a study in the book of philemon-3 june 28, 2015

advertisement

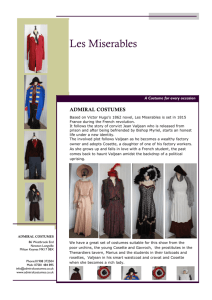

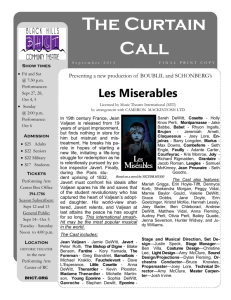

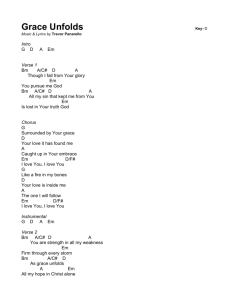

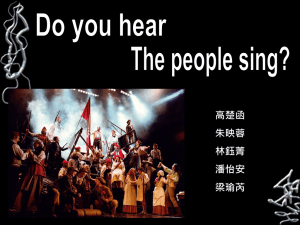

A STUDY IN THE BOOK OF PHILEMON-3 JUNE 28, 2015 Hopefully some of you have been inspired by this sermon series over the last couple of weeks. Some of you have been inspired by the sermons, but I know many of you have been inspired by the music. So inspired that you might want to put on a presentation of Les Miserables. I’ve got good news and bad news, you can do it, but it will cost you something in more ways than one. Les Miserables first was presented in its current form in London in 1985. It then began showing on Broadway in 1987 where it would continue to show regularly until 2003. It has sprung up in various revivals in major cities, but overall it has been very tightly controlled. Some musicals are recast, reimagined and completely changed and reworked into new forms, but not Les Miserables. Aside from one recent version, the musical of Les Miserables is not allowed to be altered or changed. If you want to show it, you have to enter into a licensing agreement, and that means your version of Les Miserables needs to look like the original. Which means you need a lot of talented people, a lot of costumes and a lot of sets. This strict licensing exists for many reasons, of course. One major reason is money. The Broadway version alone has made close to half a billion dollars. Money aside, you can also see why they have these restrictions. They don’t want Les Miserables watered down. When someone mentions Les Miserables, they want the experience of two strangers to be mindblowingly the same. They don’t want one person thinking of the epic Broadway version while another person saw a version where Les Miserables was reimagined as the story of break-dancers from NYC who are struggling against Mayor Rudy Giuliani. Speaking of all of this licensing business, I’m not sure we are allowed to be singing and doing this at SFC. Normally, I encourage you to tell your friends about your church experiences but maybe not so with this. It will be our little secret. At the end of the day, for the creators of Les Miserables, it is quite important that Les Miserables always looks like Les Miserables. Continuity and consistency are important. I think this is something Jesus believed in as well. Jesus discussed a lot of topics, but they can all be connected under the heading of discipleship. A disciple is simply someone who patterns themselves after another. A disciple of Jesus tries to live and love like Jesus. When we learn about Jesus, as you well know, it is not interesting data we are collecting to put into our religion folders. When we learn about Jesus, we are trying to be more like him. That’s why Jesus’ teaching on forgiveness is so difficult. One of Jesus’ most striking passages on forgiveness is from Matthew 18. He tells the parable of a man who has lost a great fortune for his master. After pleading for leniency, the master completely forgives the debt. That same forgiven man then goes out and finds a man who owes him money. In the same way, the man asks for leniency for the paltry sum. The forgiven man refuses to forgive the debt. The master finds out about this travesty and throws the unforgiving forgiven man in jail. Jesus then ends with these words. Matthew 18:35 That’s quite a statement. It is just as strong in Matthew 6:15, if you do not forgive peoples’ sins against you, your Father will not forgive you. These are difficult sayings. On the cross, Jesus said, “tetelestai-it is finished.” We often discussed this as the finished work of Christ. We also read that Jesus says those who are his cannot be lost out of his hand. This sounds like your forgiven nature could be in the balance each new day. This sounds like if you die on the wrong day without having forgiven someone then God will not forgive you and your eternal destiny will be altered. What do you do with a passage like this? In one sense, Jesus wants disciples to be disciples. He wants continuity and consistency, but he also knows we are fragile and prone to regular sin. So what do you do with a passage like this? If you are new here with us or haven’t been here in awhile, we are concluding a short series on forgiveness from the book of Philemon. We say a book but it is really a letter, a short 25verse letter at that. It is a personal and yet public correspondence between Paul and a friend of his named Philemon. Philemon has a slave named Onesimus who has run away. Because a large portion of Romans were slaves, it was important to keep slaves in their place. So when a slave ran away, they could be beaten, tortured or even killed to send a message to the rest of the slaves. This runaway slave had become a Christian, and he is now asking Paul for help in this situation. He asks Paul to mediate and speak on his behalf. Each week, we have taken a look at the different roles in this story. Week one we looked at Philemon. We talked about the difficult task of offering forgiveness to those who offended you. To not only offer forgiveness, but “candlestick forgiveness” as seen in Les Miserables when the bishop rewards the wayward, violent Jean Valjean not only with his freedom but the parting gift of the expensive candlesticks. That moment of reckless and gratuitous grace changed Jean Valjean. Last week we looked at the role of Paul as a mediator or peacekeeper. Paul inserts himself in this precarious situation with a singular mindset to bring Onesimus home. It might be costly and complicated, but his mindset is that of Jean Valjean when it comes to Marius. Bring him home, no matter what. This last week, we will look at the person of Onesimus, the one needing forgiveness. What I really want to focus on this week is recognizing what a forgiven person looks like. To reacquaint ourselves with the