Learning

advertisement

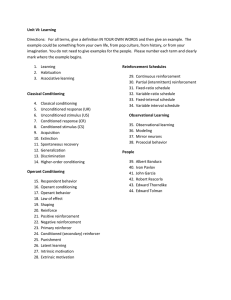

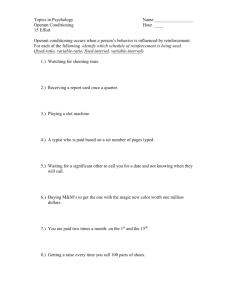

AP Psychology Learning aversive conditioning Aversive conditioning is the process of influencing behavior by means of unpleasant stimuli. There are two ways in which unpleasant events affect our behavior – as negative reinforcers and as punishers. If a child begins reaching for an electrical outlet, some parents let out a sharp “no” and follow it with a smack on the hand. Soon, the child begins to associate approaching an electrical outlet with a loud and mean-sounding rebuke from his/her parents and a smack. The child will then seek to avoid that in the future by avoiding the electrical outlets. behavior modification Behavior modification is a systematic usage of learning techniques designed to change behavior and/or feelings. Rehabilitation, as seen in prison, is often a form of behavior modification – an approach towards first desocialization (getting rid of the bad modes of behavior) and then resocialization (inserting better, socially-acceptable modes of behavior) so that a person can more easily integrate into society. biological preparedness Based on the work of John Garcia, biological preparedness involves a species-specific predisposition to be conditioned in certain ways and not others. Garcia attached it to food aversion. We seek to avoid the food that is bad for us as a survival instinct so natural selection favored those who avoided foods that make us sick. Martin Seligman extended the idea of preparedness to phobias. Some phobias come easily after unpleasant experiences (spiders, heights, darkness) while other such experiences do not cause phobias (knives, hot stoves and electrical outlets). The situations that cause quick development of phobias are likely a product of evolution and are ingrained. classical conditioning Classical conditioning is a learning process by which associations are made between a natural stimulus and a neutral or new stimulus. Ivan Pavlov’s landmark study with a dog showed that formally neutral stimuli can be conditioned to create a response that would not have been possible before conditioning – in this case, using a bell or chime to trigger salivation. classical conditioning: acquisition Acquisition refers to an initial stage of learning something. Ivan Pavlov theorized that acquisition to a CR depends on the stimuli occurring together in time and space. Yet more is required because you are constantly bombarded by stimuli that can be grouped together. Stimuli that is unique or unusual has a greater chance of being a CS. The timing of stimuli presentations also has an impact: CS-UCS occurring at the same time (simultaneous conditioning). CS begins right before the UCS and tops at the same time as the UCS (short-delayed conditioning). CS begins and ends before the UCS is presented (trace conditioning). Short-delayed conditioning tends to be more impactful and likely to lead to acquisition. classical conditioning: backward conditioning In backward conditioning, the unconditioned stimulus (UCS) is presented before the conditioned stimulus (CS). This does not prove to be as effectual as the typical pattern of classical conditioning. classical conditioning: conditioned stimulus (CS) and response (CR) A conditioned stimulus (CS) refers to a once-neutral event that elicits a given response after a period of training in which it has been paired with an unconditioned stimulus. A conditioned response (CR) is a learned reaction to a conditioned stimulus. An example would be a young child who has never seen a dog before so, upon seeing one, is curious. However, when the dog bites the child, the child will have learned fear of the dog and move away from one in the future. classical conditioning: conditioned taste aversion You are having dinner with some friends at a new restaurant and you order the fish of the day (one you’ve never tried) in a delicious lemon sauce with rice and broccoli. Six hours later, you become incredibly sick to the point that afterwards, the smell of fish and lemon sauce make you nauseous. There were a plethora of things that could have caused the same nausea but people often attribute such symptoms to the food. Conditioned taste aversion, established by John Garcia, is the tendency to combine the food (taste stimuli) and nausea, leading to an automatic assumption of cause and effect. Garcia attributed this tendency to part of an evolutionary process, helping us to avoid bad foods in order to prevent illness or even death. classical conditioning: delayed conditioning Delayed conditioning refers to the introduction of the conditioned stimulus and its continued engagement until the unconditioned stimulus is introduced. This is also referred to as forward conditioning. So, in Pavlov’s experiment, the bell continues to ring until the food is presented. classical conditioning: discrimination Discrimination is when an organism learns to differentiate between similar stimuli. Consider the Little Albert experiment (1920). John B. Watson and Rosalie Raynor