evidence-based reading instruction

advertisement

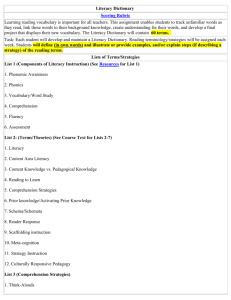

EVIDENCE-BASED READING INSTRUCTION: The Critical Role of Scientific Research in Teaching Children, Empowering Teachers, and Moving Beyond the “Either-Or Box” G. Reid Lyon, Ph.D. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development National Institutes of Health Lyonr@mail.nih.gov READING FAILURE: AN EDUCATIONAL AND A PUBLIC HEALTH PROBLEM Reading Proficiency is Critical to Academic Learning and Success in School (Lyon, 1998; 2002, 2003, 2004; Snow, Burns & Griffin, 1998) The Ability to Read Proficiently is Significantly Related to Quality of Life and Health Outcomes (Lyon, 1997; Lyon & Chhabra, 2004; Thompson, 2001) READING PROFICIENCY IN 2004 HOW ARE WE DOING IN THE UNITED STATES? DO MORE STUDENTS HAVE GREATER DIFFICULTIES LEARNING TO READ TODAY THAN: 10 YEARS AGO? 20 YEARS AGO? 30 YEARS AGO? Long Term Trends in Reading Achievement From the National Assessment of Educational Progress Right now, all over the United States, we are leaving too many children behind in reading And, a large share of those children come from poor and minority homes Percent of Students Performing Below Basic Level - 37% 10 White 20 30 40 50 60 70 27 Black 63 Hispanic 58 Poor 60 Non-poor 26 80 90 100 “Current difficulties in reading largely originate from rising demands for literacy, not from declining absolute levels of literacy” Report of the National Research Council MAJOR SOURCES OF READING FAILURE Socioeconomic Factors – Poverty Biological Factors – Genetics and Neurobiology Instructional Factors - Predominate SOME REASONS WHY READING INSTRUCTION HAS NOT BEEN HELPFUL Untested Theories and Assumptions Regarding Reading Development and Instruction Romantic Beliefs About Learning and Teaching Fads Appeals to “So Called” Authority Some Myths About Interventions for Struggling Readers Learning to Read is a Natural Process Children who Struggle to Learn To Read in the Early Grades Will “Catch Up” If You give Them Time Children are Either Auditory or Visual Learners and Should Be Taught to Read Accordingly Theories of “Multiple Intelligences” or “Learning Styles” Can Help Us Adapt Our Reading Instruction to the Needs of Different Children Quality Time With an Enthusiastic Volunteer Tutor Can Solve Most Children’s Reading Difficulties BUT, RISING NEEDS FOR HIGH LEVELS OF LITERACY… Demand That We Break the Mold of Past Performance!!! We Must Do Better Than Has Ever Been Done Before!!! THIS WIL NOT BE EASY!!!!!!!! What makes us think we can do better? We now have substantial converging scientific evidence about: • How children learn to read • Why some children have difficulty • How to prevent and remediate reading difficulties Federal funding for the prevention and remediation of reading failure has increased significantly What makes us think we can do better? There is an emphasis on accountability: We use assessments to tell us how well students are reading We use assessment data to inform instruction We have many examples of schools that beat the odds in reading achievement when valid assessments and evidencebased instruction are provided What makes us think we can do better? We are shifting from grounding educational practices and policies in political and philosophical contexts to basing instruction on the attitudes and values of science We are relying on scientific criteria for the evaluation of knowledge claims: Peer Reviewed Publication Replication (Convergence) Scientific Consensus Scientific Research A process of rigorous reasoning based on interactions among theories methods, and findings; Builds on understanding derived from the objective testing of models or theories; Accumulation of scientific knowledge is laborious, plodding, and indirect; Scientific knowledge is developed and honed through critique contested findings, replication, and convergence; Scientific knowledge is developed through sustained efforts; Scientific inquiry must be guided by fundamental principles. Reading Research is Not an Either-Or Proposition THE SCIENTIFIC QUALITY OF A STUDY HAS NOTHING TO DO WITH WHETHER IT EMPLOYS QUANTITATIVE OR QUALITATIVE