Role of Digital Storytelling in Interdisciplinary Collaborative

advertisement

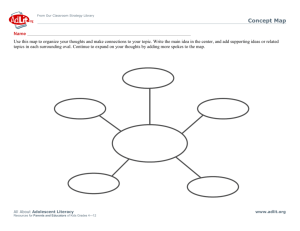

Role of Digital Storytelling in Interdisciplinary Collaborative Teaching Melda N. YILDIZ Kean University, United States myildiz@kean.edu Abstract: This presentation outlines the role of innovative interdisciplinary collaborations among the Asian Studies faculty in various disciplines; offers creative strategies and possibilities for integrating new technologies and 21st century skills into undergraduate curriculum; demonstrate Project Based Learning and experiential classroom activities; and showcases undergraduate students’ interdisciplinary multimedia projects and digital stories. We will explore wide range of meanings participants (undergraduate students) associated with experiential and exploratory learning activities; impact of new technologies in the curriculum; the ways in which participants integrated interdisciplinary topics into their multimedia projects; and how they gained alternative points of view on Asia and renewed interest and commitment to global stories and issues. Introduction Educators at all levels can use Digital Storytelling in many ways, from introducing new material to helping students learn to conduct research, synthesize large amounts of content and gain expertise in the use of digital communication and authoring tools. This study follows the process of digital storytelling among undergraduate students who were taking introduction to Asian Studies course and explores three key topics in order to understand the educational experiences of the participants: the wide range of meanings participants associate with multimedia production and media education; the impact of media production activities in the curriculum; and the ways in which they integrate media and technologies in their curriculum projects. Participants argued challenges and advantages of new media as classroom tools; developed skills in deconstructing existing curricula; examined the process of producing media for improving student outcomes; and they gained alternative points of view on educational media and renewed interest and commitment to new media literacies. Educators at all levels can use Digital Storytelling in many ways, from introducing new material to helping students learn to conduct research, synthesize large amounts of content and gain expertise in the use of digital communication and authoring tools. It also can help students organize these ideas as they learn to create stories for an audience, and present their ideas and knowledge in a meaningful way. This study follows the process of digital storytelling among undergraduates and explores three key topics in order to understand the educational experiences of the participants: the wide range of meanings participants associate with multimedia production and media education; the impact of media production activities in the curriculum; and the ways in which they integrate media and technologies in their curriculum projects. Participants argued challenges and advantages of new media as classroom tools; developed skills in deconstructing existing curricula; examined the process of producing media for improving student outcomes; and they gained alternative points of view on educational media and renewed interest and commitment to new media literacies. This presentation will discusses the role of developing innovative interdisciplinary introduction to Asian Studies course and integrating global literacies and new technologies as a means of further developing the 21st century skills among undergraduate students. Purpose This paper is for educators who would like to integrate global education, 21 st Century teaching skills (http://www.p21.org/) and digital storytelling into their curriculum. It outlines innovative multilingual and multicultural multimedia projects using mobile devices in teacher education; offers creative strategies for producing media with youth and developing Web 2.0 projects integrating world languages and 21 st century skills; provides the results of participatory research project between among pre-service teachers; describes participants' reactions and experiences with new technologies and showcases the participants’ multimedia projects and digital stories. An outcome of this presentation will be an online platform (i.e. curriki, ning, wikipedia, voicethread) for conference participants to contribute, communicate and collaborate on this topic. The presentation slides and the online course outline will be posted on our social networking page. We will present their role in developing the innovative interdisciplinary introduction to Asian Studies course and integrating global literacies and new technologies as a means of further developing the 21st century skills among undergraduate students. Although media production is considered to be a time consuming, difficult, and expensive process, educators need to integrate media literacy and media production into their curriculum in order to prepare new generation for mediarich culture. Rather than just being technical or peripheral, media production must be simple and central to the learning process. Media Literacy was defined at the Aspen Institute in 1989 as “ability to access, analyze, communicate, and produce media in a variety of forms.” Media literacy is more than asking students to simply decode information that they experience in the media; they must be able to talk back and produce media. As Ernest L. Boyer said: "It is no longer enough simply to read and write. Students must also become literate in the understanding of visual images. Our children must learn how to spot a stereotype, isolate a social cliché, and distinguish facts from propaganda, analysis from banter, and important news from coverage." According to Kubey & Baker, “the educational establishment is still often mystified about how to retool and retrain to educate future citizens for the new realities of communication.” Although the Kubey-Baker report outlines unmistakable and hopeful signs of development in the area of media education, we actually find that only a few states included media production in their framework. The role of media production in media education has been an important topic of discussion among educators. With the help of new media and technologies, students will have more access and power to communicate and produce their own projects, presentations, and portfolios and share them with other students around the world. As Renee Hobbs states in her internet article “The Seven Great Debates of Media Literacy Movement,” there is controversy over whether media literacy can be learned solely by deconstructing videos or whether it is necessary for one to learn how to create the videos. Therefore from a deconstructionist perspective, media production is a waste of time in reaching Media Literacy goals. In addition to hardware and software problems and equipment needs, inflexible scheduling in the school create difficulty for media production. “Child-created video is often resisted by teachers. They feel that there is no time for it after all