conditioned the baby to fear all little white, furry items. If Albert could have restricted his fears only to the original stimuli or things directly associated with it, this would have been an example of discrimination. Your dog, over time, learns to distinguish between ordinary cars driving close to the house and your car driving up to the house, at which point, he begins barking happily and wagging his tail. This is a form of discrimination. classical conditioning: extinction Extinction is the process of wiping out conditioned responses by disassociating a particular conditioned stimulus and an unconditioned stimulus. It is important to know that conditioned behavior can never be totally wiped out and can be brought back under the right circumstances but typically not to the extent that it was before. classical conditioning: generalization Generalization is when an organism responds similarly to a range of similar stimuli. A person who is afraid of small dogs might also be afraid of animals of a similar size and shape. The aforementioned Little Albert grew scared of all small, white, furry things as a result of his conditioning with John B. Watson. classical conditioning: higher order conditioning Higher order conditioning is a sort of add on to the original conditioning. A second neutral stimuli is added to a conditioned stimuli to produce a conditioned response. The success of this effort would be seen by removing the original conditioned stimuli to see if the subject responds to the new stimuli. Both should create the same desired response. classical conditioning: neutral stimulus (NS) This is a great example I came across in a psychology website. You take your toddler to the doctor for an immunization shot. Once in the room, the doctor presses a button to ask for a nurse to help administer the shot. The toddler notices the buzzer sound but gives no importance to it. However, over time and after multiple visits, the toddler will grow conditioned to associated the previously insignificant buzzer (neutral stimulus) with the shot and the pain that ensues. classical conditioning: simultaneous conditioning Simultaneous conditioning is a form of conditioning when the conditioned stimuli and the unconditioned stimuli are presented together. classical conditioning: spontaneous recovery Spontaneous recovery refers to the reappearance of an extinguished response after a period of non-exposure to the conditioned stimulus. Extinction does not mean that something has been unlearned but rather the learned behavior has been suppressed. classical conditioning: trace conditioning Trace conditioning is when a subject is presented with a conditioned stimulus (it begins and ends) before the introduction of the unconditioned stimulus. classical conditioning: unconditioned stimulus (US) and response (UR) An unconditioned stimulus (UCS) is an event that elicits a certain predictable response without previous training. For example, a steak or your favorite food item placed in front of you is going to cause your mouth to salivate. The steak or favorite food item is the UCS. An unconditioned response (UCR) is an organism’s automatic (or natural) reaction to stimulus. In the above example, the salivating is the UCR. contiguity (Ivan Pavlov) Ivan Pavlov theorized that acquisition is to a conditioned response depends on stimulus contiguity – a stimuli that occurs together in time and space. Yet more is required because you are constantly bombarded by stimuli that can be grouped together. Stimuli that is unique or unusual has a greater chance of being a conditioned stimulus. contingency (Robert Rescorla) In the 1960s, an American psychologist named Robert Rescorla put forth an alternative to the classical conditioning first proposed by Ivan Pavlov. Rescorla suggested that while it was possible for learning to take place in the way in which classical and operant conditioning operates but it is not a guarantee. While Pavlov suggested a contiguity must exist between conditioned and unconditioned stimuli for learning to take place, Rescorla said it was more important that a contingency or correlation exist between the two. insight As a part of problem solving, insight is the sudden realization of the correct answer typically following a series of failed attempts. This is typically done as a product of trial and error. instinctive drift Learning theorists have generally believed that conditioning concepts can apply to a wide-range of organisms. Recently, scientists have determined there are biological-based limitations to how generalized conditioning principles can be. Instinctive drift is one of the biological constraints on learning, occurs when an animal’s innate response tendencies interfere with conditioning processes. Keller and Marian Breland discovered that some genetic instincts would often interrupt attempts at conditioning. Teaching raccoons to place a coin in a box worked until more than one coin was used – the raccoons began to associate the coins as food itself and began “washing” them instead of giving them away. instrumental