DESIGNS AND METHODS A QUALITY RESEARCH PROGRAM REFLECTS A DIMENSION OF INQUIRY FROM DESCRIPTION THROUGH CONFIRMATION Reading Research is Not an Either-Or Proposition Designs and methods are selected to permit direct investigation of the question The trustworthiness of any study is predicated on: The appropriateness of the design and methods to address the specific questions The scientific rigor with which the design and method are applied Reading Research is Not an Either-Or Proposition The Majority of NICHD Supported Studies Include BOTH Quantitative and Qualitative Designs and Methods An Examination of the Social and Cultural Influences on Adolescent Literacy Development Elizabeth Birr Moje Jacquelynne Eccles Pamela Davis-Kean Helen Watt Paul Richardson University of Michigan Assessments Interviews Observation Literacy Skills in Context Surveys Interviews Diary Studies Observation Motivations & Expectancies Examination of Social and Cultural Influences on Adolescent Literacy Development Out-of-School Engagements Observation Interviews Textual Analyses Assessments Transfer Across Contexts Observation Interviews Experimental Tasks Summary of Scientific Criteria A study is deemed to be “scientific” when: There are a clear set of testable questions underlying the design; The methods are appropriate to answer the questions and falsify competing hypotheses and answers; The study is explicitly linked to theory and previous research; The data are analyzed systematically and with the appropriate tools; The data are made available for review and criticism. HOW WAS THE SCIENTIFIC EVIDENCE OBTAINED AND UNDER WHAT CONDITIONS? A Commitment to Focus on Four Research Questions: How Do Children Learn to Read? Why Do Some Children Have Difficulties Learning To Read? How Can Reading Failure Be Prevented? How Can Persistent Reading Difficulties be Remediated? THE NICHD SCIENTIFIC INVESTMENT in READING – K-6 Number of Research Sites: Children and Adults Studied: Proficient Readers: At-Risk/Struggling Readers Average Years Studied/Followed: Max Longitudinal Span to Date: Current Prevention/Intervention Trials Schools Currently Participating: Classrooms Currently Participating: Classroom Teachers Participating: Annual Research Budget: 44 48,000 22,000 26,000 9 22 12 266 985 1,012 $ 60 Million NICHD Reading Research Program University of Washington Berninger Boy’s Town Smith Loyola Univ/Chicago Morrison Mayo Clinic Kalusic Univ of Massachusetts Syracuse Univ Rayner Blachman Tufts Wolf Toronto Lovett SUNY Albany Vellutino San Luis Ebispo Lindamood/Bell Emerson Coll Aram Beth Israel Galaburda Yale Univ Shaywitz Univ of Southern California Manis/Seidenberg Haskins Labs Fowler/Liberman Johns Hopkins Denckla UC Irvine Filipek Univ of California --San Diego, Salk Institute Bellugi Children’s Hospital/ Harvard LDRC Waber D.C./Houston Foorman/Moats Georgetown Univ Eden U of Houston Francis Colorado LDRC Defries Bowman Gray Wood Georgia State R. Morris Yale Methodology Fletcher Univ of Texas Med Ctr Foorman/Fletcher NICHD Sites Florida State Torgesen/Wagner Univ of Missouri Southern Illinois U Geary Moltese Univ of Arkansas-Med Ctr Dykman Univ of Georgia Hynd U of Florida Alexander/Conway The NICHD/OSERS/OVAE Scientific Investment Grades 7-12 Adolescent Literacy Network Funded in 2004, will study >12,700 students across five projects Elizabeth Birr Moje: University of Michigan – Social and Cultural Influences on Adolescent Development and Literacy Bennett Shaywitz: Yale University – Adolescent Literacy: Classification, Mechanism, and Outcomes James McPartland: Johns Hopkins University – Supporting Teachers to Close Adolescent Literacy Gaps Laurie Cutting: Kennedy Krieger Institute – Cognitive and Neural Process in Reading Comprehension Hollis Scarborough: Haskins Labs – Adolescent Reading Programs : Behavioral and Neural Effects The NICHD/IES Scientific Investment: English Language Learners 80 Research Sites in 12 States, Mexico, and Puerto Rico Children Studied: ~ 9,000 Scientific Investment: ~ $32 Million Dollars over five years Dr. David Francis: University of Houston Dr. Diane August: Center for Applied Linguistics Dr. Carol