amendment xv

advertisement

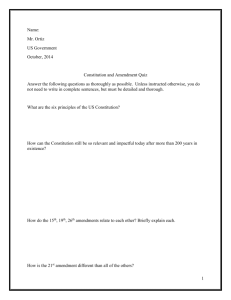

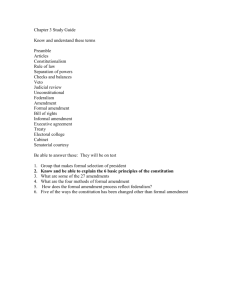

P5 | APUSH | Ms. Wiley | Civil War Amendments, D___ Name: Summary Excerpts from PBS and the Constitutional Rights Foundation Overview: In the wake of the Civil War, three amendments were added to the U.S. Constitution. The Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery (1865), the Fourteenth Amendment made freed slaves citizens of the United States and the state wherein they lived (1868), and the Fifteenth Amendment gave the vote to men of any race (1870). During this time, the nation struggled with what role four million newly freed slaves would assume in American life. With the triumph of the Radical Republicans in Congress, the Constitution was amended to grant full citizenship to former slaves and promise them equal treatment under the law, a promise that took more than a century to fulfill. The three amendments added to the Constitution after the Civil War—the 13th, 14th, and 15th but especially the 14th—have been the most important additions to the Constitution since the original Bill of Rights. They—and especially the 14th—have also been among the most puzzling features of the Constitution. Seeing them in the light of their connection to natural rights helps to make sense of the amendments. 13th and 14th Amendments: The three amendments were not adopted all at once, but in succession. The 13th Amendment was adopted in the immediate wake of the Civil War and had the simple and relatively straightforward task of forbidding slavery anywhere in the United States. The original Constitution contained no constraints on the power of the states to institute (or not to institute) slavery and the amendment took that power away from the states. It was an attempt to give constitutional embodiment to a central “natural right”—the right to liberty. The Congressional Republicans who pushed the amendment through did not conceive of it as the first in a series, but expected it to suffice. However, there were several severe legislative challenges from the defeated former slave states that required the Republicans to revisit the issue. A series of laws called Black Codes was passed in most of the former confederate states, which laws did not in so many words return the freedmen to the state of slavery, but did clearly discriminate against and disadvantage them. The 13th Amendment contained a clause empowering Congress to enforce its provisions by appropriate legislation, and a debate arose in Congress over whether legislation overturning the Black Codes was appropriate legislation under the Amendment. The result of the debate was the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and the adoption by Congress of a new draft amendment—the 14th Amendment. The amendment was thought to be desirable for two reasons: first, there were those who had their doubts about the constitutional legitimacy of the Civil Rights Act under the 13th Amendment. But, second, many thought it desirable to build directly into the Constitution express protection against laws like the Black Codes. The relevant parts of the 14th Amendment had five main clauses: (1) a clause defining who are citizens; (2) a clause providing protection against state abridgements of “the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States”; (3) a clause forbidding the states to deny to any person life, liberty, or property without due process of law; (4) a clause imposing a duty on states not to deny “equal protection of the laws” to any person within their jurisdictions; and (5) a provision granting Congress the power to enforce the amendment. A key feature of the Fourteenth Amendment was that it directly prohibited certain actions by the states. It also gave Congress the power to enforce the amendment through legislation. The Fourteenth Amendment represented a great expansion of the power of the national government over the states. It has been cited in more Supreme Court cases than any other part of the Constitution. In fact, it made possible a new Constitution—one that protected rights throughout the nation and upheld equality as a constitutional value. Note that the Fourteenth Amendment introduced the ideal of equality to the Constitution for the first time, promising “equal protection of the laws.” [The principle of equality, “all men are created equal,” is found in the Declaration of Independence, not the Constitution.] 