the other demands on the curriculum are met, but a closer look shows that video tape production need not compete with other activities.” (LeBaron, 1981) On the other hand, Adams and Hamm (p 32) encourages both the production and the analysis components of media education. They emphasize the importance of creating personal meaning from the visual and verbal symbols and to be able to produce in the media culture. (Adams & Hamm, 2000) If our goal is to prepare ourselves for the media -rich culture we live in, then we need to focus on learning how to identify the message and the audience in order to reach our goal -- to educate students. The participants in my research were encouraged to think that process rather than the product was important in media production exercises. In addition, the participants were required to work on Pre-Production stage including storyboarding, script writing which constitutes the main part of the exercise. Williams and Medoff said (p.235), “…focus of the production away from technical expertise and toward the message and its interpretation.” This research explores the strategies for integrating media literacy and media production into the curriculum, offers creative suggestions for producing video in the classroom with minimal resources and equipment, and describes educators' experiences with media production. The role of media production in media education has been an important topic of discussion among educators. Valmont lists some questions such as “Video (TV) is helping or hurting education?” and “How can students learn anything from planning or producing their own videos?” (Valmont 1995) On the other hand, Buckingham argues the important role of media production in order to provide a means for students to explore and reflect their changing positions in contemporary media culture. He addresses the role of play, in relation to students’ media production. Through media production, students can develop a metalanguage, a form of critical discourse in which they construct and present their own interpretation of the world (Buckingham 2003). Adams and Hamm (p 32) encourage both the production and the analysis components of media education. They emphasize the importance of creating personal meaning from the visual and verbal symbols and being able to produce in the media culture (Adams & Hamm, 2000). Using video technologies activates the senses and symbolic thought, further developing one's intellectual abilities (Bruner, 1986). So instead of passive learners who read and analyze media texts and production, Potter stresses the importance of providing media tools to students so that they can produce their own media [video production]” (Potter, 1998). The Study This research project was conducted with 13 undergraduate students and 9 college teachers for co-teaching an undergraduate course. The goal was to examine how these educators integrate new media technologies and media literacy into the curriculum. Media Literacy is more than asking students to simply decode information that they experience with the media, they must be able to articulate and produce media. That is, a media literate person must be able to both decode (read) and construct (write) media. This research promotes literacy through media production in higher education, describes undergraduate students' reactions, discoveries, and experiences with media, and showcases their multimedia projects. It is based on the participatory research conducted on teaching media production classes and investigated their digital stories in their e-portfolios using content analysis methodology. The study explores the ways in which new media and technologies strengthen programs and build their capacity to prepare educators who can teach every student effectively. This study describes the video production experiences of college instructors who wanted to integrate video production and media literacy skills in the curriculum. In this study, by engaging in media production activities using camcorders and digital video editing software, participants experienced the power of technology and the unique characteristics of media production in their classroom. Some of the research questions in the study was 1. AUDIENCE-What are the participants’ personal experiences in media production? 2. PROBLEMS- What common problems do the participants share in their media production activities? 3. SUGGESTIONS- What suggestions do participants make in order to improve teaching and learning about media through production? 4. MEDIA LITERACY- What does it mean to be a media literate person living in a media rich culture? 5. DESIGN- How to design effective instruction integrating media production? The qualitative research process was used to investigate participants’ experiences in the area of media production. Methodology also included analysis of the media survey, questionnaires, electronic journals in online discussion forum, field notes derived from on-site classroom observations, video production exercises, and midterm and final projects. The research seeks to find out why teachers do not use media production in their teaching; and what kind of courses, institutes, or professional development projects need to be developed to support educators who would like to integrate media production into their teaching. Before the course, participants received an electronic media survey to fill out. The survey was designed to determine participants’ interest, background and experience in media education and media production. Most of the participants mentioned the power of the language and grammar exercise, which was presented in the first part of the course. It was introduction to language and grammar of media exercise. The students learned the basic media production techniques and conventions in this exercise.Through various activities and exercises, participants were exposed to various elements, techniques, and conventions of media. Participants’ responses to these activities were recorded as field notes after each class day in their online portfolios. They were organized under themes and topics and listed in a spreadsheet document to facilitate analysis of participants’ responses. Class exercises and projects, and research instruments were also studied. During the data analysis, it was difficult to establish measures that were reliable, valid, and that fit authentically with the course being presented. It was much easier to measure factual knowledge than it was to measure critical thinking skills and understanding of media techniques and conventions. In order to gain better understanding of the research questions, observation of group discussions during the class activities and reflection papers after each weekend -in addition to electronic journals and online discussion --were included in the study. To continue discussions online, a Blackboard.com course account was provided to each participant. It was used as a platform to post participants’ e-journals and homework assignments, to share ideas, and to generate questions and ideas. Electronic mail correspondence among the class members and with the instructor were