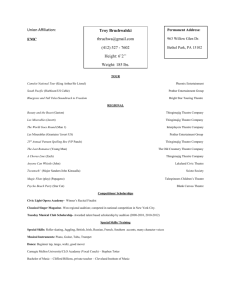

Sunday, 27th January, 2013 - The Very

advertisement

St Paul’s Cathedral A Sermon by The Very Reverend Dr Trevor James Dean of St Paul’s Cathedral Preached at the Eucharist on the Conversion of St Paul 27 January 2013 Texts: Acts 9:1-22; Matthew 19:27-30 This year our Feast of the Conversion of St Paul coincides with what might be described as the Summer of Les Miserables. I saw the film last week – and enjoyed it immensely. As we talked about it afterwards, Christine rightly observed that it was a deeply religious film. On the occasion of the Conversion of St Paul, one character in the musical comes immediately to mind, the policeman - Javert. As you will recall, Javert’s way of understanding himself and the world is that there is an absolute order, it is a moral order from which there may be no deviation and which, for any lapse, offers no forgiveness or mercy: it is an absolute and Javert clings to this certainty with all his being. The great song known as ‘Stars’ expresses his code – the stars order the cosmos, and their patterns and movements speak of this cold and indifferent moral order: He says… And so it is written On the doorway to paradise That those who falter and those who fall Must pay the price! His whole hope in life is that he has never faltered in his inflexible obedience to this code. He says But mine is the way of the Lord And those who follow the path of the righteous Shall have their reward This code psychically anchors him amidst the chaos and darkness of the world he inhabits, Paris in the year of the Commune. But of course the great theme that runs through Hugo’s novel is of something else – of forgiveness and selfless love. So when Javert finally and inescapably encounters this love and forgiveness, and cannot evade or deny it any longer, his world falls apart. The realisation simply destroys him. He has what we might call a psychotic break – and he throws himself into the Seine. He gave me my life, he gave me freedom. I should have perished by his hand! It was his right. It was my right to die as well Instead I live, but live in hell! And my thoughts fly apart Can this man be believed? Shall his sins be forgiven? Shall his crimes be reprieved? And must I now begin to doubt Who never doubted all these years? Now I have spent this time talking about Les Miserables and Javert because the dilemma of Javert could so easily have been the dilemma of the man who was first known as Saul of Tarsus. Long after his experience on the Damascus Road Paul boasted of his credentials as a Jew … If anyone else has reason to be confident in the flesh, I have more: circumcised on the eighth day, a member of the people of Israel, of the tribe of Benjamin, a Hebrew born of Hebrews; as to the law, a Pharisee; as to zeal, a persecutor of the church; as to righteousness under the law, blameless. (Philippians 3:5) Paul’s background, his whole mental world and his understanding of himself was anchored in that strongly centred and robustly framed world of strict Judaism. This culture and creed absolutely formed him – to be outside it was unimaginable; to conceive that it could be altered or amended in any way – unthinkable. Intellectually and emotionally it would appear that Paul was so formed that any departure from this way of being would have been utterly traumatising and alienating. If we think about the character of the man who appears in his letters we sense an utterly driven 2 and focused personality; a man totally committed. For someone like this a complete turnabout could have mentally and spiritually destroyed him. So, what happened to Saul the zealous Jew on the road? Certainly something very odd and that seems to evade all explanations. In Acts, despite Luke’s smooth and polished account of the mysterious event on the Damascus road, one senses that the actual events were complex and more chaotic and inexplicable than the narrative suggests. If we look at what is presented (rather than how it is framed) the recorded facts seem to hint at something like a dramatic and sudden psychic disintegration: Paul falls, he is incapacitated, blinded, and has to be led and cared for. While those with him heard something they saw nothing. What has Paul experienced? It is hard to imagine but it seems that he has come up against something that is so utterly different from everything he has previously believed or experienced that it is unnerving; mentally shattering; alien (not of the world as we know it); it annihilates everything about which he has ordered his life – and it is not surprising that he crashes – and experiences what might have been a psychotic break. What other alternatives are there to such an experience? Hugo has Javert commit suicide; Shakespeare has Lear descend into madness. In short, I suggest to you that Paul’s conversion was an immensely traumatic event. He encountered something not of this world – and there is no language or conceptual structure for that absolute otherness - and in the horror and awe of that mind-bending experience it was as if he died. A new and very different man was to appear – after 3 days. Can we face the questions Paul’s conversion puts to us? That it was no easy thing and that at its core is this terrifying encounter with the Holy – something so other, so different? This tests our vocabulary of faith; it bursts the naïve and simple constructions that we call ‘God’; it takes us beyond our comfort zones and into the unknown space and utter strangeness of the empty tomb. © Trevor James 2013 3