1 With the exception of Tennessee, the Southern states refused to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment. The Republicans then passed the Reconstruction Act of 1867, which set the conditions the Southern states had to accept before they could be readmitted to the union, including ratification of the 14th Amendment. The 15th Amendment: At the time of Ulysses S. Grant's election to the presidency in 1868, Americans were struggling to reconstruct a nation torn apart by war. Voting rights for freed blacks proved a big problem. Reconstruction Acts passed after the war called for black suffrage in the Southern states, but many felt the approach unfair. The Acts did not apply to the North. And in 1868, 11 of the 21 Northern states did not allow blacks to vote in elections. Most of the border states, where one-sixth of the nation's black population resided, also refused to allow blacks to vote. In the North, the Republican’s once-huge voter majority over the Democratic Party was declining. Radical Republican leaders feared that they might lose control of Congress to the Democrats. One solution to this problem called for including the black man’s vote in all Northern states. Republicans assumed the new black voters would vote Republican just as their brothers were doing in the South. By increasing its voters in the North and South, the Republican Party could then maintain its stronghold in Congress. The Republicans, however, faced an incredible dilemma. The idea of blacks voting was not popular in the North. In fact, several Northern states had recently voted against black male suffrage. Republicans' answer to the problem of the black vote was to add a Constitutional amendment that guaranteed black suffrage in all states, and no matter which party controlled the government. The writers of the Fifteenth Amendment produced three different versions of the document. The first of these prohibited states from denying citizens the vote because of their race, color, or the previous experience of being a slave. The second version prevented states from denying the vote to anyone based on literacy, property, or the circumstances of their birth. The third version stated plainly and directly that all male citizens who were 21 or older had the right to vote. Determined to pass the amendment, Congress ultimately accepted the first and most moderate of the versions as the one presented for a vote. This took some wrangling in the halls of Congress, however. The Democrats realized they were fighting for political survival. They feared ratification of the 15th Amendment would automatically create some 170,000 loyal black Republican voters in the North and West. In debates over the amendment, Democrats argued against the ratification by claiming that the 15th Amendment restricted the states’ rights to run their own elections. The Democrats also charged the Republicans with breaking their promise of allowing the states, outside the South, to decide for themselves whether to grant black male suffrage. Democrat leaders cited the low level of literacy in the black population and they predicted black voters would be easily swayed by false promises and outright bribery. Congress passed the Fifteenth Amendment on February 26, 1869. But some states resisted ratification. At one point, the ratification count stood at 17 Republican states approving the amendment and four Democratic states rejecting it. Congress still needed 11 more states to ratify the amendment before it could become law. All eyes turned toward those Southern states which had yet to be readmitted to the Union. Acting quickly, Congress ruled that in order to be let into the Union, these states had to accept both the Fifteenth Amendment and the Fourteenth Amendment, which granted citizenship to all people born in the United States, including former slaves. Left with no choice, the states ratified the amendments and were restored to statehood. Finally, on March 30, 1870, the Fifteenth Amendment became part of the Constitution. To many, it felt like the last step of reconstruction. But just as some had predicted, Southerners found ways to prevent blacks from voting. Southern politics would turn violent as Democrats and Republicans clashed over the right of former slaves to enter civic life. White supremacist vigilante groups like the Ku Klux Klan gained strength as many whites refused to accept blacks as their equals. Within a few years, the Southern state governments required blacks to pay voting taxes, pass literacy tests and endure many other unfair restrictions on their right to vote. In Mississippi, 67 percent of the black adult men were registered to vote in 1867; by 1892 only 4 percent were registered. Another 75 years passed before black voting rights were again enforced in the South. 2 AMENDMENT XIII (passed January 31, 1865; ratified December 6, 1865) Section 1. Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction. Section 2. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation. AMENDMENT XIV (Excerpt) (passed June 13, 1866; ratified July 9, 1868) Section 1. All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are Citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws. Section 5. The Congress shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article. AMENDMENT XV (passed February 26, 1869; ratified February 3, 1870) Section 1. The right of Citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude. Section 2. The Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation. 3 4