15.4 Rotational modes of diatomic molecules

advertisement

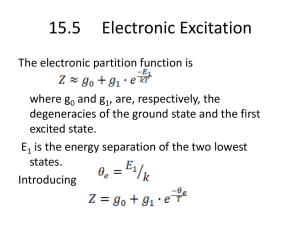

15.4 Rotational modes of diatomic molecules The moment of inertia, where μ is the reduced mass r0 is the equilibrium value of the distance between the nuclei. From quantum mechanics, the allowed angular momentum states are where l = 0, 1, 2, 3… … From classical mechanics, the rotational energy equals with w is angular velocity. The angular momentum therefore, the energy Define a characteristic temperature for rotation θrot can be found from infrared spectroscopy experiments, in which the energies required to excite the molecules to higher rotational states are measured. Different from vibrational motion, the energy levels of the above equation are degenerate. for level Now, one can get the partition function For , virtually all the molecules are in the few lowest rotational states. As a result, the series of can be truncated with negligible errors after the first two or three terms! For all diatomic gases, except hydrogen, the rotational characteristics temperature is of the order of 10 k (Kelvin degree). At ordinary temperature, Therefore, a great many closely spaced energy states are excited. The sum of may be replaced by an integral. Define: Note that the above result is too large for homonuclear molecules such as H2, O2 and N2 by a factor of 2… why? The slight modification has no effect on the thermodynamics properties of the system such as the internal energy and the heat capacity! Using ln Z U NkT T V 2 U CV , rot Nk T v At low temperature Keeping the first two terms (Note: again ) Using the relationship 2 ln Z 2 U NkT NkT 3 e T V 2 rot T rot 2 2 T (for And U CV ,rot 6 Nk rote T V 2 ro t T ) rot 2 2 T (for ) Characteristic Temperatures Characteristic temperature of vibration of diatomic molecules Substance θvib(K) H2 6140 O2 2239 N2 3352 HCl 4150 CO 3080 NO 2690 Cl2 810 Characteristic temperature of rotation of diatomic molecules Substance θrot(K) H2 85.4 O2 2.1 N2 2.9 HCl 15.2 CO 2.8 NO 2.4 Cl2 0.36 15.5 Electronic Excitation The electronic partition function is where g0 and g1, are, respectively, the degeneracies of the ground state and the first excited state. E1 is the energy separation of the two lowest states. Introducing For most gases, the higher electronic states are not excited (θe ~ 120, 000k for hydrogen). therefore, ln Z U NkT 0 T V 2 U CV 0 T V At practical temperature, electronic excitation makes no contribution to the external energy or heat capacity! 15.6 The total heat capacity For a diatomic molecule system Since Discussing the relationship of T and Cv (p. 288-289) Heat capacity for diatomic molecules • Example I (problem 15.7) Consider a diatomic gas near room temperature. Show that the entropy is 3 7 2mk 2 T 5 2 S Nk ln 2 , 2 h 2 rot • Solution: For diatomic molecules S S trans S vib S rot S excit At room temperature S excit 0 1 1 Nk e T T 2 e 1 Nk ln S vib 1 e T T 0 (does not contribute!) • For translational motion, the molecules are treated as non-distinguishable assemblies 3 U NkT 2 three degrees of freedom 3 2mkT 2 Z V 2 h U S tr Nk ln Z ln N 1 T 3 5 V 2mkT 2 S tr Nk Nk ln 2 2 N h • For rotational motion (they are distinguishable in terms of kinetic energy) U NkT Z 1 due to homonuclea r molecule 2 T 2 rot U NkT ln Z for distinguis hable assembly T T Nk Nk ln 2 rot S 5 V S system Nk Nk ln 2 N V 7 S system Nk Nk ln 2 N 2mkT 3 2 T Nk Nk ln h 2 2 rot 2mk 3 / 2 T 5 2 h 2 2 rot • Example II (problem 15-8) For a kilomole of nitrogen (N2) at standard temperature and pressure, compute (a) the internal energy U; (b) the Helmholtz function F; and (c) the entropy S. • Solution: calculate the characteristic temperature first! vib 3352k and r 2.9k for N 2 U U trans U vib U rot 1 3 1 NkT U NkT Nk vib 2 2 e T 1 because r T U 1 5 1 NkT Nk vib 3352 2 2 e 298 1 1 3352 Nk 2.5 298 3352 11.25 2 e 1 3352 Nk 2272 11.25 e 1 1.0kmol 8.314 103 J kmol1 k 1 2272 1.89 10 7 J F NkT ln Z ln N 1 non distinguis hable particles F NkT ln Z Distinguis hable particles such as vib & rotation Ft NkT ln Z t ln N 1 2mkT Zt V 2 h 3 2 2 4.65 10 1.38110 22.4m 2 68 6 . 626 10 26 3 22.427.3 10 22.4 273.86 10 19 3 2 20 3 23 Jk 298 1 3 2 2 3 2 3.195 1033 3.195 1033 6 Ft NkT ln 1 NkT ln 5 . 15 10 1 26 6.02 10 NkT 16.4 Fvib NkT ln Z vib Z vib e 3352 1 e 2298 3352 298 e 5.62 1 e 11.24 1 ln Z vib 5.62 ln 1 11.24 5.62 e T Fvib NkT ln Z rot Z rot for T rot rot 298 102.72 ln Z rot 4.63 2.9 Frot 4.63 NkT Z rot F Frot Fvib Ft 4.63 NkT 5.62 NkT 16.4 NkT 15.41NkT 15.41 6.02 10 26 1.38 10 23 298 3.817 107 J