Hammer: Pennsylvania State University Dr. Mark Innocenti: Utah State University Dr. Kim Lindsey: University of Southern California Dr. Alexandra Gottarda: Grand Valley State University The NICHD/NIFL/OVAE Scientific Investment Adult Literacy Network 80 Research Sites in 16 States Adults to be screened: 73,000 Adults to be studied: > 3,800 Scientific Investment: > $18.5 Million Dollars over five years Daphne Greenberg: Georgia State University, Research on Reading Instruction for Low Literate Adults Susan Levy: University of Illinois, Testing Impact of Health Literacy in Adult Literacy and Integrated Family Approach Programs Daryl Mellard: University of Kansas – Lawrence, Improving Literacy Instruction for Adults John Sabatini: Educational Testing Services, Relative Effectiveness of Reading Programs for Adults Frank Wood: Wake Forest University of the Health Sciences, Young Adult Literacy Problems: Prevalence and Treatment Richard Venezky: University of Delaware, Building a Knowledge Base for Teaching Adult Decoding The NICHD/OSEP/HHS Scientific Investment: Early Childhood and School Readiness WHICH EARLY CHILDHOOD PROGRAMS OR PROGRAM COMPONENTS ALONG WITH INTERACTIONS WITH ADULTS AND PEERS ARE EFFECTIVE FOR PROMOTING EARLY LEARNING AND DEVELOPMENT: FOR WHICH CHILDREN UNDER WHAT CONDITIONS The NICHD/OSEP/HHS Scientific Investment: Early Childhood and School Readiness Network Annual Research Budget: $7.5 Million Dr. Karen Berman: Penn State U. Dr. John Fantuzzo: U. Pennsylvania Dr. Carollee Howes: UCLA Dr. Janis Kupersmidt: UNC-Chapel Hill Dr. Samuel Odom: Indiana U. Dr. Robert Pianta: U. of Virginia Dr. Cybelle Raver: U. of Chicago Dr. Susan Sheridan: U. of Nebraska HOW DO CHILDREN LEARN TO READ? Critical Language and Literacy Interactions from Birth Onward Phonemic Awareness Phonics Fluency Vocabulary Reading Comprehension Strategies HOW DO CHILDREN LEARN TO READ? EARLY LANGUAGE AND LITERACY INTERACTIONS Language Hart and Risley (1995) conducted a longitudinal study of children and families from three groups: Professional families Working-class families Families on welfare Interactions Hart & Risley compared the mean number of interactions initiated per hour in each of the three groups. 50 40 30 20 10 0 Welfare Working Professional Interactions Hart & Risley also compared the mean number of minutes of interaction per hour in the three groups. 50 40 30 20 10 0 Welfare Working Professional Differences in exposure to words over the course of one year Children in Professional Families -- 11 million Children in Working-Class Families -- 6 million Children in Welfare Families -- 3 million Cumulative Language Experiences Cumulative Words Spoken to Child (in millions) 50 40 30 Professional Working 20 Welfare 10 0 0 12 24 Age of child (in months) 36 48 The Effects of Weaknesses in Oral Language on Reading Growth (Hirsch, 1996) 16 High Oral Language in Kindergarten 15 14 5.2 years difference Reading Age Level 13 12 11 Low Oral Language in Kindergarten 10 9 8 7 6 5 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Chronological Age 14 15 16 HOW DO CHILDREN LEARN TO READ ? PHONEMIC AWARENESS What is Phonological Awareness? Phonological awareness involves the understanding that spoken words are composed of segments of sound smaller than a syllable. It also involves the ability to notice, think about, or manipulate the individual sounds in words. Why is phonological awareness important in learning to read? It helps children understand the alphabetic principle Children must understand that the words in their oral language are composed of small segments of sound in order to comprehend the way that language is represented by print. Without at least emergent levels of phonemic awareness, the rationale for learning individual letter sounds, and “sounding out” words is not understandable. Growth in “phonics” ability of children who begin first grade in the bottom 20% in Phoneme Awareness and Letter Knowledge (Torgesen & Mathes, 2000) 6 Reading Grade Level 5 4 5.9 Low PA Low Ave. PA Average 3 2.3 2 1 K 1 2 3 4 Grade level corresponding to age 5 Growth in word reading ability of children who begin first grade in the