depth of forgiveness offered to us and how that should change us. One way of reading those words from Jesus sounds like God is angrily waiting to rip forgiveness away from you. If you choose not to forgive, then God will angrily take away your salvation, and like the parable, toss you into punishing confinement. That further reinforces our worst view of God as an angry overlord who acts more like Javert than Valjean. I don’t think that is what those passages mean. I do think they carry a potent message though. As the choir sang for us in this final week’s medley, we heard the last confession of Jean Valjean. At the end of his life, he is passing off Cosette to the care of Marius, and he is revisiting his life. He says he was a man who turned from hating to one who only learned to love when Cossette was in his keeping. We see Valjean die and pass through to the final song. The final scene is a heaven-like place, the garden of the Lord. Using the words from Isaiah, they will no longer have war - their weapons will be turned into plowshares, and when they arrive at a place beyond the barricade, they find a world they longed to see. In the middle of all of this, is one of the most profound and talked about lines in the musical. Maybe even a thesis statement for this entire story. In this heavenly scene, Fontine, the bishop and Jean Valjean harmonize and sing, “And remember the words that once were spoken, to love another person is to see the face of God.” This could sound like an utterly humanist and secular phrase. There really is no God, but the closest we get to a divine experience in this life is loving another person. There is no way that’s what it means. It is a heaven-like experience filled with Biblical imagery talking about a future world of peace. This idea of “loving another person” as seeing the face of God has the same meaning as Jesus’ words from Matthew 18 and Matthew 6. It is speaking of the vicarious and interconnected divine/human relationship. It is speaking of the nature of forgiven people. This is an idea that is worth a more in-depth exploration. There is something mystical about the interconnectedness and vicariousness of God and people. While we have a vertical relationship with God, it is manifested almost entirely horizontally. Because God cannot be touched, smelled, seen or heard, it only makes sense that our primary experience of God is through one another. That might sound blasphemous, but it is not. Think about it God is spirit. We can anthropomorphize him all we want, but he is not a grandfatherly figure in the sky with white robes and a white beard. God is Spirit. So the primary way we experience God, receive love from him and show love to him is through other people. Aside from those who got a face-to-face with Jesus around 2,000 years ago, this is how our spiritual economy works. When you love others, you are loving God. When others are loving you, you are being loved by God. This is the vicarious economy of love. There are plenty of biblical examples of this vicarious experience of God. In Matthew 25, Jesus says, “When we serve the least among us, we are serving him.” John, the disciple, does the most work in fleshing out this point. John 13-17 is almost exclusively about Jesus illustrating the vicarious economy of love. In John 13, Jesus says when you love other people, people will know you know him. Repeatedly in John 14-15, Jesus says people will know you love me if you keep my commands, and then he says, “My command is this. Love one another.” Read it in your small group. He is repetitive. He says it and then says it again five verses later. You love me if you keep my command, and my command is to love one another: John 13:35 John 15:12 John 15:17 John 16:27 John 17:20-26 There are too many to count in 1 John. To love other people is to love God, the vicarious economy of love. The primary way our vertical relationship with God is played out is in how our horizontal relationships play out. This means your faith in God cannot be separated from causes regarding justice or human rights or starvation or slavery or oppression, and it cannot be separated from forgiveness. To love another person is to see the face of God. If you cannot forgive, then you cannot see God. Your vision is blocked, and it is cloudy. When Jesus says that you will not be forgiven if you choose not to forgive, he’s saying you never really experienced forgiveness. He’s not saying you had it and then it was taken away. He’s saying you never had it. You had a cheap knock-off, because if you have seen God, you can’t not love, you can’t not forgive. There is a version of Les Miserables out there that has taken the title of the show quite literally. You’ll remember Les Miserables means the miserable ones. This show is full of miserable ones, and you too will be miserable if you see it. I will not say where, but one high school was a little too audacious for their own good. I won’t show you a video because I don’t want to mock these students, but everything about it is bad. Shockingly so. Imagine if someone had never seen Les Miserables and that was their only experience, shoddy costumes, flat music and comically bad singing. Imagine someone who saw that saying, “I don’t really like Les Miserables.” You would understand why. Sometimes you have to do quality assurance. Jesus is saying, “If you have seen the real thing it will change you. You can’t not hum the tunes…you can’t not sing his praises. When you recognize that you are a slave set free, a dead man brought back to life, it changes you. You can’t not love. You can’t not forgive. The problem, of course, is grace entitlement. It’s receiving like Valjean but living like Javert. I told you in week one that the true miserable one in this story is Javert, the man of the law who is obsessed with meting out justice. When you first meet Javert, as he oversees the lawbreakers, he refers to Valjean as only a number 24601. Not a