Slide 1 - UNM Biology

advertisement

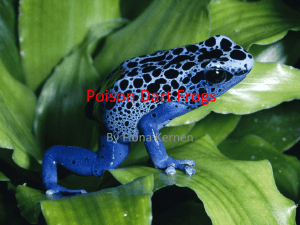

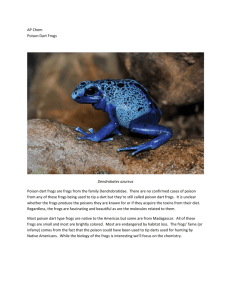

Presented By: Lyric Bowles Mizba Kesani Kisa King The Poison Dart Frog Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Amphibia Order: Anura Suborder: Neobatrachia Family: Dendrobatidae The Poison Dart Frog Habitat: native to the humid, tropical environments of Central and South America; found mostly in the rainforests of Columbia Temperature: 22 -27 oC (high) - 16-18 oC (low) Humidity: 80-100% Size: up to 2.5 inches Weight: up to 2 grams Life Span: Captivity: up to 25 years Wild: approximately 1-3 years Diet: small insects and other small invertebrates The Poison Dart Frog These frogs are brightly colored in aposmatic patterns to warn predators of their toxicity. Females compete for "nests" and males compete for the best spot from which to broadcast their mating calls Females often lay their eggs on the forest floor or on leaves. Adult frogs produce mucous which functions as a “glue” and allows tadpoles to be transported to an aquatic environment on the backs of their parents. While in the water, tadpoles diet consists of small invertebrates; however, the mother is known to deposit eggs into the water in order to supplement the tadpole's diet. The Poison Dart Frog Some species, three in particular, are extremely toxic to humans. The most poisonous of the three is the golden poison dart frog (Phyllobates terribilis). A single golden poison dart frog can kill between 10-20 people (or other large mammals); this is equivalent to approximately 10,000 mice! Local indigenous tribes of Central and South America use the toxin produced from P. terribilis in the darts which they use for hunting. Once on the dart, the toxins can keep its effect for over 2 years. The Golden Poison Dart Frog is currently thought to be the most poisonous vertebrate! Toxin Batrachotoxin (BTX) is the actual compound secreted by the poison dart frog. BTX was first discovered in the skin secretion of the Columbian poisonous dart frog in the 1960s. The structure of this toxin is shown to be a steroidal alkaloid. Studies have shown that this toxin is not produced by these frogs while in captivity. Therefore, it has been theorized that part of the toxin is produced by consumption of certain foods available to frogs. A study conducted in 2004 showed that this toxin comes from the consumption of choresine beetles by these frogs. However, choresine beetles also cannot produce parts of this toxin, so to do so, they eat different types of sterol producing plants. (Choresine bettle) Toxicity • BTX is a powerful neurotoxin with a low LD50 of 2 g/kg in mice and 1-2 micrograms/kg in humans. • The lethal dose for a 150 pound human is about 100 micrograms, which is equivalent to the weight of two grains of table salt! • BTX is fifteen times more poisonous than Curare (another arrow poison used by South American Indians; obtained from plants). • Batrachotoxin is ten times more poisonous than tetrodotoxin (toxin produced by puffer fish). • BTX also has dangerous affects on the heart similar to those of digitalis. Mechanism of Action Batrachotoxin works by changing the membrane potential of a cell. This results in the numbing of human muscular tissues. • The membrane potential is the voltage difference between the outside and inside of the cell (ion concentration between inside and outside of cell). • A normal cell has a higher concentration of potassium ions inside the cell and higher concentration of sodium outside the cell. • The ion concentration between the exterior and interior cell is maintained by ion channels and ion pumps. • How does batrochotoxin affect the membrane potential? Batrachotoxin binds to the voltage-gated sodium channel of the cell membrane. • This binding causes the sodium channel stay permanently open. The open conformation allows ions to freely pass through the membrane which changes the membrane potential. • The change in membrane potential and the loss of the sodium/potassium concentration gradient keeps nerve and muscle cells from transmitting electrical signals properly and from carrying on their natural functions. • This leads to paralysis and death, with death resulting from muscular and respiratory paralysis. • Treatment • This toxin can be can be treated with local anesthetics, anti-arrythimic drugs, anti-convulsants, and tetrodotoxin. • These treatments keep batrachotoxin from binding