bottom 20% in Phoneme Awareness and Letter Knowledge (Torgesen & Mathes, 2000) 6 Low PA Low Average Ave. PA 5 Reading grade level 5.7 4 3.5 3 2 1 K 1 2 3 4 Grade level corresponding to age 5 Growth in reading comprehension of children who begin first grade in the bottom 20% in Phoneme Awareness and Letter Knowledge (Torgesen & Mathes, 2000) 6.9 Reading Grade Level 6 5 Low Average 4 3.4 3 2 Same verbal ability – Low PA very different Reading Ave. PA Comprehension 1 K 1 2 3 4 Grade level corresponding to age 5 Mean Effect Sizes Produced by Phonemic Awareness Instruction on Reading Outcomes (Ehri, 2004) Characteristics Of Reading Outcomes Phonemic Awareness Word Reading Pseudo Word Reading Spelling Comprehension Math Effect Size .86* .46* .52* .59* .34* .15 HOW DO CHILDREN LEARN TO READ? PHONICS (PHONEMIC DECODING ) What is “Phonics”? It is a kind of knowledge Which letters are used to represent which phonemes It is a kind of skill Pronounce this word… blit fratchet Connecticut Longitudinal Study (Shaywitz et al.) The next slide shows correlations over time between the Woodcock Reading Mastery Test Passage Comprehension Scores and WRMT Decoding composite (Letter Word and Word Attack) scores The CLS sample is an epidemiologic sample from Connecticut, largely white, middle to upper income children (Shaywitz, et al., 1990) with very low attrition (over 90% retention through Grade 9) Correlation between Decoding and Comprehension on the Woodcock-Johnson from Grades 1-9 (N=395) Comprehension Grade Decoding Grade 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 .89 .75 .70 .64 .58 .59 .53 .49 .52 .79 .83 .74 .71 .63 .65 .61 .58 .58 .73 .78 .77 .74 .68 .67 .65 .62 .60 .69 .74 .74 .73 .67 .68 .65 .62 .62 .64 .70 .71 .70 .70 .67 .68 .64 .60 .66 .70 .75 .74 .69 .69 .69 .65 .63 .66 .71 .72 .72 .67 .67 .69 .65 .63 .61 .68 .72 .68 .66 .66 .66 .63 .61 .65 .69 .71 .70 .66 .66 .68 .63 .63 Early Interventions Sample (Foorman, et al.) The following slide shows correlations for two measures of comprehension, WJ PC and the CRAB (Fuchs & Fuchs), with two measures of decoding over four years in a freshened longitudinal sample recruited from 17 high poverty schools in two cities. The sample was over 95% African American. Children were randomly sampled from Kindergarten and Grade 1 classrooms and followed longitudinally through Grade 4. Correlations for WJ PC and CRAB with three Decoding Measures from Grades 1 to 4 for Ethnic-minority Children Grade 1 Grade 2 Grade 3 Grade 4 PREDICTOR PC_W CRAB PC_W CRAB PC_W CRAB PC_W CRAB WJ LETTER WORD W SCORE 0.7399 <.0001 1432 0.769 0.7910 5 <.0001 <.000 1086 1 504 0.716 0.7685 64 4 <.000 <.0001 1 1063 1044 0.650 0.7541 53 2 <.000 <.0001 1 712 1042 0.666 56 <.000 1 706 WJ WORD ATTACK W SCORE 0.7044 2 <.0001 1423 0.621 0.3917 99 0 <.000 <.0001 1 1089 504 0.316 0.2402 29 5 <.000 <.0001 1 1063 1049 0.248 0.6414 92 2 <.000 <.0001 1 712 1042 0.597 55 <.000 1 706 Mean Effect Sizes Produced by Systematic Phonics Instruction Characteristics Of Reading Outcomes Effect Sizes Kindergarten and First Graders Decoding Regular Words Decoding pseudowords Reading Miscellaneous Words Spelling Words Reading Text Orally Comprehending Text .98* .67* .45* .67* .23* .51* Mean Effect Sizes Produced By Systematic Phonics Instruction Characteristics Of Reading Outcomes Effect Sizes Second Through Sixth Grade Decoding Regular Words Decoding Pseudowords Reading Miscellaneous Words Spelling Words Reading Text Orally Comprehending Text .49* .52* .33* .09 .24* .12 HOW DO CHILDREN LEARN TO READ? READING FLUENCY A common definition of reading fluency: “Fluency is the ability to read text quickly, accurately, and with proper expression.” National Reading Panel The most common method of measuring reading fluency in the early elementary grades: Measuring the number of accurate words per minute a child can read orally The challenge of continuing growth in fluency becomes even greater after third grade 4th, 5th, and 6th graders encounter about 10,000 words they have never seen before in print during a year’s worth of reading Furthermore, each of these “new” words occurs only about 10 times in a year’s worth of reading Sadly, its