person to be loved, but a project to managed. When Valjean laments that he stole some bread for his starving sister, Javert says, “You will starve again unless you learn the meaning of the law.” He is harsh. He is a law-keeper. He is strict. There are plenty of Javerts in the Bible. Oblivious to the favor they have received and believe they are entitled to the grace they have received. The Javerts of the Bible are obsessed with grace for them and justice for you. They rarely love others because they don’t realized how much they have been loved. The most obvious Javert of the New Testament is the older brother in the prodigal son story. He has kept the law while his Jean Valjean of a brother has broken and re-broken the law. This particular Javert looked on in horror as his younger brother was welcomed back home. His father threw a party, and he threw a fit. The grace short-circuited his brain. The best Old Testament Javert is Jonah. It could easily be the tale of Javert and the Whale. Jonah Javert is sent to Nineveh to preach grace. He is not excited about this because Nineveh was a raucously pagan nation that lived how they wanted and was also a sworn enemy of Israel. They had killed Israelites and laughed at their God. Some have likened God’s request for Jonah to preach grace to pagan Nineveh to a Jew in the 1930’s to march through Berlin preaching grace. So Jonah Javert ran. He had forgotten the grace he had received and was reluctant to pass it along to others. The problem in both of these instances is grace entitlement. Over time we forget what it means to be a slave set free. We forget what it means to be a dead man brought back to life. The older brother Javert forgot that he was born into his Father’s rich household. He played no part in that birth. It just happened to him, and he was upset when his father allowed the younger brother to be reborn. Jonah Javert forgot that he was born into the chosen people. He played no part in that birth, it just happened to him, yet he was upset when his father allowed the Ninevites to be reborn. For all of us today, we are slaves set free. Modeling on the words of Jesus to Nicodemus, some Christians refer to themselves as “born again.” The great analogy about being born is that you do not choose to be born. It is something that happens to you. The same is true for being born again. God chooses you and allows your rebirth. Even responding to grace is a gift, yet when we attend church for a few decades and serve for a few decades and tithe for a few decades and participate in sanctification for a few decades, grace drift happens. We begin to think being born again has something to do with us. We might secretly think we earned a little merit. Unforgiving people have not truly known forgiveness. In his letter to Philemon, Paul says this: Philemon 19-20 Paul is calling to mind Philemon’s manumission. Philemon was once a slave to sin and death, but because of the work of Jesus Christ that Paul shared with him, he is a slave set free. Not too subtly, Paul is reminding Philemon that he is a slave who was set free. The vicarious economy of love is the great equalizer. If we are unwilling to love through forgiveness, then we might need a refresher on the grace we have received. A lot of Christians think like Valjean but live like Javert. A lot of Christians think like the prodigal son but live like the older brother. A lot of Christians think like the Ninevites but live like Jonah. To love another person is to see the face of God. Have you seen him? This is not a litmus test. If you are unforgiving, I am not challenging your faith or whether you are a true Christian. However, if you are unforgiving, I am simply asking you to look again. The vicarious economy of love is calling to you because when you refuse to forgive, you are refusing to love God. You are refusing to embrace grace and see the divine spark in your broken neighbors and family members. To love another person is to see the face of God. This is not simply a proclamation but an invitation. I will continue to say this to you in multiple sermons. God’s directives and commandments are for your joy. The call to forgiveness is the invitation to see God face-toface again. To be reacquainted with your brokenness. To be reminded of his generosity. To be reminded you are a slave set free who is to become obsessed with introducing others to the sweet taste of freedom. The great irony of the strict licensing of the musical Les Miserables is that the musical is not original material. Yes, the songs and music are original, but they are drawn from the original source material. Victor Hugo created the masterpiece of Les Miserables. It is impressive how the writer and song makers created the musical, but they simply were offering melody to a work already created. They were able to do this because modern copyright laws protect an artist’s work for 70 years after their deaths, but at that moment, the work then enters the public domain. From that moment on, anyone can re-purpose or re-use the work of Victor Hugo. Once it is in the public domain, it is a free gift. In a strange bit of irony, the creators of the Les Miserables musical are acting a bit like Javert. Stringently protecting a thing they didn’t originally create. After the death of Jesus, grace entered the public domain. A free gift for whoever wanted to pick it up and include it in their lives. God help us if we license it. God help us if we engage it for our use and prevent others from using it. Modern evangelicals can often be more Javert than Valjean, and that is not okay. More Jonah than Ninevite. More older brother than prodigal son. We are slaves set free. We are dead men brought back to life. The vicarious economy of grace is inviting you this week to forgive. It is inviting you to extend grace because forgiven people forgive people. My prayer for you this week is that you love another person and you see the face of God.