to the voltage-gated sodium ion channels. • Local anesthetics may act as receptor antagonists or as competitive antagonists, which block the action all together. • Tetrodotoxin is a noncompetitive inhibitor that binds to voltage-gated sodium ion channels (similar to batrachotoxin), but instead of permanently opening the channels, it closes them. Treatment There is currently no known antidote for batrachotoxin poisoning! Like veratridine, aconitine and grayanotoxin, batrachotoxin is a lipid-soluble poison which alters the ion selectivity of sodium channels. This suggests a similar site of action amongst these toxins. Based on this similarity, researchers are attempting to obtain a treatment for batrachotoxin poisoning by modeling it after treatment for these other poisons. As mentioned earlier, membrane depolarization caused by BTX can be prevented or reversed by either tetrodotoxin or saxitoxin, but this is not an antitode and side effects can be severe. Present/Future Medical Uses In recent years, researchers have found that poison dart frog batrochotoxins are actually 1000 times more effective than morphine at treating pain! More importantly, unlike morphine and other painkillers, there are no addictive properties associated with BTX. BTX could potentially become an active ingredient in painkiller ointments. In 1998, scientist were able to synthesize BTX in the laboratory and have done extensive research regarding structure and function of BTX, as well as, its interaction with voltage-gated sodium channels. The Bigger Picture Frogs have existed on Earth for more than 250 million years; surviving dinosaurs, asteroids and ice ages. Today, however, more than 1/3 of the all amphibian species are in decline and/or are on the verge of extinction. The main contributor to this decline is the invasion of Chytridiomycosis. (Frog population infected with Chytridiomycosis) The Bigger Picture Chytridiomycosis is a disease caused by an aquatic chytrid fungal pathogen known as Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (BD). Chytridiomycosis attacks the skin of frogs depriving them of oxygen and ultimately leads to death. Researchers have no idea where this pathogen originated or how to contain it once it arrives at a frog population. Why is this significant? The Bigger Picture Researchers have only begun to study the beneficial properties of secretions obtained from the skin of frogs. With populations in decline, there is no telling what medical discoveries will disappear with them! These little creatures could hold the key to solving numerous medical dilemmas and they could all be gone before we have a chance to utilize and understand them fully. Batrochotoxins are not the only toxin being researched for its medical uses. Chemicals secreted through the skin of frogs are being research for everything from treatment of infections to treatment of HIV. Take Home Message Batrachotoxin is a neurotoxin secreted through the skin of poison dart frogs. It is because of this toxin that the Golden Poison Dart Frog has been called the most poisonous vertebrate. Batrachotoxin works by permanently opening voltage-gated sodium channels that are essential to the proper functioning of the nervous system. Batrachotoxin has been used by several tribes for hunting purposes. It is being researched for its benefits in treating pain. There is no known antidote for batrachotoxin poisoning but treatments are available. Finally, with amphibian populations slipping away faster than scientists can study them, there is no telling what other medically significant toxins will go undiscovered. References Myers, C. W., J. W. Daly, and B. Malkin (1978). "A dangerously toxic new frog (Phyllobates) used by Embera Indians of western Colombia, with discussion of blowgun fabrication and dart poisoning". Bull. Amer. Mus. Nat. Hist. 161 (2): 307–366. Caldwell, J.P. (1996). "The evolution of myrmecophagy and its correlates in poison frogs (Family Dendrobatidae).". Journal of Zoology 240: 75–101. "AmphibiaWeb - Dendrobatidae". AmphibiaWeb. http://amphibiaweb.org/lists/Dendrobatidae.shtml. Retrieved 2010-0310 “Batrachotoxin”. http://chemweb.calpoly.edu/cbailey/377/PapersW08/PaulM/index.ht ml. Retrieved 2010-04-05 “Chytrid Fungus-What is chytridiomycosis?”. Chytrid Fungus. http://web.me.com/vancevredenburg/Vances_site/chytridiomycosis.ht ml Retrieved 2010-03-15 “Batrachotoxin” http://www.wou.edu/~hgrimes/ch350/. Retrieved 2010-03-10