very difficult to correctly guess the identity of these “new words” just from the context of the passage HOW DO CHILDREN LEARN TO READ? VOCABULARY Relationship between Vocabulary Score (PPVT) measures in Kindergarten and later reading comprehension End of Grade One -- .45 End of Grade Four -- .62 End of Grade Seven -- .69 The relationship of vocabulary to reading comprehension gets stronger as reading material becomes more complex and the vocabulary becomes becomes more extensive (Snow, 2002) Bringing Words to Life Isabel Beck M. McKeown L. Kucan Guilford Press Big ideas from “Bringing Words to Life” First-grade children from higher SES groups know about twice as many words as lower SES children. Poor children, who enter school with vocabulary deficiencies have a particularly difficult time learning words from “context.” Research has discovered much more powerful ways of teaching vocabulary than are typically used in classrooms. A “robust” approach to vocabulary instruction involves directly explaining the meanings of words along with thought-provoking, playful, interactive follow-up. What we haven’t yet demonstrated we know how to do Close the “vocabulary gap” between low SES and higher SES children This gap arises because of massive differences in opportunities to learn “school vocabulary” in the home. HOW DO CHILDREN LEARN TO READ? COMPREHENSION Some definitions of reading comprehension to make a point about remaining gaps in our knowledge “Acquiring meaning from written text” Gambrell, Block, and Pressley, 2002 “the process of extracting and constructing meaning through interaction and involvement with written language” Sweet and Snow, 2002 “thinking guided by print” Perfetti, 1985 Preparing children to meet grade level standards in reading comprehension by the end of third grade is as much about providing the vocabulary and thinking skills they need as it is about helping them learn to read accurately and fluently This point becomes increasingly important as we move up the grades What we know about the factors that affect reading comprehension Proficient comprehension of text is influenced by: Accurate and fluent word reading skills Oral language skills (vocabulary, linguistic comprehension) Extent of conceptual and factual knowledge Knowledge and skill in use of cognitive strategies to improve comprehension or repair it when it breaks down. Reasoning and inferential skills Motivation to understand and interest in task and materials •Life Experience •Content Knowledge •Activation of Prior Knowledge •Knowledge about Texts Knowledge •Motivation & Engagement •Active Reading Strategies •Monitoring Strategies •Fix-Up Strategies Language Reading Comprehension Metacognition •Oral Language Skills •Knowledge of Language Structures •Vocabulary •Cultural Influences Fluency •Prosody •Automaticity/Rate •Accuracy •Decoding •Phonemic Awareness Why the disparity between early wordlevel outcomes and later comprehension of complex texts? Demands of vocabulary in complex text at third grade and higher place stress on the remaining SES related “vocabulary gap” More complex text demands reading comprehension strategies and higher level thinking and reasoning skills that remain “deficient” in many children A big idea to keep in mind: Preparing children to meet grade level standards in reading comprehension by the end of third grade and beyond is a job for all teachers, not just “reading teachers” and special educators. It’s at least as much about building content knowledge, vocabulary, and thinking skills as it is about helping children learn to read accurately and fluently WHAT DOES THE RESEARCH SAY ABOUT INSTRUCTION? CRITICAL ELEMENTS 5 + ii + 3 + iii = NCLB Five Instructional Components: Phonemic Awareness Phonics Identifying words accurately and fluently Fluency Vocabulary Comprehension strategies Constructing meaning once words are identified “High quality initial instruction in the classroom is the first line of defense against reading difficulties” NRC report, 1999 “The characteristics of a good program are that it contains the five elements identified in the legislation, and that these elements are integrated