purposes. Revenue Recognition • A firm’s earning process often takes place over an extended period of time. Revenue Recognition Principle • One of the generally accepted accounting principles is the revenue recognition principle. Revenue Recognition Principle • The revenue recognition principle states that revenue should be recognized in the accounting records when the earnings process is substantially complete and the amount to be collected is reasonably determinable. Revenue Recognition Principle • In most cases, revenue is recognized at the point of sale. Revenue Recognition Principle • Revenue is earned, and thus recorded, whether or not cash is received. Revenue Recognition Principle • Payment for a good or service may be in the form of cash or an account receivable. Exceptions to the Revenue Recognition Principle • There are several exceptions to the revenue recognition principle. Exceptions to the Revenue Recognition Principle • If a seller is highly uncertain about the collectibility of receivables, then he should not recognize revenue until he receives cash. Exceptions to the Revenue Recognition Principle • With respect to long-term construction contracts, a contractor may use the percentage-of-completion method to record revenues and profits periodically. Exceptions to the Revenue Recognition Principle • Another exception is certain service contracts. Revenue Recognition • A company ought to disclose its revenue recognition policies in the notes to the financial statements. Expense Recognition • The matching principle drives expense recognition. Matching Principle • It states that costs incurred to generate revenue appearing on the income statement in a given period should appear on the income statement in that same period. Matching Principle • The matching principle is implemented in one of three ways. Matching Principle • First is associating cause and effect, which implies that there is a clear and direct relationship between an expense and a revenue. Matching Principle • Second is systematic and rational allocation, which is used when a cost cannot be directly linked to specific revenue transactions—the cost is simply allocated over time. Matching Principle • Third is immediate recognition, used when costs have no discernible future benefit and thus are expensed immediately. A Closer Look at the Income Statement • Income statements summarize past transactions and events. • But many financial statement users are concerned about the future, about earnings sustainability. A Closer Look at the Income Statement • GAAP requires that income statements report certain items separately from ongoing operations. – Examples include discontinued operations and extraordinary items. Discontinued Operations • Discontinued operations occur when a firm ceases, or plans to cease, operating, a major segment of its business. Discontinued Operations • There are two line items. – The results of operating the segment. – The loss realized on the disposal. – These items are shown net of income tax. Discontinued Operations • Since there is presumably a loss on discontinued operations, the tax effect is a tax benefit because losses lower the taxes a firm must pay. Discontinued Operations • To make predictions about future earnings, most analysts will add back the losses to reported net earnings to obtain adjusted net earnings because the discontinued operations results will not recur in the future. Extraordinary Items • Extraordinary items are events and transactions that are unusual in nature and infrequent in occurrence. – Evaluating both of those characteristics requires great judgment on the part of the accountant who decides whether or not an item is extraordinary. Extraordinary Items • These items, such as natural disasters and a foreign government's expropriation of a firm's assets, are also shown net of income tax. Extraordinary Items • An extraordinary item may be either a gain or a loss. Earnings Per Share • Earnings per share must be disclosed on the face of the income statement. Earnings Per Share • Earnings per share is computed by dividing net income by the average number of shares of stock outstanding. Net income EPS = Shares outstanding Earnings Per Share • Earnings per share is computed by dividing net income by the average number of shares of stock outstanding. – If net income is $100,000, and there are 200,000 shares of stock outstanding, then earnings per share is $ .50 ($100,000/200,000). Analyzing the Income Statement • The income statement contains a number of measures related to a firm’s ability to generate earnings. • This helps analysts assess a firm’s expected return. Vertical Analysis • Vertical analysis examines relationships within a given year. – This is accomplished by dividing each line of the income statement by the first item, which is net sales. – This yields common-size income statements in percentage terms. Common-Size Income Statements • The top line will always be 100% because net sales divided by itself yields 100%. Common-Size Income Statements • The second line—cost of products sold