learning law of effect Instrumental learning is another name for operant conditioning, coined by Edward Thorndike to emphasize this responding as instrumental to reaching a desired outcome. He placed a hungry cat in a box with food just outside of it, providing obstacles for the cat to navigate to get the food. Over time, the cat gradually got out of the box quicker and to the food faster. Thorndike called this the law of effect – if a response in the presence of a stimulus leads to satisfying effects, the association between the stimulus and the response is strengthened. This idea was the cornerstone of Skinner’s work though using different terminology. latent learning Latent learning, an example of cognitive learning, is learning that does not create an immediate or observable change in behavior. Typically, it does not make itself apparent until a reinforcer emerges. A person who has ridden with someone to Dallas might not know the way to get to Dallas (and why would you want to) but there are various landmarks and significant features that the person would recognize – things they remember with no intention of doing so. It will not emerge until later when they are tasked with driving to Dallas on their own and begin piecing things together. learning Learning refers to a relatively durable change in behavior or knowledge that is due to experience. In everything we do, in every way we act and react, we are displaying the product of learning. From a psychological point of view, this focus is on a particularly type of learning called conditioning which is learning associations between events that occur in an organism’s environment. observational learning Observational learning occurs when an organism’s response is influenced by its observation of others, called models. Albert Bandura suggested that classical and operant conditioning can happen through observation – one learns by watching another’s conditioning. Bandura identified four key processes needed in observation learning: Attention – one can hardly learn without paying attention. Retention – an ability to remember what may take days, weeks or months to have the chance to do themselves. Reproduction – one’s ability to reproduce what has been seen though reproducing is not a given. Motivation – one must also be motivated to duplicate what is observed. operant conditioning Operant conditioning is learning is when a certain action is reinforced or punished for the purposes of increasing or decreasing the behavior. Pioneered by B.F. Skinner, it is an attempt to regulate voluntary responses to stimuli. operant conditioning: chaining Chaining is learned reactions that follow one another in sequence, each reaction producing the signal for the next. For example, swimming is a skill that involves three major acts or chains that combine to make up the whole swimming pattern – an arm stroke chain, a breathing chain and a leg-kicking chain. Once learned, the individual parts are no longer distinguishable but happen fluidly, as it were, in one motion. operant conditioning: escape and avoidance conditioning Two uses of negative reinforcement that have been studied in detail are escape conditioning and avoidance conditioning. Escape conditioning refers to the training of an organism to remove or terminate an unpleasant stimulus. A child who is given liver for dinner might balk by whining or gagging. If the liver is removed, the whining and gagging have become negatively reinforced. Avoidance conditioning is the training of an organism to withdraw from or prevent an unpleasant stimulus before it starts. In the above example, the child whining and gagging as the father takes the liver from the refrigerator would be an example of avoidance. operant conditioning: generalized reinforcer You are walking down the street one day and you see a guy coming out of a very nice and expensive red sports car and walking to meet a beautiful woman dress for a fancy event while the man is dressed similarly in clothes from a very expensive haberdashery. The fancy clothes, the beautiful partner and the expensive and fast sports car are all symbols or generalized reinforcers to the importance we place on wealth, power, fame strength and intelligence. Most such reinforcers are culturally based and reinforced. operant conditioning: negative reinforcement Negative reinforcement is increasing the strength of a given response by removing or preventing a painful stimulus when the response occurs. If walking with a stone in your shoe causes you to limp, removing the stone (negating it) allows you to walk without pain. More common negative reinforcers are fear and social disapproval. operant conditioning: omission training Omission training is utilized to get rid of undesirable behaviors, by taking something the subject enjoys as punishment for certain types of behavior. Parents will often ground a child in their room in response to some action they committed. In doing so, television, computers and other favorite items are removed so that the child, ideally, has time to consider what