also employed as content analysis materials. Participants’ homework, midterm and final projects were studied as an archival and secondary research material. The Findings To date, few scholarly studies have investigated either the power of documentary storytelling in the higher education classroom or the impact of media production on global education. This study addressed the gap by outlining the natural links between global education and media production. Undergraduate students researched, produced, and presented their digital projects such as video documentaries reflecting not only on their stories but also international issues and perspectives through their online contact to global community. Undergraduates argued the challenges and advantages of integrating media production into curriculum; developed skills in deconstructing existing curricula and digital resources and media messages; examined the process of integrating new media as a tool for teaching and learning; integrated the use of media in an instructional context in order to develop global understanding; explored lesson plans, assessment tools, and curriculum guides that incorporate new media and technologies across grades and subjects; experienced how a critical approach to the study of new media combines knowledge, reflection, and action to promote educational equity, and prepares new generation to be socially responsible members of a multicultural, democratic society. Participants enjoyed creating media projects and also gained media literacy skills. A number of students said they learned more than the video production. One participant said, “I am happy to have met you, because you have given me much more to think about than just the content of this class.” Another one wrote, “More than learning video production, this course gave me chance to reflect on my own viewing habits and learned something about myself.” They found the media literacy exercises and the resources were helpful in understanding media messages and its unique characteristics. Camera production was highly motivational indeed because the participants enjoyed working in creative ways to use the camcorders. The participants repeatedly said in their reflection papers how much they enjoyed working with the camera. As one said, “I don’t believe what you see on television. All these statements are untrue, after recently producing a commercial, I believe anything is visually possible with the help of fancy equipment.” Participants created lesson plans integrating video production into the curriculum, focused on lesson plans deconstructing ads, newspaper analysis. Participants who solely worked on digital editing did not see the importance of video production in the classroom. They pointed out they prefer using the ready-made videos to use in the classroom. As one participant said “I wish I could take the time to develop a video but I know I would get frustrated and end up just looking for a video already made to fit into my unit” And added “It is better to deconstruct, constructing takes so much time and frustrating.” 'The camera never lies', 'seeing is believing,' and 'what you see is what you get' were accepted expressions. However, what we see on TV, or hear on the radio are constructions and they reflect the producers', authors', and camerapersons’ and journalists' point of view. By actively involving participants in producing media such as PSA (public service announcement), they understood the conventions of the medium. As they became the producers of their own media projects, they developed media literacy skills, and became informed consumers and citizen of the world. Through the discovery process, undergraduates designed, and created the strategies, curricula, and programs for improving their students’ learning outcomes. They also gained alternative points of view on historical events as well as renewed interest and commitment to multiculturalism. Format The format of this presentation will include showcasing undergraduates’ selected video projects, interactive group discussions, and deconstruction exercises evaluating educational media resources, and a discussion of the research findings, and creating a mini-book based on the exercise called. The research paper and the results of our participatory research will be provided as a handout. The slide presentation and the online course outline will be posted on the weblog as a reference and future collaboration with conference participants. Participants will be able to: • • argue the challenges and advantages of integrating media production into the interdisciplinary and collaborative course design, • • develop skills in deconstructing existing curricula and digital resources and communicating media messages; • • examine the process of preparing project based learning activities for an interdisciplinary teaching and learning, • • integrate the use of media in an instructional context in order to develop global understanding; • • explore lesson plans, assessment tools, curriculum guides and links to online resources and students' projects. • • experience how a critical approach to the study of new media combines knowledge, reflection, and action to promote educational equity, • • create their own mini-book which includes online resources and activities for integrating media education into the curriculum. Overview of the presentation This session will benefit higher education faculty, teacher educators and students, parents, media specialists, and administrators who seek alternative strategies and tools in teaching and learning about Asia and Asian Culture and develop innovative interdisciplinary curriculum focusing on project based learning. The presentation slides, online course outline, online resources, and bibliography of recent literature as well as our students' multimedia projects will be made available to participant on our social networking site for further dialog and collaboration. Our online course model is at https://sites.google.com/a/kean.edu/as2000 Our slides will be posted on http://myildiz.weebly.com/presentations.html Our students Portfolios will be at http://ukean.wikispaces.com/E-portfolios References Adams, D., Hamm, M. (2000). Media and literacy: learning in an electronic age – issues, ideas, and teaching strategies. Charles C Thomas Publisher, Ltd. Springfield, Illinois. Bruner, J. (1986). Actual Minds, Possible Worlds. Cambridge, MA. Harvard University Press. Buckingham, D. (fall 2003). Media education and the end of the critical consumer. Harvard educational review, 73 (3). Hobbs, R. (1998). The seven great debates in the media literacy movement. Journal of Communication, 48(1):1632. Lebaron, F. J. (1981). Making Television: a video production guide for teachers. NewYork: Teachers College/ Columbia. Potter, W. J. (1998). Media literacy. London, New Delhi: Sage Publications. Valmont, W. J. (1995). Creating Videos for School Use. Needham Heights, MA. Allyn and Bacon. Williams, S. H., Medoff N. J. (1997). Production. In W. G. Christ (Ed.), Media education assessment handbook. (pp. 235-254). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers Mahwah, NJ