divided by net sales—is referred to as the cost of goods sold percentage. Common-Size Income Statements • The third line—gross profit (or gross margin) percentage—is calculated by dividing gross profit by net sales or by subtracting the cost of goods sold percentage from 100%. Common-Size Income Statements • The fourth line reflects the relationship between selling, general, and administrative expences. Common-Size Income Statements • The operating income percentage is a measure of management's success in operating the firm. Common-Size Income Statements • The net income percentage is a measure of the firm's overall profitability. Common-Size Income Statements • A lower cost of goods sold percentage and a higher gross profit percentage are desirable. Income Statements Year Ended December 31, 1997 1996 Net Sales Cost of products sold Gross profit Selling, general, & administrative expenses Special charges and plant closings Royalty income, net Operating income (loss) Interest expense Other income Income (loss) before taxes Income taxes (benefit) Net income $395,196 250,815 144,381 115,439 $444,766 300,495 144,271 122,055 32,900 (7,945) (6,100) 36,887 (4,584) (305) (1,088) 1,605 1,575 38,187 (4,097) 15,629 (5,216) $ 22,558 $ 1,119 Common-Size Income Statements Year Ended December 31, 1997 1996 Net Sales Cost of products sold Gross profit Selling, general, & administrative expenses Special charges and plant closings Royalty income, net Operating income (loss) Interest expense Other income Income (loss) before taxes Income taxes (benefit) Net income 100.0% 63.5 36.5 29.2 (2.0) 9.3 (0.1) 0.5 9.7 4.0 5.7% 100.0% 67.6 32.4 27.4 7.4 (1.4) (1.0) (0.2) 0.3 (0.9) (1.2) 0.3% Trend Analysis • Trend analysis involves comparing financial statement numbers over a period of time. • One way to accomplish this is to compare the common-size income statement items over a period of time. Horizontal Analysis • Another form of trend analysis is horizontal analysis. Horizontal Analysis • Horizontal analysis uses the figures from a prior year's income statement as the base year for calculating percentage increases over a period of time. Horizontal Analysis • Assume that net income for 1996 is $100,000 and for 1997 is $110,000. • Net income has thus increased by $10,000. – Dividing the $10,000 increase by the 1996 base year net income number of $100,000 shows that net income has increased by 10% from one year to the next. The Return on Shareholders' Equity Ratio • The return on shareholders' equity (ROE) ratio is computed by dividing net income by average shareholders' equity. Net income ROE = Average shareholders' equity The Return on Shareholders' Equity Ratio • Average shareholders' equity is computed by adding the beginning-ofthe-year and the end-of-the-year shareholders' equity balances and then dividing the total by 2. Return on Assets Ratio • The return on assets (ROA) ratio relates a firm's earnings to all assets the firm has available to generate those earnings. Return on Assets Ratio • It is computed by dividing average total assets into the sum of net income and interest expense (net of income tax). ROA = Net income + Interest expense (1 - tax rate) Average total assets Times Interest Earned • The times interest earned ratio shows how many times interest expense is covered by resources generated from operations and is very important to creditors of a business. Times Interest Earned • It is computed by dividing earnings before interest and taxes by interest expense. Times interest expense = Earnings before interest and taxes Interest expense Times Interest Earned • A creditor would certainly prefer a high number instead of a low number for this ratio. Limitations of Accounting Income • For some assets, an increase in value is recognized only at the disposal of the asset. • Financial statements often do not reflect accomplishments of a firm, as in the case of an executory contract. Limitations of Accounting Income • The conservatism principle, one of the generally accepted accounting principles, also may limit the extent to which accounting income reflects changes in wealth. Limitations of Accounting Income • The conservatism principle states that when given a choice between or among acceptable alternatives for treatment for a transaction, the accountant should choose the alternative which least overstates assets and income. Accounting Income and Economic Consequences • Reported earnings have an affect on managers' wealth and consequently, on their accounting policy decisions. – Bonuses can motivate a company's managers to make accounting-related decisions that do not affect the underlying profitability of the company but that do affect reported accounting income. Accounting Income and Economic Consequences • Reported earnings have an affect on managers' wealth and consequently, on their accounting policy decisions. – Because managers' self-interests influence their accounting policy judgments, financial statements may not be an unbiased reflection of the underlying economic activities of a firm. The Income Statement End of Chapter 4