they have done and ensure they don’t do it again. It is a form of leverage against the child to convince the right path to take. operant conditioning: positive reinforcement/reinforcer Originally put forth by B.F. Skinner, positive reinforcement is seen when a response is strengthened because it is followed by the presentation of a rewarding stimulus. Examples of positive reinforcers include money, praise and food/candy. These examples are also known as secondary reinforcers. operant conditioning: Premack principle As put forth by David Premack (1965), the Premack principle is an element of operant conditioning that says reliable behavior can be used as a reinforcer to behavior not as reliable. Your mother comes into your room and says that the lawn needs to be mowed (less reliable behavior). Of course, as a teenager with less than optimal motivation, you moaned. Your mother counters by saying that a well-mowed lawn means a visit to your favorite restaurant (very reliable behavior). Sparked by motivation, you do the best mowing the neighborhood has ever seen. Not the best way to get something done but it certainly is used. operant conditioning: primary and secondary reinforcer Primary reinforcer is a stimulus that is naturally rewarding, such as food or water. Secondary reinforcer is a stimulus such as money that becomes rewarding through its link with a primary reinforcer. operant conditioning: punishment As put forth by B.F. Skinner, punishment is seen when an event following a response weakens the tendency to make that response. This can be done with negative stimuli or the removal of a positive stimuli – one can be spanked (negative) or have privileges taken away (removal of the positive). Punishment is not the same thing as negative reinforcement. Negative reinforcement removes an adverse stimuli (strengthening response) while punishment presents the same (weakening response). Punishment is not just what parents or authority figures do – kids teasing a fellow kid for wearing shoes that are no longer in style. Punishment as discipline can create side-effects including wiping out more than the undesirable behavior, creating strong emotional responses and increasing aggressiveness. operant conditioning: shaping Shaping is a technique in which the desired behavior is “molded” by first rewarding any act similar to that behavior and then requiring ever-closer approximations to the desired behavior before giving the reward. reinforcement schedule: continuous reinforcement Continuous reinforcement occurs when every instance of a designated response is reinforced. However, studies show that such reinforcement does not create behavior very resistant to extinction. For example, recent studies have shown that excessive praising with elementary students ultimately erodes a child’s willingness to try and elicit such a reinforcement. Even small children understand that excessive praise is insincere. For high school students, the omnipresent grades have proven just an unreliable as a form of reinforcement. reinforcement schedule: fixed ratio and interval A fixed-ratio schedule is a pattern of reinforcement in which a specific number of correct responses is required before reinforcement can be obtained. An example of this can be a person who is paid for each page of information that is typed onto a word document. The more that is typed, the more that is paid out. A fixed-interval schedule is a pattern of reinforcement in which a specific amount of time must elapse before a response will elicit reinforcement. The fact that quizzes and tests will spur on activity, that activity will almost immediately drop off afterwards. These assessments are given at a fixed-interval schedule. reinforcement schedule: partial reinforcement Also known as intermittent reinforcement, partial reinforcement occurs when a designated response is reinforced only some of the time. According to studies, it appears that partial reinforcement makes response more resistant to extinction than other forms such as continuous reinforcement. reinforcement schedule: variable ratio and interval A variable-ratio schedule is a pattern of reinforcement in which an unpredictable number of responses are required before reinforcement can be obtained. An example of this can be a telemarketer who does not know how many phone calls they will have to make before being successful. A variable-interval schedule is a pattern of reinforcement in which changing amounts of time must elapse before a response will obtain reinforcement. Constantly trying to call a friend when the line is busy will ultimately produce a reinforcer as soon as the friend has hung up. superstitious behavior Superstitious behavior is the product of a reinforcer or punisher occurring shortly after an unrelated behavior. For example, you are walking down the street and a black cat runs in front of your path. Seconds later, you trip and fall flat on your face. The fall (reinforcer) is connected to the cat (unrelated behavior) to condition you to believe there is a connection (black cats are bad luck).