into a coherent instructional design. A coherent design includes explicit instructional strategies, coordinated instructional sequences, ample practice opportunities and aligned student materials.” HOW ARE WE DOING? SPECIAL EDUCATION PLACEMENT EARLY INTERVENTION EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICES IN SCHOOLS 120 100 80 60 40 70 71.8 20 G ra de 6 G ra de 5 G ra de 4 0 G ra de 3 Standard Score in Reading Change in Reading Skill for Children with Reading Disabilities who Experience Growth in Reading of .04 Standard Deviations a Year Grade Level Average Readers Disabled Readers HOW CAN WE PREVENT READING FAILURE? Development of Sensitive and Valid Screening Measures Professional Development and Use of a Professional Common Language Implementation of Three-Tier Models Continuous Assessment of Progress Appreciation of School Leadership and Capacity Factors We do not yet know how to prevent reading difficulties in “all” children Percent of children scoring below the 30th percentile Author Type Before After Foorman 174 hrs. – classroom 35% 6% Felton 340 hrs. – groups of 8 32% 5% Vellutino 35-65 hrs. 1:1 tutoring 46% 7% Torgesen 88 hrs. 1:1 tutoring 30% 4% Torgesen 80 hrs. 1:3 tutoring 11% 2% Torgesen 91 hrs. 1:3 or 1:5 tutoring 8% 1.6% Mathes 80 hrs. 1:3 tutoring .02% 1% Standard Score Growth in Total Reading Skill Before, During, and Following Intensive Intervention 95 90 85 LIPS 80 EP 75 P-Pretest Pre Post 1 year 2 year Interval in Months Between Measurements Outcomes from 67.5 Hours of Intensive LIPS Intervention 100 96 91 30% 89 90 86 80 83 75 74 70 73 68 Word Attack Text Reading Accuracy Reading Comp. 71 Text Reading Rate Why are so many children currently being left behind? 1. Many elementary schools are not organized or focused in ways that most effectively promote literacy in all children. 2. Teachers often do not possess the special knowledge or teaching skill to effectively teach children who experience difficulties learning to read. 3. Many families and neighborhood environments do not provide experiences that prepare children to learn to read well. 4. There is significant variability in the language-based talents required for learning to read. 5. Many schools do not really expect children from low wealth or minority backgrounds to learn to read well. 6. Teachers often do not have adequate materials or instructional time available to them to effectively promote literacy in all their children. Evidence from one school that we can do substantially better than ever before School Characteristics: 70% Free and Reduced Lunch (going up each year) 65% minority (mostly African-American) Elements of Curriculum Change: Movement to a comprehensive reading curriculum beginning in 1994-1995 school year (incomplete implementation) for K-2 Improved implementation in 1995-1996 Implementation in Fall of 1996 of screening and more intensive small group instruction for at-risk students Hartsfield Elementary Progress over five years Proportion falling below the 25th percentile in word reading ability at the end of first grade 30 20 Screening at beginning of first grade, with extra instruction for those in bottom 30-40% 31.8 20.4 10.9 10 6.7 3.7 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 Average Percentile for entire grade (n=105) 48.9 55.2 61.4 73.5 81.7 The consensus view of most important instructional features for interventions Interventions are more effective when they: Provide systematic and explicit instruction on whatever component skills are deficient: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, reading comprehension strategies Provide a significant increase in intensity of instruction Provide ample opportunities for guided practice of new skills Provide systematic cueing of appropriate strategies in context Provide appropriate levels of scaffolding as children learn to apply new skills Reading stimulates general cognitive growth— particularly verbal skills Meanwhile, Back in the Brain Kindergarten S#1 S#31 At Risk Reader Left Kindergarten First Grade Right One Year After Intervention Right R L 1 Left 1 Z=+12 2 6 Z=-4 7 3 5 4 Shaywitz et al., Biol. Psychiatry, 2004